The case of a man who committed a shooting in the Bayonne mosque, convinced that the Notre Dame Cathedral was burned by Muslims, has precedents.

That words can poison minds and end up killing has historic evidence. The most recent case occurred in France. A man convinced that the Notre Dame fire was the work of Muslims tried to set fire to a mosque on Monday in Bayonne, in the French Basque country, and shot two worshippers.

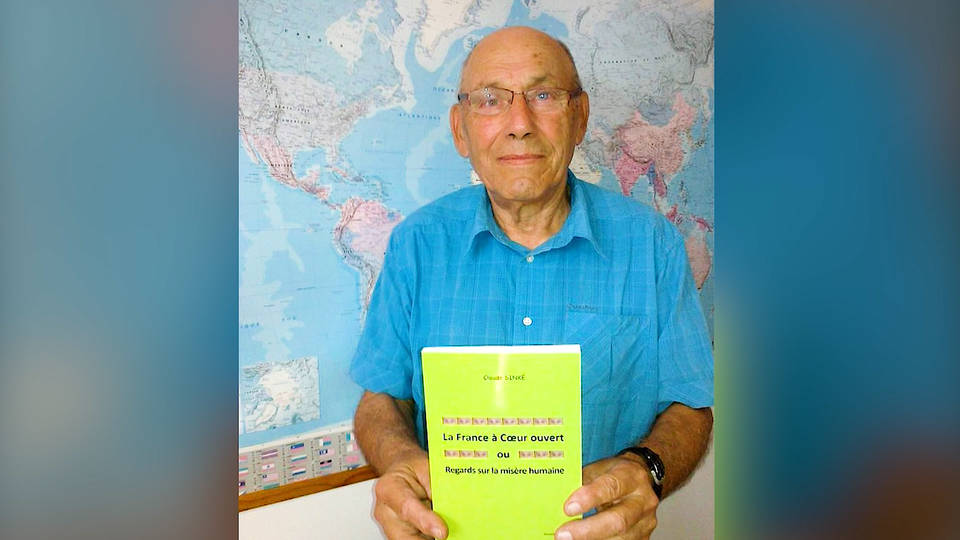

The aggressor, Claude Sinké, an 84-year-old ex-military member with psychiatric problems and an ex-candidate in local elections for the extreme right party, the National Front, attempted to justify the shooting by referring to the conspiracy theory that circulated in the hours and days following the accidental fire in the Paris cathedral. The injured, however, are out of danger.

The Bayonne attack is a good example of how a conspiracy theory, with no factual basis, fed by social media and by politicians in the media, can end up triggering tragedy. Investigators soon discarded the theory that the Notre Dame fire on April 15 was set, but from the first minute, the idea that it could be treated as an attack by Islamic fundamentalists circulated among the extreme right.

“Some sources spoke of two origins of the fire in Notre Dame … If this information were confirmed,. the theory of an accident, posed from the beginning with almost certainty by numerous outlets of the press, even without anyone knowing anything, would be without foundation,” Jean Messiha, the leader of the National Regroupment, heir to the National Front, wrote on social networks the night of the fire. Three days later, the right-wing sovereigntist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan called for an independent investigation. “Power hides something,” he declared.

Limits on resending WhatsApp messages retard, but do not impede, the propagation of false news. None of these politicians mentioned in their theories the hypothesis of Islamic fundamentalism, and Sinké’s act can’t be explained just by the conspiracy theory about Notre Dame. But it would not be the first time that someone decided to dispense justice with their own hands based on a falsehood.

A recent case in 2016 is that of what was called Pizzagate—an unfounded rumor that a pizzeria in Washington, D.C., frequented by neighborhood families, was actually the facade for a network of child traffickers in which Hillary Clinton, Trump’s rival in that year’s presidential election, was involved. A man who strongly believed in the rumor went to the pizzeria armed with a rifle and fired several shots without causing casualties.

This episode was a warning about what happens when someone decides to take action based on conspiracy theories. This is not new. “Historically conspiracy theories are linked to violent behavior at a minimum since the Middle Ages,” wrote psychologists Pia Lamberty and David Leiser in a study about the connection between these theories and violence.

Not every conspiracy theory necessarily leads to violence; in fact, the majority are inoffensive. “Conspiracy theories are very widespread among the population. More than half the population believes in some conspiracy theory. It would be strange if all those people were violent,” said Sebastian Deguez, a researcher in cognitive neuroscience at the University of Friburg, Switzerland and author of the book “Total Bullshit: At the Heart of Post-Truth.” But he added that “in some cases” one sees “a certain disposition” toward a justification of violence because “if they already don’t believe in the democratic virtues and methods; if they believe that the game is rigged, that things are hidden from them, that they are dominated,” thus, he concluded, “violence is justified.”

Cases such as Pizzagate and that of Bayonne, involving isolated people, perhaps fragile and easily influenced, “raise an interesting question,” said Deguez. “Many people believe that the Notre Dame fire was not an accident, but that belief was just a subversive stance that served to show that someone didn’t want to be used by the authorities. But that’s it. These people do nothing. The proof that it is more about a stance than a belief is that few people try to act and to go further.”

The list of violent conspiracists could include the man who in 2011 killed six people by gunfire and wounded a congresswoman in Tucson, Arizona, who believed that the 9/11 attack was a government plot. And the terrorists who in March and August 2019 respectively carried out the killings in Christchurch, New Zealand and El Paso, Texas. The two were inspired by the racist theory of the grand substitution, according to which the white native population is being substituted by foreigners and other religions.

“A most important phenomenon are the multiple terrorist groups with conspiracy theories included in their fundamental beliefs,” wrote the journalist Jonathan Kay, who investigated American conspiracies in the book, “Among the Truthers.”* He mentioned the example of the fundamental charter of Hamas, which cites as its source the authority of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,”** a fabricated foreign conspiracy text, which a good part of twentieth century anti-Semitism used to support its views.

“If we look at radicalized groups, they are where conspiracy abounds,” states Deguez. “It is like a motor that allows the group to unite, justifying its existence and its actions, its violent methods. A conspiracy theory provides at the same time a justification and a motivation to act undemocratically.”

*Editor’s note: This quote, accurately translated, could not be verified.

**Translator’s note: Protocols of the Wise Men of Zion (also known as The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion) is an anti-Semitic forgery purporting to be a record of meetings of Jews plotting world domination.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.