The 'Disunited States of America'

When Americans celebrated Thanksgiving, 'they might well have given thanks that they continue to be one nation under one flag.' Given the fissures in American society and the pressure exerted by immigrants, according to this op-ed article from Peru's El Comercio, it would be a mistake to assume that the U.S., or other nations in the Americas, will remain intact.

By Andrés Oppenheimer

Translated by Richard Hauenstein

November 4, 2005

El Comercio - Original Article (Spanish)

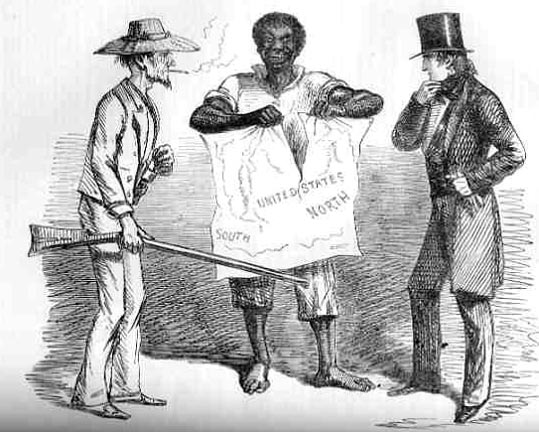

Civil-War Era Cartoon Illustrating the Fissures Between the American North and South.

When North Americans celebrated Thanksgiving Day, they might well have given thanks that they continue to be one nation under one flag; judging from some books I have read, it's not necessarily a certainty that this state of affairs will continue for much longer.

More and more futurologists are predicting that not only the United States, but Mexico and other countries in Latin America might become divided into smaller states in the decades to come. The flag to which many of these countries swear allegiance today may well not be the same flag to which their children or grandchildren swear loyalty.

Last year, Samuel Huntington, the well-known political historian from Harvard University, made major headlines with a book titled, "Who We Are," in which he warned with alarm that the territorial integrity of the United States is being threatened by the growing Hispanic population in the country.

Huntington's book argues that, unlike other immigrants in the past, Hispanics come from a neighboring country oppressed by poverty, come to the United States in massive numbers, are concentrated in but a few states, and continue to speak their native language once there.

Even more serious, says Huntington, is that they come from a neighboring country [Mexico] still wounded from having lost half its territory [over a million square miles], and that they "can achieve a historic reclamation from the United States." If you want to know why I think Huntington's arguments are nothing but a string of Hispanophobic foolishness, I invite you to read my column of February 26, 2004.

Today, a new book is about to go on sale, written by Juan Enríquez, a former Harvard professor who is now the founder of a company dealing with human gene mapping. In it, he makes a much more intelligent analysis of the possibilities for the creation of new states – or countries – in the Americas.

His new book, "The Disunited States of America," published in English by Crown Business, reminds us that, in 1950, the United Nations had 50 member states. Today, that number has grown to 191.

While between 1900 and 1950, an average of 1.2 new countries were formed per year, between 1950 and 1990 that number grew to 2.2 new countries a year; and from 1990 to the present, the average has risen to 3.1 per year.

"We have paid little attention to the fact that many countries have been divided or have disappeared, because our hemisphere has enjoyed a surprising stability," says Enríquez. "We haven't had new frontiers on the American continent since 1910. But this stability may well be coming to an end."

Countries, like marriages or corporations, frequently come to a breaking point, at which they either split up, or they die.

Generally, it is the richest regions – not the most neglected – that we find to be "dis-unified." Such regions feel that they are giving more than they are getting in return to the societies to which they belong, and they assert that they want to leave.

Enríquez argues that in the United States, the richer states like New York, New Hampshire, Massachusetts and Minnesota are constantly compelled to pay more in taxes than they receive in return. Noting that the majority of these states vote Democratic, and are not part of the Southern "Bible Belt" which votes for President Bush's party, shows clearly that the people of these states "have much more in common with Canadians than they do with those who live in States that are pro-Bush."

Enríquez doesn't anticipate a Mexican reconquest of the Southern U.S. states. On the other hand, he says that perhaps the Hispanics of northern Mexico and the southern United States will seek to create autonomous states, if they feel that they have less and less in common with their central governments. Look at what is happening in England and Spain, he says.

The Approximate Extent of the U.S. Bible Belt

The Approximate Extent of the U.S. Bible Belt

In Mexico, Enríquez sees possible breakaways in four regions or countries: the North (the free trade region), central Mexico (Mexico City and its surrounding area), indigenous Mexico (Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca), and New Maya (Yucatán, Campeche and Quintana Roo).

My opinion? I doubt we will see a long line of new countries in the Americas, though it would not surprise me if the prosperous region of Santa Cruz in Bolivia might consider that road, if radical Indian candidate Evo Morales tries to seize power by means of a "people's revolt" if he is defeated in next month's presidential election.

But no matter which ancient world map we might remember, it is clear that things change. The most likely outcome, as described by Enríquez himself, is that the less governments show positive results to all their citizens, the more we will see a growing tendency in these discontented regions to seek greater autonomy within the context of free associations or regional common markets.

The elements for separation are already there: regional discontent, transnational projects and governments increasingly incapable of meeting the expectations of their people and.

Perhaps what's going on in Europe will not be long in coming to our continent.