Time for a Holiday for ALL Americans

Have the people of the United States hijacked the term 'American' and the celebration of 'American' independence? According to this article from Canada's Le Devoir, the expression 'America for the Americans' was first uttered by U.S. President James Monroe in 1823, and referred to all of the inhabitants of the Americas that had thrown off their colonial rulers. Shouldn't we, therefore, share an Independence Day?

By Alain Lavallée, professor of management and the social sciences

Translated By Kate Brumback

July 5, 2006

Canada - Le Devoir - Original Article (French)

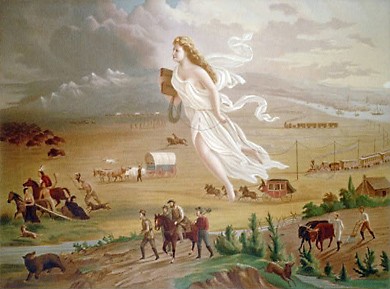

This 1872 painting called 'American Progress' is an allegorical

This 1872 painting called 'American Progress' is an allegorical

representation of Manifest Destiny. In the scene, Columbia, a 19th

century personification of the United States, carries the light of

'civilization' westward, with American settlers, stringing telegraph

wire as she travels. American Indians and wild animals flee - or

lead the way - into the darkness of the 'uncivilized" West.'

[ Manifest Destiny ]

Manifest Destiny ]

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It is

clear that the 4th of July is an important holiday for the United

States, but is it really an "American" holiday? Wouldn't it be more

appropriate to celebrate "Americans" on October 12 or even June 21?

Just like

the term "European" can refer to a Frenchman, a German, an Italian or

a Dane, the term "American" should just as readily be used to refer

to a Mexican, a Canadian, and a Brazilian, an Argentine or a citizen of the

United States. Since we live on and share this continent of the Americas,

Canadians are Americans, like Italians are Europeans.

The "European

Parliament" or the "European government" designates institutions

that include a large number of countries on the European continent. This is not

the case with the current usage of the expressions "American government"

or "American dollar," because they only refer to the government of

the United States or the money of the United States and not those of Canada or

Mexico. At a time when different types of associations exist and evolve (NAFTA,

Mercosur, etc.), it is becoming more and more appropriate to reserve the title "American"

for every inhabitant (or institution) of the Americas and not only those from

the United States. But where does this practice come from, of labeling "American"

the citizens and institutions of the United States alone, and not those of

Costa Rica or Canada?

James Monroe, fifth President

James Monroe, fifth President

of the United States,

coined the

phrase, 'America for the Americans.'

[ James Monroe ]

James Monroe ]

---------------------------------------------

'AMERICA FOR THE AMERICANS'

It was in

a speech to the United States Congress on December 2, 1823, that President

James Monroe  claimed "America for the Americans." This short phrase, which later

became a doctrine, was actually a brusque warning to European countries, warning

them to stop meddling in the political affairs of the Americas.

claimed "America for the Americans." This short phrase, which later

became a doctrine, was actually a brusque warning to European countries, warning

them to stop meddling in the political affairs of the Americas.

This 1823

warning was passed down through history as the Monroe Doctrine.

On the one

hand, it was recognition of the newly-won independence of parts of the Spanish

empire: Venezuela in 1811, Grande Colombia in 1819, Mexico in 1821, Peru in

1821, the recognition of Argentina and Chile in 1823, etc. In this cry of "America

for the Americans," made in 1823, 'Americans' included Mexicans and

members of other nascent Latin American countries.

On the

other hand, this message in part revealed the expansionist ambitions of the

former British colonies that in 1776 became the United States. In 1803, they purchased

the Louisiana Territory from France  , which covered a twentieth of the current United States. In addition, in

order to gain access to the Gulf of Mexico, the United States had just gone to

war with Spain. This resulted in a treaty giving it Florida (1819).

, which covered a twentieth of the current United States. In addition, in

order to gain access to the Gulf of Mexico, the United States had just gone to

war with Spain. This resulted in a treaty giving it Florida (1819).

James K. Polk, eleventh President

James K. Polk, eleventh President

of the United States,

a vigorous

backer of Manifest Destiny.

[ James K. Polk ]

James K. Polk ]

--------------------------------------------

Then, in

the 1840s, this warning became "Manifest Destiny  " The politicians in the United States amazingly came to believe that the

destiny of their country was to occupy the entire continent, all of America.

President Polk

" The politicians in the United States amazingly came to believe that the

destiny of their country was to occupy the entire continent, all of America.

President Polk  claimed that, "not only must the United States preclude European

intervention on this continent … but nothing precludes any portion of the

territory of this continent from becoming part of the United States."

claimed that, "not only must the United States preclude European

intervention on this continent … but nothing precludes any portion of the

territory of this continent from becoming part of the United States."

The

United States then declared war on Mexico. It annexed Texas in 1845. It

obtained the California territories in 1848 (California, Arizona, Nevada, Utah,

New Mexico). It threatened Great Britain and reclaimed the British territories

in the northwest. In 1846, Great Britain ceded the territories south of the 49th parallel (Oregon, Washington, etc.).

When the

Russian Cossacks were implanted in Alaska, the politicians in the United States

feared that their further advance into American territory. On March 30, 1867,

the United States purchased the territory of Alaska from the Russians, and then

invited the territories between Alaska and the United States, and to the west

of the Rockies, to be annexed by the United States.

To combat

this expansionist threat, this "Manifest Destiny" of the United

States, Great Britain prepared the British-North America Act  , leading to the creation of Canada three months later. Starting on July 1,

1867, Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia constituted an "American"

country. The United States gave up annexing these English colonies because they

were now part of an "American" country. Their inhabitants were "Americans."

But British Columbia hesitated. It wasn't until three years later, in 1870,

that it joined Canada rather than the United States.

, leading to the creation of Canada three months later. Starting on July 1,

1867, Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia constituted an "American"

country. The United States gave up annexing these English colonies because they

were now part of an "American" country. Their inhabitants were "Americans."

But British Columbia hesitated. It wasn't until three years later, in 1870,

that it joined Canada rather than the United States.

Pre-World War I Cartoon Dipicting the Monroe Doctrine, with Uncle Sam

Pre-World War I Cartoon Dipicting the Monroe Doctrine, with Uncle Sam

drawing the line for European countries considering meddling in Latin

America. [New York Herald]

[ The Monroe Doctrine]

The Monroe Doctrine]

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Americans"

are celebrated on June 24, July 1 and July 4. But on June 24, they are

Quebecois; on July 1, they are Canadian; and on July 4, they are from the

United States.

When might

we schedule a holiday celebrating all Americans? The two most pertinent dates

would be October 12 or June 21. On October 12, 1492, Columbus landed on the

American continent, and we all followed. Or perhaps we should choose June 21,

the summer solstice. This is the holiday of the indigenous people, the

Americans who have lived on this continent for over 10,000 years.

French Version Below

Le 4 juillet, fête des «Américains»?

Alain

Lavallée

Professeur

au collégial en sciences humaines et en gestion

Édition du mercredi 5 juillet 2006

On ne

peut douter que le 4 juillet soit une fête importante pour les États-Unis, mais

est-ce bien la fête des «Américains»? Le 12 octobre ou même le 21 juin ne

seraient-ils pas plus appropriés pour célébrer les «Américains»?

De la

même façon que le terme «Européen» peut référer à un Français, à un Allemand, à un Italien ou à un Danois, le terme «Américain»

devrait servir à désigner aussi bien un Mexicain, un Canadien, un Brésilien, un

Argentin ou un citoyen des États-Unis. Ne serait-ce que parce que nous habitons et partageons ce continent des Amériques, les

Canadiens sont des Américains, tout comme les Italiens sont des Européens.

Le

«Parlement européen» ou le «gouvernement européen» désignent des institutions

qui concernent un grand nombre de pays du continent

européen. Ce n'est pas le cas de l'usage actuel des expressions «gouvernement

américain» ou «dollar américain» puisqu'elles ne désignent que le gouvernement

des États-Unis ou la monnaie des États-Unis et non celle du Canada ou du

Mexique. À l'heure où différentes formes d'associations des pays d'Amérique

existent et évoluent (ALENA, Mercosur, etc.), il

devient de plus en plus approprié de réserver l'appellation «Américain» à tout

habitant (ou institution) des Amériques et non plus aux seuls États-Uniens.

Mais d'où vient cette pratique de qualifier d'Américains les citoyens et les

institutions des États-Unis et non ceux du Costa Rica ou du Canada ?

«L'Amérique

aux Américains»

C'est

dans son discours au Congrès des États-Unis du 2 décembre 1823 que le président

James Monroe a clamé «l'Amérique aux Américains». Cette courte phrase, qui

devint doctrine par la suite, était de fait un sévère

avertissement lancé aux pays européens afin de les avertir de ne plus

s'immiscer dans les affaires politiques des Amériques.

Cet avertissement lancé en 1823 est passé dans l'histoire sous le nom de doctrine

Monroe. D'une part, il constituait une reconnaissance des indépendances

nouvellement arrachées des rets de l'empire espagnol : le Venezuela en

1811, la Grande Colombie en 1819, le Mexique en 1821, le Pérou en 1821, la

reconnaissance de l'Argentine et du Chili en 1823, etc. Dans ce cri «l'Amérique aux Américains» lancé en 1823, ces Américains étaient aussi des

Mexicains et les membres des autres nations latino-américaines naissantes.

D'autre

part, ce message révélait en partie les ambitions

expansionnistes des anciennes colonies britanniques devenues les États-Unis en

1776. En 1803, ils avaient racheté de la France la

Grande Louisiane, qui couvrait une vingtaine d'États actuels des États-Unis. De

plus, afin d'avoir accès au golfe du Mexique, les États-Unis venaient de faire

la guerre à l'Espagne,. Il en

avait résulté un traité leur cédant les terres de la Floride (1819).

Puis,

dans les années 1840, cet avertissement devint

«destinée manifeste». Les politiciens des États-Unis se surprirent à croire que

le destin de leur pays était d'occuper tout le continent, toute l'Amérique. Le

président Polk clama que non seulement «les États-Unis ne peuvent laisser faire

une intervention européenne sur ce continent [...]

mais [que] rien ne s'oppose à ce qu'une portion du territoire de ce continent

s'unisse aux États-Unis».

Les

États-Unis font alors la guerre au Mexique. Ils annexent le Texas en 1845. Ils s'emparent de la Grande

Californie en 1848 (Californie, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Nouveau-Mexique). Ils menacent la Grande-Bretagne et réclament les territoires

britanniques situés au nord-ouest. En 1846, la

Grande-Bretagne cède les territoires au sud du 49e parallèle (Oregon, État de

Washington, etc.).

Alors que

les cosaques russes s'étaient implantés en Alaska, les politiciens des

États-Unis craignaient qu'ils n'avancent plus loin dans les terres d'Amérique.

Le 30 mars 1867, les États-Unis achètent des Russes le territoire de l'Alaska,

puis invitent les territoires situés entre l'Alaska et les États-Unis, à l'ouest des Rocheuses, à s'annexer aux États-Unis.

Pour

faire face à cette menace expansionniste, à cette «destinée manifeste» des

États-Unis, la Grande-Bretagne a préparé l'Acte de l'Amérique du Nord

britannique, créant trois mois plus tard le Canada. À partir du 1er juillet

1867, le Québec, l'Ontario, le Nouveau-Brunswick et la

Nouvelle-Écosse ont constitué un pays «américain». Les États-Unis ont renoncé à

annexer ces colonies anglaises puisqu'elles formaient dorénavant un pays «américain». Ses habitants

étaient des «Américains». Mais la Colombie-Britannique se fera tirer l'oreille. Ce n'est que trois ans plus tard, en 1870, qu'elle se joindra

au Canada plutôt qu'aux États-Unis.

Le 24

juin, le 1er juillet et le 4 juillet des Américains

sont fêtés. Cependant, le 24 juin, ils sont Québécois;

le 1er juillet, ils sont Canadiens; et le 4 juillet, ils sont États-Uniens.

Quand pourrait avoir lieu une fête célébrant tous les Américains? Les deux dates les plus

pertinentes seraient le 12 octobre ou le 21 juin. Le 12 octobre 1492, Colomb

touchait le continent américain, et nous l'avons tous

suivi. Le 21 juin, jour du solstice d'été, est la fête

des peuples autochtones, c'est-à-dire des Américains qui habitaient ce

continent depuis plus de 10 000 ans