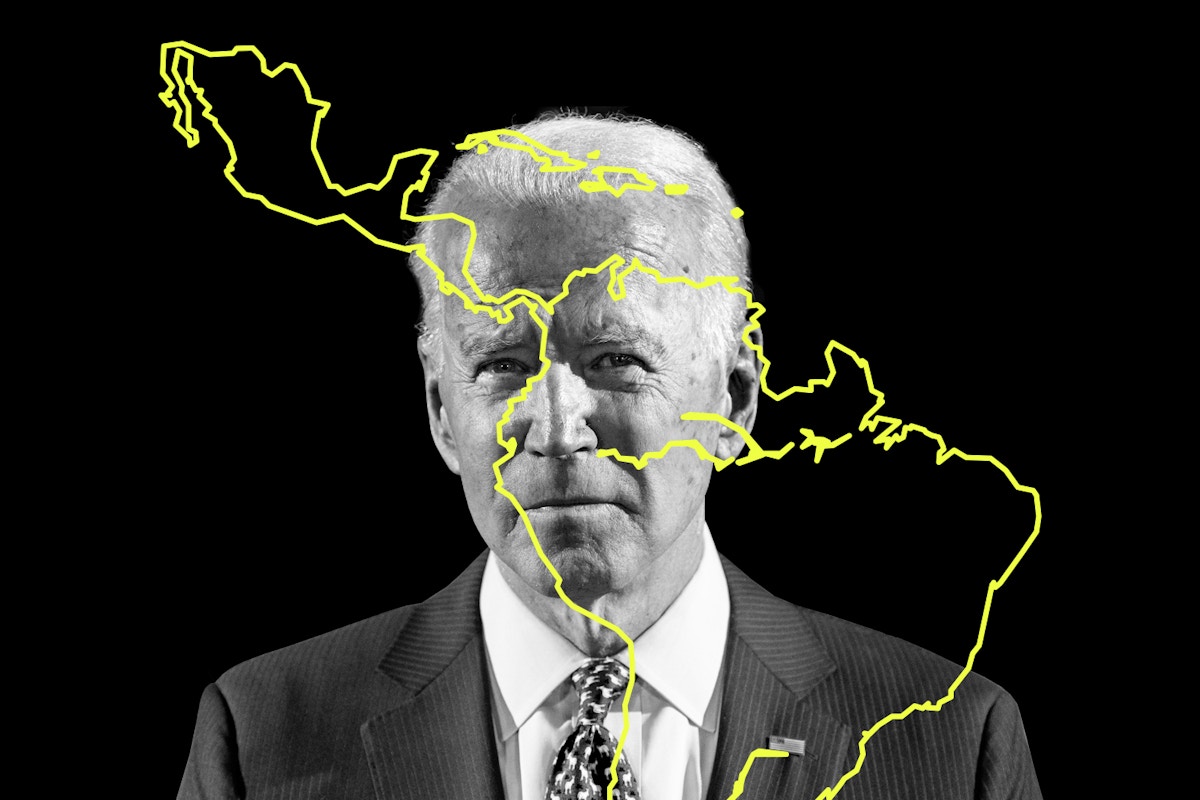

During the Obama administration, the current United States president, Joe Biden, acted as Barack Obama’s deputy, participating in adjusting Latin American policy. With the arrival of Biden in the White House, the traditional and pragmatic Democratic Party will reenter the U.S. political arena, and policies related to the United States’ backyard will enter a new period of adjustment as a result. It can be predicted that U.S.-Latin American relations during the Biden era will not undergo major changes generally, but there will be two significant changes in some parts, evolving in the complicated direction of reconstruction and diversification.

During the Trump administration, Obama’s Latin America policies were entirely upended, especially by raising a big stick toward radical left-leaning countries and categorizing Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua as the “troika of tyranny.” Donald Trump also recognized Juan Guaido as the president of Venezuela. He reversed policies regarding Cuba; soon after taking office Trump announced the cancellation of nearly all the Obama-era policies easing relations with Cuba. Before he stepped down, he did not forget to put Cuba back on the list of state sponsors of terrorism.

However, the extreme blockade against Cuba not only had little effect, but also prompted old forces in Cuba to band together against the U.S. With Biden in office, the U.S. may once again soften its stance on Cuba and pursue a strategy of engagement. U.S.-Cuba relations will tend toward moderation, and it is expected that restrictions on American travel, remittances, finance and trade with Cuba will be loosened. Cuba may also be removed from the list of state sponsors of terrorism. Similarly, for Venezuela, the Biden administration is unlikely to rush to the forefront in support of the opposition party’s efforts, but will instead use the international ally system against Venezuela.

After Brazil’s President Jair Bolsonaro took office, he changed the left-leaning government’s policy of gradually distancing from the U.S. and instead turned entirely toward Trump, closely following the foreign policy agenda of the U.S. Trump returned this favor, using both false claims and the truth to produce many benefits for Bolsonaro and bringing U.S.-Brazil relations closer. With Biden in power, U.S.-Brazil relations may enter a period of reconstruction. Although Bolsonaro said in his message congratulating Biden on his election victory that he hopes to continue strengthening the U.S.-Brazil alliance, promoting trade cooperation between the two countries and defending democracy and freedom, Bolsonaro’s ideas on climate change, multilateralism and other issues differ greatly from Biden’s. Such differences are difficult to overcome in the short term. Biden has made it clear, and Bolsonaro should recognize, that if Brazil cannot act as a responsible guardian of the Amazon rain forest, the U.S. will initiate joint international actions to adopt trade restrictions and sanctions to ensure that the region is protected. Bolsonaro responded that he has no intention of using such fiery rhetoric, but the other party needs to recognize Brazil’s strength. This war of words indicates that future U.S.-Brazil relations may enter a period of fine-tuning and adjusting. However, in light of the status of the two countries in the world and in the Americas, they cannot maintain a rigid stalemate and will instead seek a common point of interest in the midst of conflicting interests.

Although Biden disclosed before taking office that he would correct Trump’s foreign policy, the revisiting of his Latin American policy will inevitably serve the overall strategic interests of the U.S. and the security interests of the Western Hemisphere. The two U.S. political parties have reached consensus on some fundamental strategies, and these cannot be changed.

First, the tradition that the Latin American backyard is not a priority consideration for U.S. global strategy will remain unchanged. Latin America has never been the focus of U.S. global strategy. Based on geopolitics the U.S. is confident that since Latin American geopolitics, history and culture have naturally close ties to U.S. traditions, it would be extremely difficult for another major power to replace it. Additionally, many Latin American countries have already begun the process of democratization and their political distancing is within a controllable range. The Indo-Pacific, Middle East and Atlantic alliance systems remain the top priorities of the U.S. global chess match. Therefore, although the Biden administration may someday increase investments in and pay more attention to its backyard, Latin America will not rise in the ranks of the U.S. global strategic agenda.

Second, the U.S. aim of suppressing radical left-leaning countries in its backyard will not change. Although the Biden administration may reduce the intensity of its pressure on radical left-leaning countries in Latin America, the methods by which this suppression is carried out will grow more diverse. In order to ensure the safety of Latin America, the Biden administration may use less hard power and more soft power, coupling strength and gentleness to eliminate radical anti-American regimes and clear a path for American control of its backyard. Thus, the Biden administration will not abandon the “Color Revolution” against Cuba and Venezuela, the axis states of the anti-American Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America. The administration will continue to exert pressure on these left-leaning powers to push for human rights, democracy and good governance, and will list the countries of this alliance as a national security threat to the U.S. The Biden administration may once again break the ice of U.S.-Cuba relations, showing goodwill in the international community, but it will not completely melt the ice with Cuba. Such pleasing rhetoric as “equal partnership” and “shared responsibility” will resurface, while at the same time the strategies of supporting with one hand while striking with the other and dividing to conquer will not change.

Third, the redline strategy of preventing foreign powers from encroaching on the U.S. backyard will not change. Although Latin America is not a priority consideration for U.S. global strategy, the bottom line remains that other major powers cannot gain influence in the region. Although Biden and Trump have conflicting political views, Biden will not reverse every Trump decision. It is likely Biden will continue Trump’s initiative of pursuing American growth by increasing control over its backyard, preventing China and Russia from gaining influence over the development process in Latin America. Washington will not be happy to see China and Russia becoming new neighbors of the U.S. and certainly will not tolerate Latin American countries playing the China or Russia card to subvert American influence and control over its backyard. The specter of the Monroe Doctrine will continue to linger in Latin America.

Fourth, the primary argument in U.S.-Latin American relations of control and opposing control will not change. In recent years, along with changes in the political environment in Latin America, some countries have views inconsistent with the U.S., which complicates relations. There are vague feelings of distance but not separation, and entirely conflicting ideas of opposing the U.S. and staying close to it. Although such relations are complex, building a secure barrier in its backyard is the unchanging strategic position of the U.S. toward Latin America. Although the variability and increments of U.S.-Latin American relations are determined by the changing political landscapes of both sides, the U.S. has always been the driving force in changing these relations. Dependence and autonomy, control and opposing control are all common themes of U.S.-Latin American relations.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.