The surge in populism can be explained by the relationship between globalization and individual nations. Just like other countries, the United States needs to find another way to respond to this phenomenon than a return to closed borders.

The intelligentsia assured us that based on the invalidity of his proposals, Donald Trump would be stopped last fall. His electoral base would vanish. However, he was still there at Christmas. Then, the primaries began, and against all the expectations of “intelligent” people, he managed to win them one after another. And now, he is the Republican candidate who is expected to face Hillary Clinton (who still needs to defeat Bernie Sanders). A few months ago, it was said that Trump was “a stroke of luck for Hillary,” that she would be able to beat him easily. Now we are starting to doubt that. The hatred for the establishment that Hillary symbolizes, and Donald Trump’s ability to repeat Bernie Sanders’s criticisms of her (the claim that she is the candidate of Wall Street; her fatal free trade policies) give us the chilling feeling that nothing is certain.

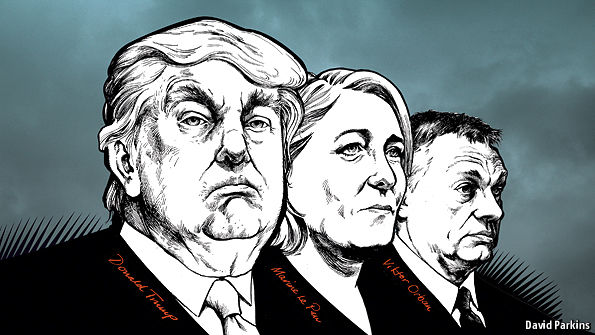

Populism does not put forward any serious ideas, but it is time that we took it seriously, as it is gaining in popularity everywhere. Populism is now at the door of the White House, just as UKIP (United Kingdom Independence Party) might win the referendum on Great Britain’s exit from the European Union. Populist victories in Hungary, Poland and Austria have been attributed to the specific nature of these “small” countries. If the United States and Britain fell to populism, the world would look very strange indeed.

The idea of turning the tables and going for something that has never been tried before may become irresistibly attractive to the people. On a daily basis, we are witnessing alarming backward steps in taking things seriously, in compromise, and in common sense. Is it possible, that someone as unlikely as Trump could soon be governing humanity?

Support for populism has crept up as a result of problems in the relationship between globalization and individual countries. Since the war, the opening up of trade has been extraordinarily beneficial to developing countries and to 2 or 3 billion human beings. In developed countries, free trade has, on balance, been very beneficial. Nevertheless, there have been some losers: medium-skilled workers, employees of low-quality companies, and residents of poorly managed countries, including France, Italy and Greece, but also the Middle East as a whole and, with a few exceptions, Africa. The list is long.

For a long time, the damage has been denied. First, this was because the problems were blamed on technology (that nobody thought to block) and were thus considered to be inevitable. Next, governments, who were incapable of putting in the huge amount of effort required to adapt/transform their economic model, told us that “things will get better.” Paradoxically, the financial crisis of 2008 helped them, as we were then told that we had to wait for growth to resume. The damage would eventually be repaired, everyone would benefit from prosperity, and after a transitional phase, populism would naturally disappear. Everything would go back to normal. It is now obvious that these “wait and see” speeches are not working. The actual (in the U.S.) and imagined (in Europe) demise of the middle classes has quickly attracted people to populism and has fed the revolt.

There has been a complete U-turn turn in the relationship between globalization and states: it is no longer politics that suffers because of the economy, but rather the economy that suffers as a result of politics. The IMF continues to reduce its growth forecasts, international trade has slowed down, and the imbalance in national budgets persists. Monetary policies, which play the heterodoxy card to the max, have run out of steam. Reforms to the financial system have made the banks secure, but have thrown the door to unregulated finance wide open. This has not helped at all: Finance, thanks to its abundance, is still king and is ever more volatile.

A generalized crisis of governance is affecting nations and regional organizations such as the European Union, and is also causing problems on a global level. In developing countries that have not thought to introduce decent anticorruption regulations, progress is being stalled by the delays in adopting democracy. In developed countries, traditional politics have become too big, even though certain countries are better able to cope with them. The problem is that although countries can to some extent absorb the damage, the root of the problem (instability, social dumping, inequality …) has reached global proportions.

Around the world, national governments have been unable to globalize in order to get themselves into a position of sovereignty against economic markets. They have managed to do this with regard to climate change: At COP21, civil organizations and states accepted common restrictions. The same must urgently happen for economic and social matters. The first steps toward an agreement have been taken, such as with the fight against tax evasion, but there is still no consensus on the essential aspects of the problem.

Three political reactions are possible. The first of these is avoidance, an option which is tempting to the left in France, for example. For them, these events are too mundane, and this is not the right time to govern — it is better to protest from the safety of the opposition benches. The second possible reaction is Trumpism and Lepénism (Le Pen is the leader of the French National Front, a far-right party), i.e. a return to the old world of living behind borders. This is not really a viable solution, as the barriers would need to be ever higher, and the hatred would grow ever stronger. Nevertheless, it is gaining ground with the middle classes. The third solution would be a complete ideological rethink of what the roles should be of the state on the one hand, and intergovernmentalism on the other hand, in the new world. So-called “structural” reforms are fairly common on a national level; we need to find out which countries are able to implement them. However, the difficulty remains of making them work on an international level. We need to rebuild Europe and invent a new strategy for global cooperation on currency, trade, taxation, energy, finance and migration. Hillary’s election victory can’t come soon enough — then intelligent people can get to work.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.