A genuinely fascinating exercise is analyzing the “new Cold War” and its similarities and differences compared to the previous one (or ones). Gradually, this concept is becoming widely accepted concerning the current international situation.

The U.S., for example, has openly admitted for the first time that relations with Beijing resemble precisely a new version of the Cold War. Until recently, everyone denied this interpretation. In general, the typological features of this type of confrontation, particularly of its current form, are a diverse topic and are subject to different interpretations. However, one feature is undeniable: The speed with which events develop and phases of relationships alternate. This dynamic is incomparable with what came before.

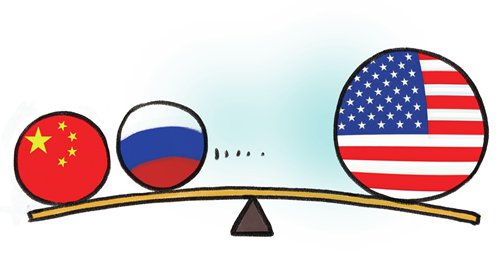

The beginning of this summer was a time of restructuring, in a manner of speaking. According to the plan of American strategists, the chaotic and rather multidirectional conflict is being replaced by a much clearer confrontation. It is modeled on the Cold War of the second half of the 20th century, meaning a comprehensible division of the world into two camps. Those camps are familiar — a free world against an unfree world. The rebuilt old collective political West against the newly constructed collective East.

Joe Biden’s administration has set a goal to systematize the surrounding anarchy of international affairs, which the U.S. finds unbearable to exist in.

The difficulty of systematization lies in the increased heterogeneity of the potential blocks. The leaders of the liberal world order — the U.S. and Europe — do not share pragmatic interests, and the “community of autocrats” exists rather in the imagination of its opponents than in reality. Therefore, merely identifying and summoning the adherents of a given ideology to form a united front will not work. In any case, ideologies can hardly be traced now, unlike the ideological rigidity during the 20th century.

For the sake of fairness, the very formulation of the task is not absurd. It does not make it right, however. The Biden administration is consistent. It set out to systematize the surrounding international anarchy, which is sickening for the U.S., having become accustomed to the position of undisputed leader in the last several decades, first in the New World, then everywhere.

The world order crisis began long ago, at least from the early years of the 21st century. Still, it has become defiant in recent years thanks to the style and approach of Donald Trump. Biden positions himself as the antithesis of his predecessor, and in many ways, he is. But this does not mean either a rejection of everything done in the previous four years or a return to pre-Trump policies. While not rejecting the “rivalry between the great powers” narrative that has been declared the basis of American strategy under Trump, Biden believes in the necessity of a more thorough approach. This is precisely what the classic Cold War schemes are for, especially considering the U.S. and its allies won it. Hence, the desire to revive the black-and-white picture, rallying like-minded people. This rallying is important not so much for the strengthening of America itself, but for avoiding as much as possible any obstacles associated with the independent actions of close partners.

But given the aforementioned heterogeneity in the ranks of the allies, a convincing adversary is needed to rally against. Separately, neither Russia nor China is currently playing this role. It is not easy to scare the Europeans with China or the Americans with Russia, despite widespread efforts. But as a two-headed dragon, Beijing and Moscow can form a rather formidable image for both the American allies and the wavering neighbors of both powers.

The encouraging results of the Putin-Biden summit are precisely the structuring part of the process, reducing risks in the most dangerous areas of interaction between the countries.

A detailed analysis of possible strategies for the “new Cold War” has begun, and different options are being offered. But a common argument unites those various assessments — an increase in tension is inevitable. Suppose a structured confrontation is recognized as a way out of a dangerous and highly unbalanced international situation. In that case, it means that it will worsen. Neither can we forget about the acute domestic problems of all major players, where foreign policy is now boldly used to solve them. In this sense, the encouraging results of the Putin-Biden summit do not contradict the general logic. On the contrary, this is precisely the structuring part of the process, reducing risks in the most dangerous areas of interaction. The action of the British HMS Defender destroyer in the Black Sea is also a provocative act that maintains the intensity of the conflict. In this context, it does not matter whether it was London’s decision, or an operation coordinated with the allies. This is a dialectic of the same phenomenon.

We must be ready to both maintain a dialogue on the first line of defense and put an order for a confrontation. Likewise, we must accurately respond to the manifestations of the second line of defense, which is a constant testing of the capability to act. Salvation, let us hope, is in the fact that now, time passes quicker than ever. What used to take decades now takes years. And years turn into months. This does not diminish the risks. Conversely, in such a concentrated environment, the price of each action increases. But if the specifics of the 21st-century red lines are understood, there is a hope to break out of the current turn of events faster than from the past ones — even if some red lines are similar to those of the past, and some are entirely different.

Be that as it may, there is more clarity in the international situation now than a couple of months ago. And this is already a step in the right direction.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.