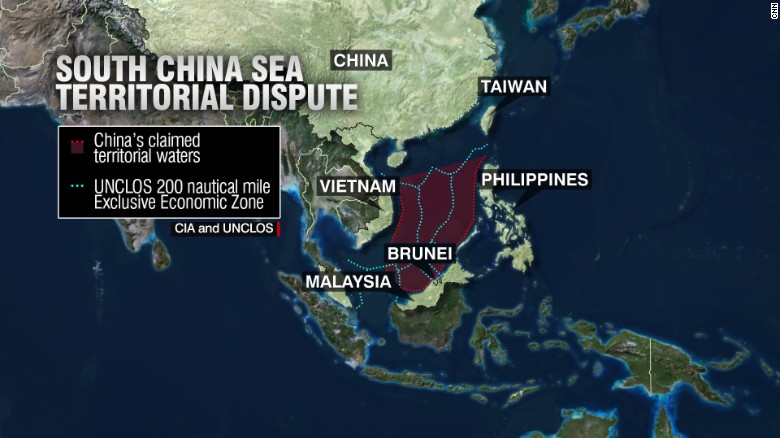

Lately, due to suspicions that China has deployed anti-aircraft missiles on Woody Island, dispatched Shenyang J-11 fighters and Xian JH-7 fighter-bombers into Paracel Islands airspace and deployed a radar system in the Spratly Islands, tensions in the South China Sea have flared sharply. The U.S. has accused China of militarizing the South China Sea in a high-profile manner. However, with the beginning of operations of the Chinese-built lighthouses in Cuarteron Reef, Johnson South Reef and Subi Reef, the capability of ships sailing in the South China Sea to safely navigate and aid in navigation will greatly increase, clearly showing who exactly is providing public international products for the freedom and safety of sailing in the South China Sea. In fact, it is no exaggeration to say that almost everyone on earth knows that the real force behind the unstable situation in the South China Sea is the U.S.

In recent months, U.S. warships have frequently entered the South China Sea to show off U.S. military presence, even challenging China’s territorial sovereignty. On March 1, ships of the U.S. 7th Fleet, the aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis, accompanied by the cruisers USS Mobile Bay and USS Antietam, destroyers USS Stockdale and USS Chung-Hoon and other vessels entered the South China Sea. The fleet’s flagship, the USS Blue Ridge, also entered the South China Sea at the same time. On Jan. 30, the US destroyer USS Curtis Wilbur came within 12 nautical miles of Triton Island, which is not disputed territory. Cui Tiankai, Chinese ambassador to the U.S., pointed out in an interview with CNN that this is “a very serious provocation, politically and militarily.” On Oct. 27 last year, the U.S. Navy’s guided missile destroyer, the USS Larsen, sailed within 12 nautical miles of the Spratly Islands’ Subi Reef and Mischief Reef for several hours. On Nov. 5, U.S. Secretary of Defense Ash Carter boarded the aircraft carrier USS Theodore Roosevelt and sailed at about 150-200 nautical miles south of the Spratly Islands for more than three hours. On Dec. 10, two U.S. B-52 bombers flew within two nautical miles of the Spratly’s Cuarteron Reef at low altitude. Is it possible to claim that this series of actions by the U.S. military is not against China or has nothing to do with China?

On April 4, the United States and the Philippines kicked off their annual joint military exercises, called Balikatan 2016 (Balikatan is the Tagalog word for “shoulder-to-shoulder”), and are expected to continue until April 15. According to reports, some 10,000 U.S. and Philippine officers and soldiers are participating, and the contents of the exercises include “island seizing exercises” and special operations. In recent years, the annual U.S.-Philippines military exercises have been expanding in size; drill sites are getting increasingly close to sensitive areas and are full of provocation. Eighty Australian officers and soldiers were also invited to participate in the exercise this year, and Japan was invited to participate as an observer. Clearly, increasing the Balikatan annual military exercise’s size and military intensity is an important action of the Asia-Pacific strategy known as the “rebalance” that the United States has implemented against China.

There are four intentions for U.S. involvement in the South China Sea: first, to not acknowledge China’s sovereignty of the nine-dash line or the territorial sovereignty of the artificial reefs; second, to show their protection of and responsibility toward traditional allies such as the Philippines; third, to curb and interfere with the normal operations of a rising China under the rebalance strategy and to ensure the execution of military reconnaissance and navigation tasks in the South China Sea; fourth, maintaining the face of the U.S. as a global hegemon through an increasingly tough stance against China.

After World War II, in view of the economic difficulties in promoting a regional development structure similar to European integration and the difficulties in establishing a multilateral security mechanism similar to NATO in Asia, the U.S. committed itself to building bilateral and multilateral alliance structures with the U.S. as the center in the fields of economy and security, including Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, the Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand, and including the Trans-Pacific Partnership framework. Such alliances, to a certain extent, certainly contributed to stability and economic development in the region. In June 2012 at the annual Shangri-La Dialogue, the United States proposed the rebalance, shifting its global strategic focus eastward and planning to have 60 percent of U.S. warships deployed in the Pacific region by 2020. When the Obama administration took over, they implemented the new Asia-Pacific policy that would “kill three birds with one stone,” under the “smart power” concept: 1, bind Japan, the Philippines and other countries’ interests and strategic alliances, and push them to the frontline of challenging China; 2, instigate and intensify continuing tensions between China and its neighbors due to territorial disputes and geopolitical conflict, thereby disrupting the construction of a peaceful environment between China and its neighbors and obstructing regional integration efforts in East and Southeast Asia; 3, lockdown the effective projection of Chinese naval power and its effective execution of maritime strategy. The U.S. has repeatedly expressed that it is sitting on the fence on issues of South China Sea sovereignty and territorial disputes, denying direct objectives of curbing China. In reality, it has appeared everywhere in the East Sea and the South China Sea, to the point of barely concealing itself.

The U.S. has gathered a large number of historical and real interests in East Asia, Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific region, so it is understandable that it is unwilling to give them up. China, too, will naturally never give up its sovereignty here. All the while, the United States has on one hand flaunted promoting and maintaining justice and democratic order in the international community, while on the other guided its own actions based on self-interest, to the point of committing acts and speech that totally disregard international justice and order. This is not conducive to the general establishment of global governance and law that’s peaceful, fair and positively-developed, to the building of new international relations that involve win-win cooperation to create a common body for the destiny of humanity, to promote and improve the comprehensive establishment of the existing international order and relations with the U.N. at the center. How the U.S. and China will properly articulate mutual interests and concerns is now the most important matter at hand. Right now, for Washington, the most fundamental thing is that the South China Sea is not the U.S.’s South China Sea. On the South China Sea issue, the U.S. has a famous saying: “Whatever China says, goes.” The reality is that in the South China Sea, the U.S., on its own accord, will definitely say “no.”

The continued back and forth in the South China Sea has become a real and serious issue that cannot be sidestepped in U.S.-China relations. Regardless of whether it is based on the unowned preemptive (first discovered, first to name, the first to develop, the first to administer) due to historical human activity, historical heritage, or to consider international legal documents after World War II and the reality of the geographical origins and other aspects, among other reasons recent U.S. actions in the South China Sea can only reflect the logic of hegemony and power, with no clear legal basis.

Existing U.S. South China Sea policy poses major political and military risks: 1, China will not give up sovereignty claims in the South China Sea, in any form. Confrontation and negativism in the South China Sea will lead to very awkward Sino-U.S. relations; 2, the real intentions of the U.S. are to challenge, provoke, interfere and obstruct, but once the situation spirals out of control, leading to direct military conflict with China, is the U.S. certain of a good ending?; 3, the main claimants to the South China Sea islands such as Vietnam and the Philippines (which are pawns of the U.S.) are not as reliant on the U.S. for security as they are reliant on China in terms of economy and culture. So, is the U.S. able to bear the consequences of a prolonged worsening of the situation in the South China Sea and its periphery?

I think that U.S. actions in the South China Sea are somewhat like the Han Dynasty Huns in northern China, who constantly harassed and plundered the Central Plains. The Han Dynasty, after bearing with them for a long time, eventually swept them towards the northern deserts under Emperor Wu of Han. Just think, if the U.S. does not consider China’s bottom line, is it possible to totally disregard such an end result? The war between the U.S. and China 60 years ago in the Korean Peninsula is not long past. The possibility of a direct confrontation between the two countries due to the South China Sea is relatively small, but if a war does break out, does the U.S. military have full confidence in victory? It’s unrealistic for the U.S. to blindly assume that it is strong and that China is a lamb. Throughout the history of Chinese territorial changes — from the first unification under the Qin Dynasty, through a long period of war between the mighty causing splits and changes and at the peak of the Qing Dynasty — the present-day borders, with the exception of Outer Mongolia, have been consistent. In 1946, the government of the Republic of China recovered territory occupied by Japan based on the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation and other international treaties. The territory of today’s China, which includes sovereignty over the South China Sea, was inherited from the Republic of China, its borders determined since the Qing Dynasty and is a clearly defined territory based on international treaties after World War II. Obviously, unless there is an effective change of international treaties, the legal basis and substantive value of current U.S. actions in the South China Sea are difficult to assess as benign or to forecast positively. For 2,000 years of continuous feudal history, Chinese society has always been constrained by contradictions between the two major opposing camps of the rulers and the ruled, resulting in severe depletion of national capacity and extremely weak comprehensive national strength to the point of almost being bankrupt. But once the nation begins practicing democratic governance and the rule of law, its comprehensive national strength will no doubt grow stronger. Against this background trend, the United States must increase its understanding of Chinese history and characteristics of the Chinese people and adjust its behavior and attitude realistically.

China has always praised a U.S. that is committed to promoting global governance while seeking freedom, fairness, democracy and rule of law, and criticizing American thinking of hegemonism and the narrow worldview of placing its own interests foremost and suppressing the interests and development of other countries. However, the U.S. claims to be committed to long-term global governance while seeking to promote freedom, justice, democracy and rule of law, but obviously always places the interests of the U.S. at the center. This has become the Achilles heel of American global policy, often leading to contradictions between its words and deeds, failing to convince the international community. The current international order requires a strong United States, but the United States should jump out of its narrow line of sight of U.S. interests, and earnestly fulfill an unselfish leadership role of taking on the promotion and maintenance of international social life and development order that increasingly trends towards being comprehensively fair, democratic, lawful and peaceful. It should be said that American leadership in global governance affairs and its “artistic” charm certainly leaves room for improvement. The United States must have a clear understanding and adjust its attitude in a timely manner, be it regarding the South China Sea or global affairs, or on the sustainability of the future development of human society. The exclusion of or hostility to China is very unrealistic, and naturally not conceivable. The U.S. should see China as a good partner for cooperation and positive competition on the road ahead and definitely not an adversary or enemy to be excluded spitefully.

On March 31, when Chinese President Xi Jinping was in Washington to attend the fourth Nuclear Security Summit meeting with Obama, he once again clearly expressed the Chinese government’s clear stance on the South China Sea issue: “China respects and maintains the freedom of every nation to sail and fly under international law, but will not tolerate freedom of navigation as an excuse to undermine China’s sovereignty and national security interests. China will firmly safeguard its sovereignty and related rights in the South China Sea, is firmly committed to maintaining peace and stability in the South China Sea, and is firmly committed to peacefully settling disputes with the nation concerned through direct negotiations.” The root of the problem in the South China Sea is that it must be peacefully resolved through dialogue and negotiation under the premise of respecting the nation concerned and respecting sovereign interests, and that any unilateral, bilateral or third party military intervention or the occurrence of a conflict cannot possibly help to resolve the problem and resolve the dispute, and cannot be the way to resolve the problem once and for all. On the contrary, it can only make the whole situation more complex and deadlocked. The South China Sea is not “terra nullius,” and could never have its legal sovereignty changed through force or unreasonable disruptive behavior. The U.S., on the South China Sea issue, should either respect China and the ASEAN countries concerned acting in accordance with the principles established by the Declaration on Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea and provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea to properly deal with and resolve the territorial and sovereignty disputes between them through peaceful means, dialogue, consultations and so on; or, it should earnestly respect Chinese territorial sovereignty and its upholding of rights and interests which are based on law, and not continue its hegemonic ways of military provocation which are both illegal and extremely unwise, thereby interfering in the South China Sea issue. These two options should be the only choices for U.S. policy on the South China Sea. Otherwise, the U.S., which has continuously created instability in the South China Sea and is stuck in the muck of it, will find it difficult to exclude the possibility of paying a heavy price due to the instability in the South China Sea.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.