A monitoring committee released a report about the CIA’s use of torture in its secret prison network. But the United States still refuses to adhere to international torture-prevention mechanisms — a crucial first step to formulating a credible torture prevention policy. By Mark Thomson, secretary general of the Association for the Prevention of Torture in Geneva.

In 1973, when CIA director James Schlesinger told the president of the Senate Armed Services Committee, John Stennis, that he wanted to inform him about an upcoming major operation, the senator famously replied: “No, no my boy. Don’t tell me. Just go ahead and do it, but I don’t want to know.” Two years and several scandals later, the United States finally created a series of monitoring committees. One of these, the Senate Intelligence Committee, has now found itself in a difficult situation after it published a summary of its report on the use of torture in the CIA’s secret prison network.

The report’s findings, which committee president Dianne Feinstein called “shocking” and “in stark contrast to our values as a nation,” will probably not come as a surprise to most. It apparently contains evidence that the CIA not only tortured prisoners using methods that went above and beyond what the Department of Justice considers legal, but also that it deliberately misled Congress about the usefulness of the information the CIA obtained through those methods.

The complete 6,000-page report contains a copious amount of information that the public will likely never see. However, what we do know is that the current system does not work. “No, no my boy. Don’t tell me,” is a revealing quote. Human rights violations should not be hidden or concealed. Hidden acts of torture undermine the fundamentals of democracy and good governance.

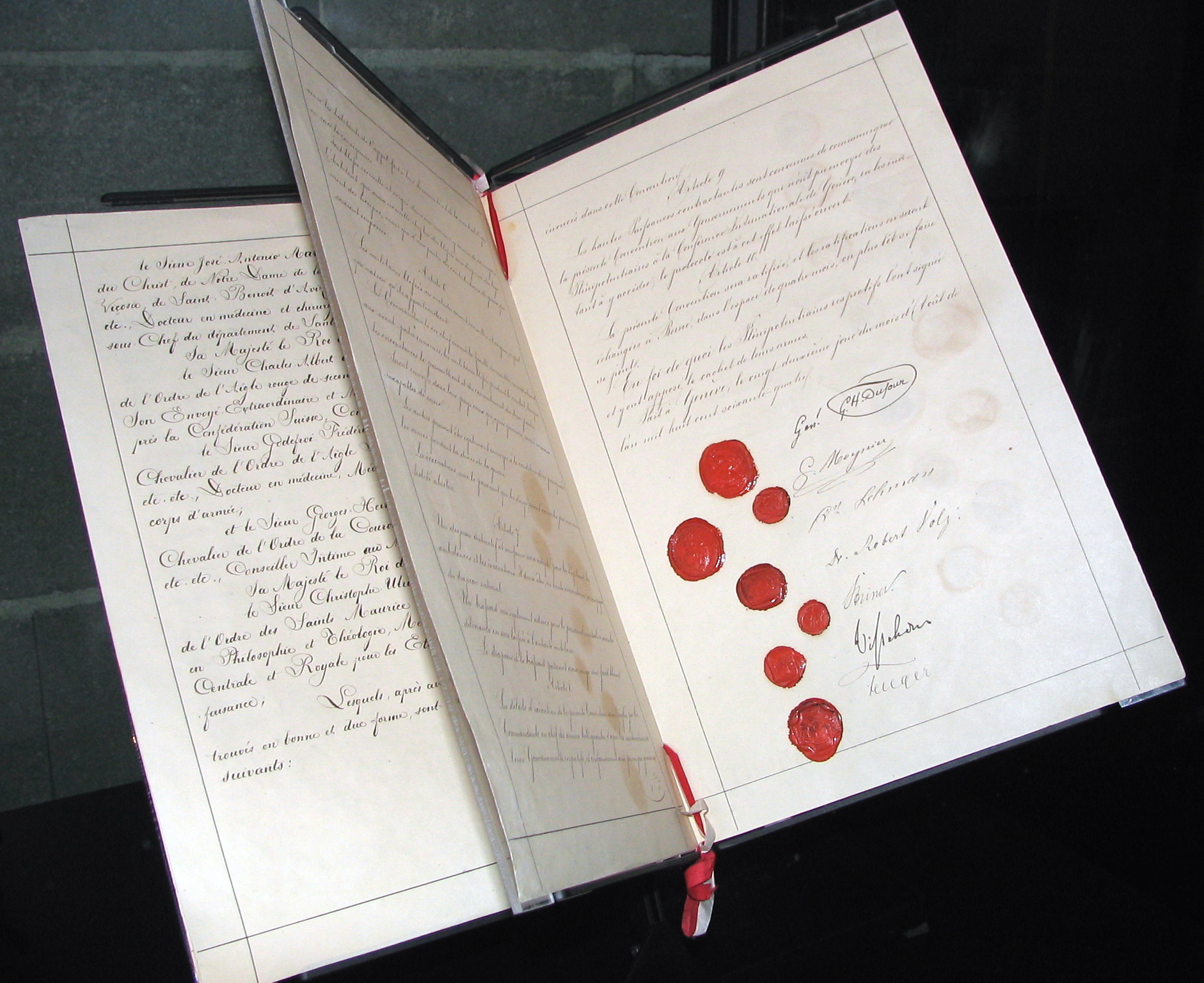

What to do? First of all, impunity for involved parties cannot be tolerated. When President Reagan ratified the United Nations Convention against Torture, he stated that it was an opportunity to “clearly express [the] United States opposition to torture.” One of the crucial elements of the Convention is the criminalization of torture and the obligation to prosecute those who practice it. If the information that we currently possess about the past decade’s occurrences does not lead to legal proceedings, then, nothing can stop these kinds of acts from happening again. Although President Obama said that “we need to look forward as opposed to looking backwards,” we must look to the past to continue building a world without torture.

Second, monitoring bodies must be strengthened. In addition to their independence from the executive branch and intelligence services, there are three requirements for their proper functioning: They must have access to relevant information, be able to question senior intelligence officials and finally, be allowed to freely publish their findings and recommendations. Without these three requirements, no one can be held responsible, and monitoring intelligence services is doomed to fail, and when monitoring fails, human rights are in grave danger.

Publishing the Senate committee’s report was an important step, but the unending struggles surrounding lengthy CIA documents and the persistent efforts by intelligence services to prevent people from accessing them shows that the criteria for effective monitoring are far from being respected.

In addition to Congressional monitoring, the supervision of prison conditions needs to be improved. Prisoners are not only mistreated in the CIA’s secret sites. These kinds of abuses can occur — and do occur — in federal prisons, police lock-ups, and immigrant detention centers. These abuses can happen in any place that lacks oversight.

There is an international mechanism in place to prevent torture under the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture — a mechanism that the United States is not yet a part of. The current Congress will probably not ratify the Protocol, but the experience of countries that did ratify it demonstrates that a national, independent system of detention site inspections stops torture before it begins.

The only way to learn from the past decade is to establish this kind of system, or else, those who look to the future will only see the past repeat itself.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.