One day, the future first lady of the United States discovered that her husband, the future president, was cheating on her. In that instant, her life changed forever. Although she thought about divorcing him, she finally reconsidered and in a cold and pragmatic manner decided to remain at his side, but with one condition: She would abandon the role of the selfless wife and develop an intense public role with her own political agenda. We are not talking about Hillary Clinton but Eleanor Roosevelt.

This past Nov. 7, on the eve of the U.S. presidential election, was the 54th anniversary of the death of one of the most interesting women in the history of American politics. The daughter of a well-off New York family, Eleanor did not need to change her surname when she married: Her father was the younger brother of former president Theodore Roosevelt. She was married at 21 years of age to her distant cousin, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the president who would eventually lift the United States out of the Great Depression with the “New Deal.”

Life forced her to be strong: Her mother and younger brother both died of diphtheria when she was just 8 years old, and her father, an alcoholic, would die two years later after leaping from a window at a sanitarium during a spell of delirium tremens. She was intelligent and prepared, and right after becoming first lady in 1933 she showed her dissatisfaction with the role that until then had been reserved for the spouses of presidents, and she continued her intense work. Her husband’s illness, which confined him to a wheelchair by 1921, helped ignite her presence in political life; in fact, she wound up holding more meetings and press conferences than the president did.

She quickly became one of the main defenders and promoters of the New Deal, even to the point of participating in the inspections of its programs. It was in this way she noticed that in the southern states, the black population was benefiting proportionately less from public aid, which led to her role as an activist in the African American civil rights movement. Nor did she forget the rights of homosexuals, which would undoubtedly influence the romantic relationship she had with a female reporter for the Associated Press.

Also under the New Deal, she fought for wage equality for women. She worked behind the scenes to make lynching a federal crime. She also tried to fight the wave of hatred toward Japanese residents in the United States after the attack on Pearl Harbor, believing that it was generating “great hysteria against minorities,” and she even actively opposed Order 9066 that her husband approved. which resulted in numerous Japanese-Americans being sent to internment camps. She also defended asylum for the Jews being persecuted by the Nazi regime, but the fear that there could be terrorists among the political refugees weighed heavily on the president, who went as far as to restrict their immigration.

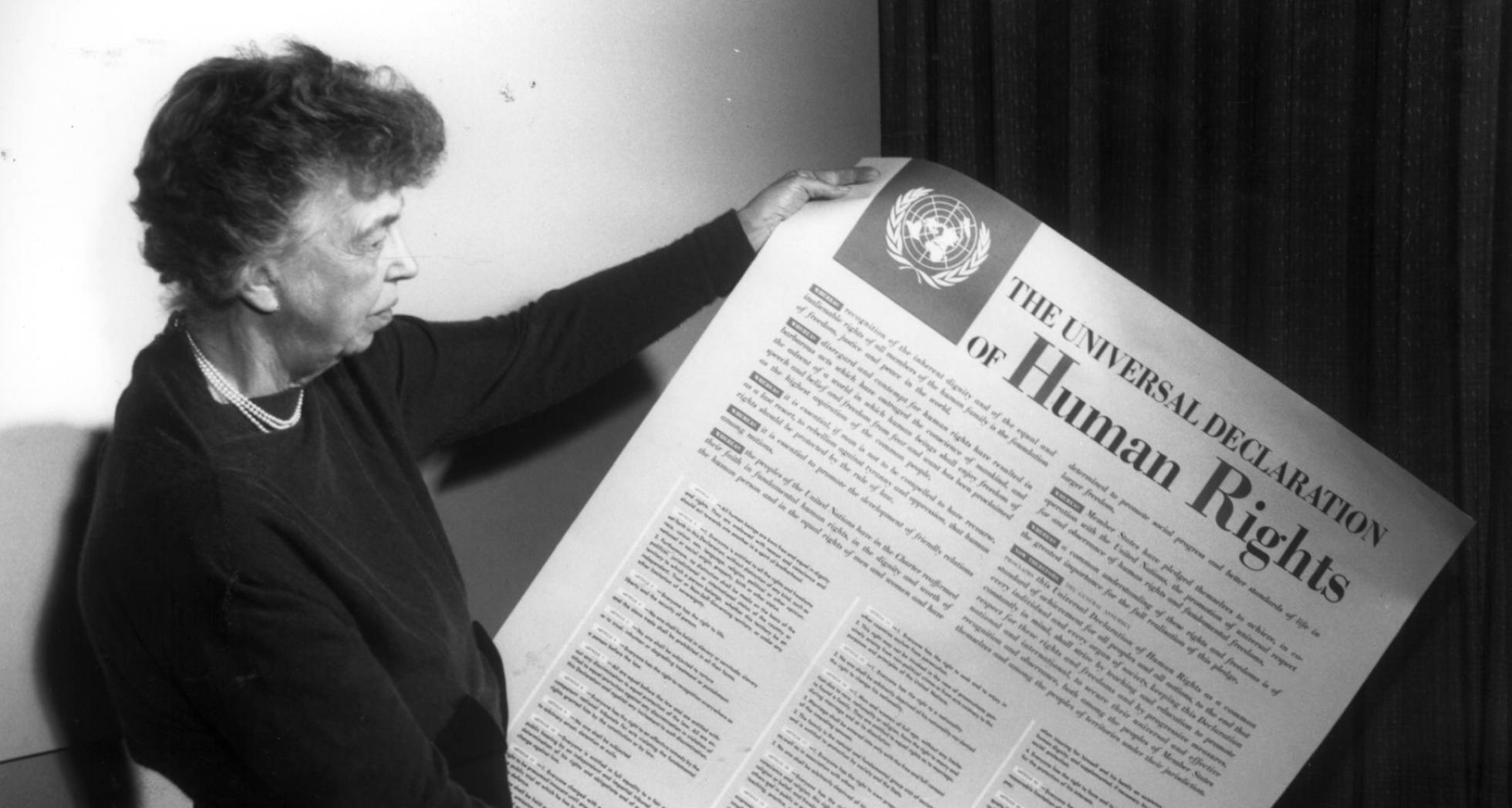

Following the death of President Roosevelt in April of 1945, Eleanor had to face the embarrassment of discovering that her husband’s former lover had accompanied him to his deathbed. But still, she rebounded again. President Roosevelt’s successor, Harry S. Truman, would name her as a delegate to the United Nations, where she would become the first female chair of the U.N. Human Rights Commission and a key player in the drafting and subsequent adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

For a time she flirted with the possibility of running for president of the United States. She harbored that hope until Truman decided to support the governor of New York as the democratic candidate. She never brought it up again and instead, for many years, opted to support the presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson, another fascinating character of many stories, such as when an admirer told him that all the intelligent people in the United States were going to vote for him, to which he replied: “I’m afraid that won’t do—I need a majority.”

Although Eleanor had enormous popularity, her activism and her assertiveness earned her much antipathy. She was accused of being anti-American for defending the Japanese immigrants; of being a fantasist and idealist for promoting a city-cooperative in Arthurdale where homeless miners were resettled; of being a hypocrite for including a segregationist city within the pilot cities of the New Deal and allowing it to carry her name (Eleanor, West Virginia); of being sectarian for favoring affirmative action for women and for some time only allowing female reporters access to press conferences; of showboating for visiting the troops in the South Pacific to offer them encouragement; of being foolhardy for trying to take in Jewish refugees persecuted by the Nazis; and even of being adulterous, immoral and a liar.

If on Nov. 8 the ghost of Eleanor Roosevelt would have come out from her grave to bear witness to the American elections, she would have been disappointed.* It is likely that, once the vote count was over, she would have slipped stealthily into the Democratic Party headquarters, approached a heart-broken Hillary Clinton and placed a hand on her shoulder while whispering some words of comfort in her ear. She also knew what it’s like to be judged for the infidelities of her husband, for daring to have her own political career while being the First Lady, and for coming from a family that was well-off and linked to the establishment; for evolving and changing her opinion on important topics like gay rights; for being tough, cold and pragmatic, which were values not seen as negative in male politicians; and even, of course, for committing errors and falling into contradictions, as all human beings do, especially politicians.

Later, slowly, she would have returned to her grave thinking about the values for which she had always fought: rights for racial minorities, immigrants, homosexuals, women, disadvantaged people and those evicted after a great economic crisis. Upon closing her headstone again she would have sighed as she wondered when would be the next time that she could go out again to try to see a women reach the presidency of the United States.

*Editor’s note: “Nov. 8” is a correction to the original article, which referred to Nov. 7 as election day.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.