In the afterglow of the Obama-mania that swept over Berlin and the rest of Europe there is a lot for us to think about. The U.S. presidential elections are important, but are Europeans already a bit too interested in them?

At first glance the presidential elections in the U.S. are entertainment on a grand scale, with candidates to match. Both the Republican John McCain, and the Democrat Barack Obama have spent their respective lives of differing length constructing an appearance and charisma worthy of a presidency.

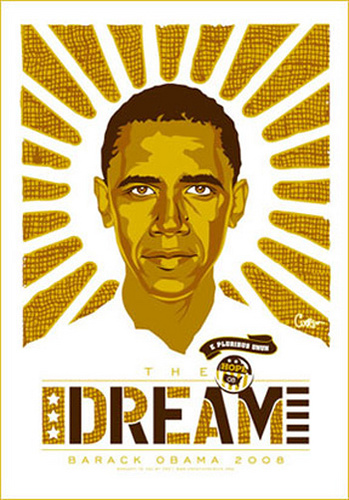

The Europeans interest in the elections stems from the great power wielded by the U.S. president, and its global impact. The presidents power, however, primarily serves the voters–that is the U.S population–not the rest of the world, in a democracy it could not be any other way. One reason for the Europeans interest is an apparent desire for a change, in trans-Atlantic relations as well as global politics in general. Hopes placed into a single leader are, however, easily unreasonable in both nature and scale. If the shine of the heros cape placed on Obamas shoulders is dazzling, then George W. Bush is in European minds robed in dark. The black-and-white world view of Bush has apparently impressed itself on European minds well.

In addition to the aforementioned reasons originating from America, the interest in these elections is fueled by a haunting specter of the state of democracy in Europe, currently in dispute over the Lisbon treaty. Charismatic leaders are no longer a part of the European landscape. When was the last time that a European politician has had over 200,000 listeners, as Obama did in Berlin?

The previous century taught Europeans to fear overly charismatic or inspiring politicians. What has especially made Europeans cringe has been the politicians habit of pandering to nationalist passions, which were, and still are, strongly linked to ethnic backgrounds in Europe. From a people led democratically by a charismatic leader there was only a small step into the genocide of another people. That is why perhaps Europeans find it safer to feel politically passionate towards leaders with whom no morally or politically binding tie can possibly emerge.

The European project for peace–the E.U. as its central manifestation–has focused on channeling political power away from charisma and nationalist passions. Legislation has become bureaucratized and most of the decisions are made in Brussels, the capital of a nation divided, or on the brink of even splitting apart. Belgiums problems show that the E.U. has not dispelled ethnic and linguistic fault-lines; rather it has provided them a safe environment to become highlighted in.

History has left Europe in a topsy-turvy state. The E.U. has spread the message of democracy to its surroundings, all-the-while making the people of its member states vote and vote again until they understand to vote the right way. Ireland might have to arrange new votes on the Lisbon treaty for as many times as it takes for the treaty to be accepted. When the Irish in their first vote rejected the treaty, one could pick up some concern in the tone of voice of European leaders- and even contempt for democracy. A people expressing their will ought not constitute a crisis in the minds of European leaders.

In the U.S. the people are being listened to now. The upcoming presidential elections are largely focused on criticism of the current government under Bush. In the election process this governments actions-from torture to financial policies–will be criticized without mercy.

The American idea has great importance when a corrective move is made to get back on the right course. If Americans feel they have veered off course they can seek protection in, and refer to, the declaration of independence as well as the constitution. The American idea is not abstract, but verifiable by anyone from the relevant documents. In the end, peoples worship is not directed towards the political leaders–no matter how charismatic they may be –but rather towards the constitution and the values and ideas held within it.

Democracy, or rather democracies, in Europe do not have the benefit of a national creed or idea. The E.U. has an idea of peace and co-operation but not a people of its own while the member states have the people but not a creed. In Europe the message of ascending charismatic leaders is divisive rather than unifying. They appeal to a creedless form of nationalism that causes a separation of immigrants from the general population. Thus charismatic leadership is not associated with noble ideals, but rather with primitive and tribal thinking.

The greatest gift of Obama-mania and the presidential election to Europe could be a resurgence of concern for the state that European democracy is in. The popularity of especially the leaders of large countries in Europe is waning- from Gordon Brown to Silvio Berlusconi and Nicolas Sarkozy. In the light of history one does not even dare to wish for a widespread political ecstasy on our continent. Yet the well-being of democracy depends on at least some level of trust in the system of democracy and in those who wield the power in it. A democratic representative shunning his or her voters is not worth tuppence.

For Europeans to become as interested in their own future as the presidential elections of the United States, it is necessary to let the people of European nations to decide upon the political shape of their continent.

The War against Terrorism has caused the U.S. government to deviate from American core-values. In contrast to the Americans, there is no happy ending in sight for Europeans in their problematic relationship with democracy.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.