This Tuesday, China took another step toward its Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the first multilateral financial institution not controlled by the United States or one of its allies. Today is China’s deadline and more than 45 other countries have petitioned to be one of the institutions’ founding members, despite the United States’ explicit rejection of the bank. Among the latest economies presenting their candidacy are Sweden, Spain, Taiwan — which does not have formal ties with continental China — and Norway, in spite of poor relations with Beijing after losing the Nobel Prize to Liu Xiaobo.

On April 15, the institution’s founding members will be announced, while China expects that it will begin operations by the end of the year. The headquarters will be housed in Beijing and will be led by Jin Liqun. Although it has been reported that its initial capital will be at least $50 billion signed — about 46 billion euros — and $100 billion more committed, there are numerous details about its inner workings that have yet to be finalized. It is not clear whether China will have veto power and the government seems reluctant to clarify this point. Its deputy finance minister, Shi Yaobin, assured last week that “It is an unfounded proposition that China seeks or forgoes veto power.”

The U.S. has had to turn to this lack of information to justify its concerns about the future organization and how it might weaken the World Bank or the Asian Development Bank. Washington has doubts about whether the AIIB will have strict enough governing or credit-extension standards. The countries that have applied for entry argue that once in, it will be easier to negotiate rules that guarantee internal transparency and strict standards. Yet, hiding in the background is a power struggle between the world’s two strongest economies. The refusal of the U.S. to participate in a development bank sponsored by China is met by China’s screaming absence in the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which the U.S. plans on signing with 11 more countries in Asia.

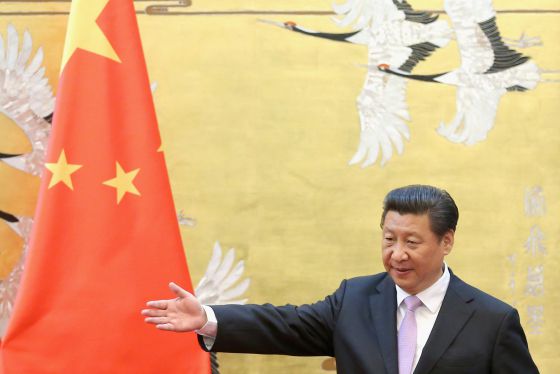

U.S. Secretary of Treasury Jack Lew was in Beijing this Tuesday where he met with Prime Minister Li Keqiang, among other officials. Lew expressed his country’s desire to “collaborate with China as that country furthers its financial reforms and becomes more integrated and assumes greater responsibility in the global financial system.”* China assures that it will use the organizations already in existence as a model and emulate their good traits while avoiding their weaknesses, such as excessive bureaucracy when it comes to granting credit. This weekend, Chinese President Xi Jinping highlighted the fact that the new bank would complement the World Bank and Asian Development Bank’s efforts. “Being a great country means taking on greater responsibility in the region and not seeking a greater monopoly in regional or global matters,” maintained the president.

Following in the steps of the U.S., countries like Australia and South Korea at first refused to participate, but, in the end, they applied for membership. Everything changed on March 12, when the U.K. announced its support, which surprised even Beijing, which was expecting an announcement some days later.

Britain’s minister of finance, George Osborne, made a simple calculation: As a founding member, his country would earn points to eventually become, as he desires, the great center of financial operations for renminbi (or Yuan) — the Chinese currency — in Europe. After the United Kingdom’s announcement, the rest of the European economies followed suit, eager to maintain harmony with the world’s second economy and to make way for the participation of their companies in projects financed by the bank. In the end, Asia’s needy sector in infrastructure has great potential.

Since Xi Jinping’s arrival to power, China has undertaken a much more energetic foreign policy and, with this bank, he has managed to increase China’s global influence. What’s more, China has earned credibility and experience in multilateral inversion. An area in which China is still a relatively new participant, despite having become one the world’s main credit providers: Its loans to Latin America and the Caribbean alone have increased 70 percent in 2014, now up to $22 billion according to the China-Latin America Finance Database. Its previous experiences, through the China Development Bank or Eximbank, have not always been pleasing. With the new bank, it will be able to make use of other countries’ knowledge, which has a longer tradition, while also holding onto the reins.

In the avalanche of applications to join, only one (that we know of) has been rejected: that of North Korea. Beijing blocked its petition when it refused to provide financial data.

*Editor’s note: The original quotation, accurately translated, could not be verified.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.