A meeting between Trump and Kim provides North Korea with sought-after legitimacy as a state, writes Remco Breuker.*

Kim Jong Un made a dramatic turnaround last week: He wants to talk about nuclear disarmament and is willing to meet Donald Trump in person. I did not see that coming. North Korea’s conduct on the international stage reads like a cheap thriller that is hedged with unlikely developments. A spectacular attempted murder at a Malaysian airport, a missile test, and all that followed up by an unexpected offer of total peace, which makes everything right again.

But in that vortex of unexpected things, some things threaten to disappear. The role of South Korea, for example. President Moon Jae In has made something from nothing in the past few months. Like a Baron Munchausen, he has managed to pull himself up by his own hair from the swamp called North Korea. It seems now that he has brought North Korea and the U.S. to the table without any actual promises from anybody. That is international statesmanship of the highest order – and at the same time morally irresponsible and unwise.

Moon has been able to repackage two propositions from North Korea, which have been lying on the table for 20 years, and offer them to the White House. North Korea has always said it’s willing to disarm if the “hostile policy” toward North Korea is stopped. In the North Korean interpretation, this means that the U.S. Army must withdraw from South Korea. But the question is whether the White House has “understood” this as such.

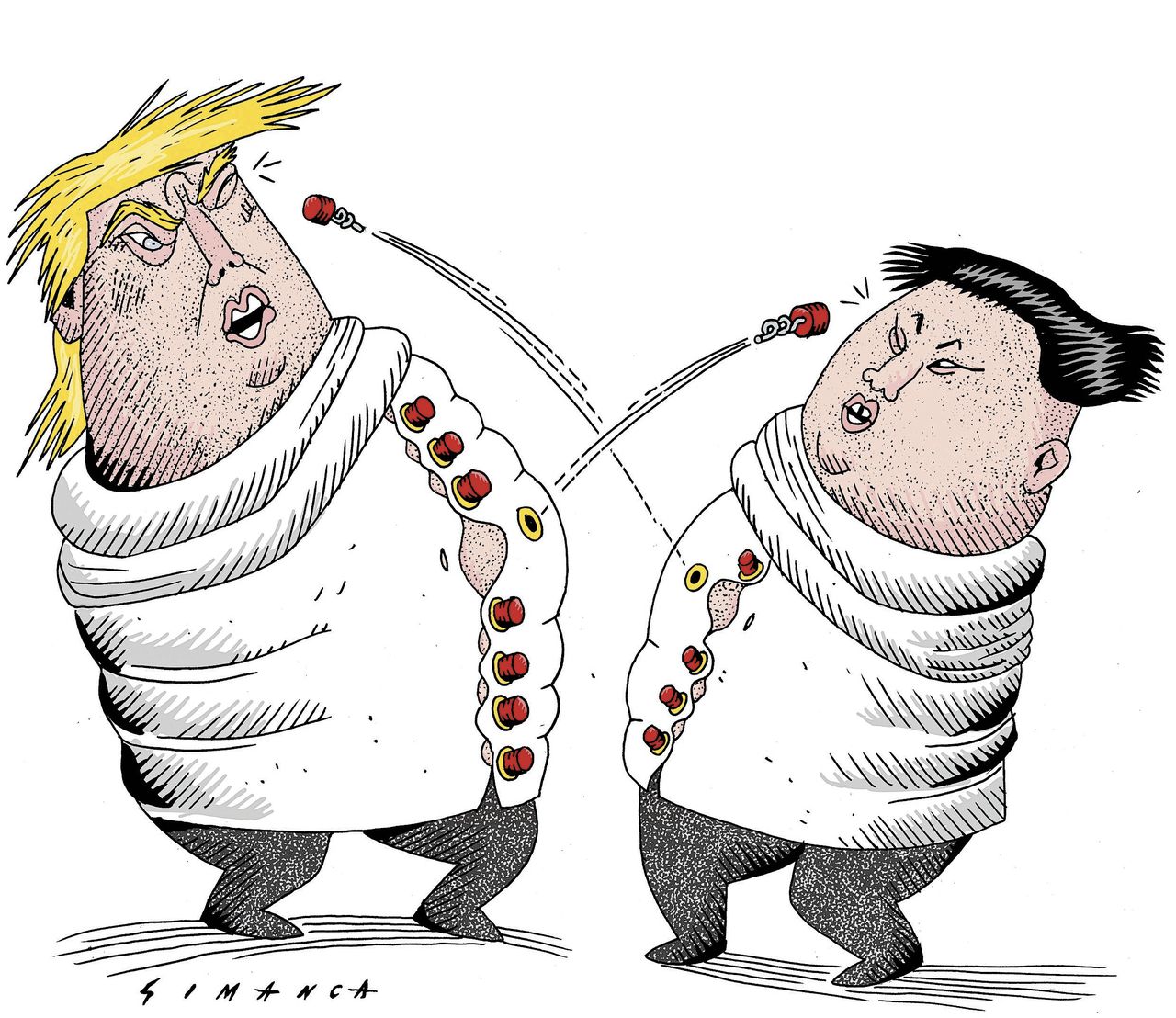

By having Moon’s envoys hand-deliver Kim’s letter, Moon has apparently successfully appealed to Trump’s ego. Earlier American presidents have always steered away from a meeting, as it would lend North Korea the much sought-after legitimacy as a regular state; surely the human rights situation there would not allow it. But Trump does not have any North Korea experts around him who can interpret such overtures.

It is only fair to say that Trump has not merely walked into a carefully prepared, united Korean trap. The sanctions accompanying his inconsistent verbal statements were consistent and had effect. So much so, that North Korea feels obliged to do something about it as quickly as possible. In April, the top meeting with Moon is scheduled; in May the meeting with Trump. This is bizarrely fast. The bottom of the treasure chest is in sight, so speed is of the essence for Pyongyang. The proposal for nuclear disarmament is what seems to have brought Trump to the table. But this is already two decades old, and has always been a paper proposal. Is it different this time around?

Analysts seem to agree: North Korea will never voluntarily disarm under this regime. Thus, it is very likely that during the negotiations, the very well prepared North Koreans will negotiate the Americans off the table and leave with an implicit recognition of their status as a nuclear power. I do not rule out a surprise finale, but common sense and recent history call for caution in one’s expectations.

The most important thing that this spectacular and mediagenic whirlwind of development threatens to make disappear is this: It is not so much the North Korean missiles that form a threat. North Korea itself is a much more direct threat. North Korea is the institutionalized denial of human and individual freedom.

In North Korea, do you think differently, act differently, believe differently, love differently? Then a concentration camp is nearby. These camps serve a dual purpose: Political and other dissidents are eliminated, and profit is generated by making prisoners perform forced labor until they die.

North Korea shows, just like Bashar Assad’s Syria (where North Korean poison gas was used yesterday in Ghouta) and Xi Jinping’s China, that dictatorships that do not respect fundamental human rights can be successful states, and that economic prosperity does not have to lead to political freedom. That total surveillance society is present in North Korea. It is very undesirable to combine this with access to international markets, South Korean know-how and technology, and overall social acceptability.

Human rights are crucial in this respect, not out of an idea prompted by a Western feeling of superiority that human rights are universal, but because the North Korean system as it is, simply is incapable of honoring fundamental human rights. Everything would fall apart. Hence, the frenetic effort by South Korea to avoid talking about human rights.

The proposed summit between Trump and Kim – should it happen, of course – can yield a lot. This is especially so for North Korea, but who knows what will happen. The main point, however, is that the summit will not broach the real problems. Moon, Kim and, to a lesser extent, Trump, have conjured a North Korea where the biggest problem is nuclear missiles.

If only that were true.

*Remco Breuker is a professor of Korean studies at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.