One Transatlantic Spat Closer to European Independence

Is Washington mistreating its European allies by cutting British Aerospace out of the Joint Strike Fighter program? According to this op-ed article from France's Le Figaro, Europeans should get the message from this latest insult, and focus on the 'strategic independence of our continent.'

By Alexandre Adler

Translated By Pascaline Jay

March 23, 2006

Le Figaro - Home Page (French)

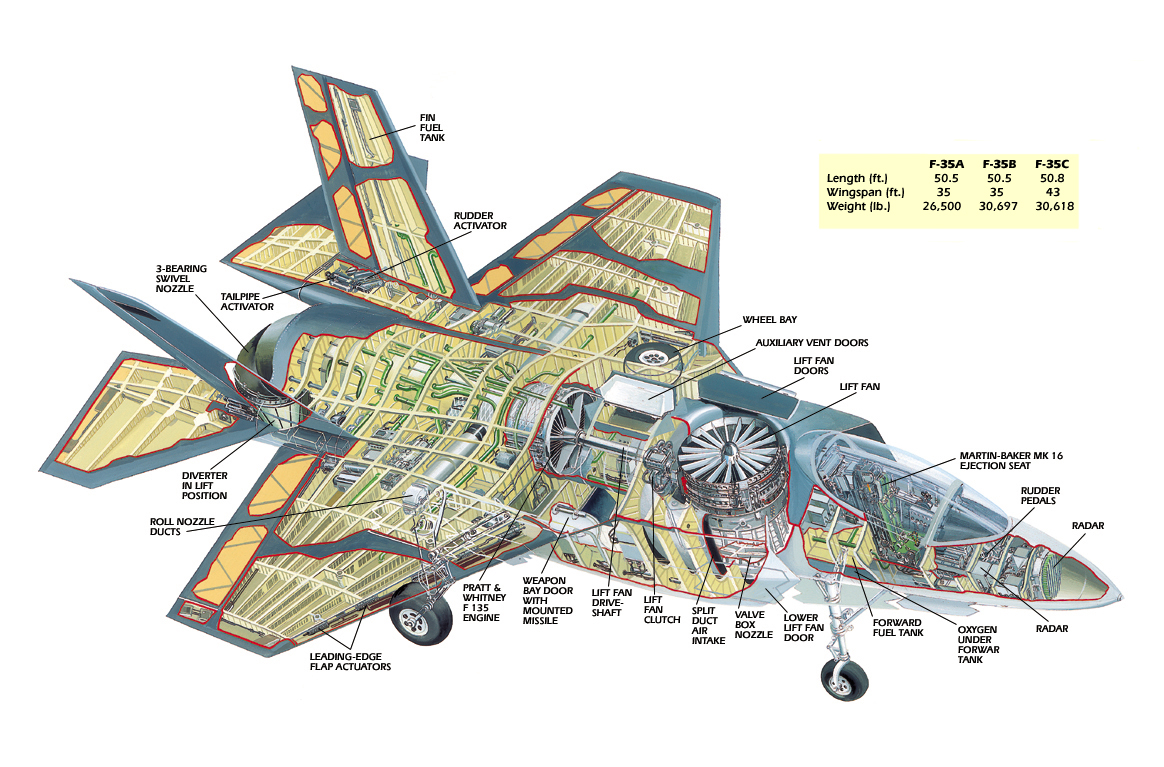

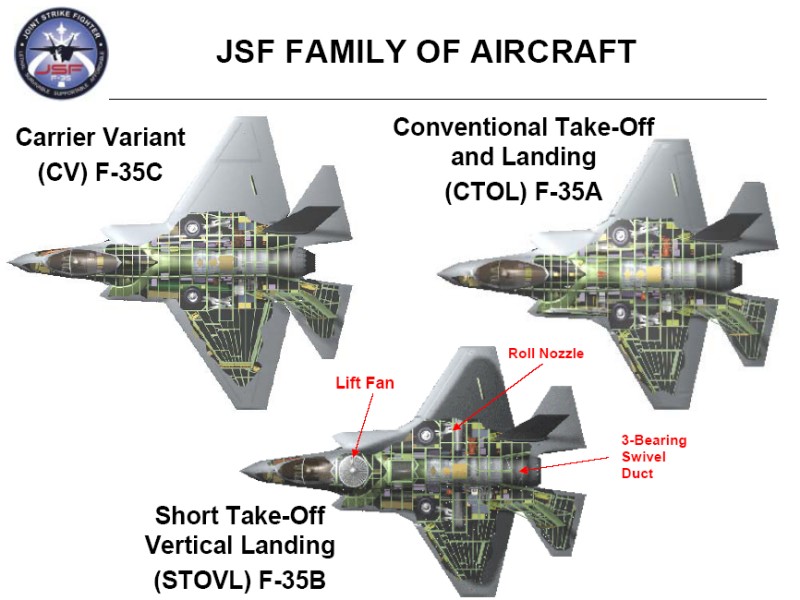

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is a Military Fighter Aircraft

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is a Military Fighter Aircraft

Designed By The United States and The United Kingdom.

It is Intended To Replace the Current Generation of Strike

Fighters. There are Three Levels of International Participation

in the Project, with the British Alone in Level One.

[ Joint Strike Fighter]

Joint Strike Fighter]

[CLICKABLE PHOTO BELOW]

.JPG) The British-Designed Thrust Vector Engine, which Allows

The British-Designed Thrust Vector Engine, which Allows

the JSF to Fly Vertically and Horizontally. (above);

A JSF Prototype Takes Off

Like a Helicopter - Straight Up. (Below)

Diagram Represents the Surviveablity of the JSF. (above)

Diagram Represents the Surviveablity of the JSF. (above)

Let's commence with the symptom, which seems so obvious that up to

the present, it hadn't sparked the analysis that it deserves. The United States,

through the will of the Pentagon, has purely and simply dismissed their

British, as well as their Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, Italian and Turkish

partners, from the next step in a program to build a new fighter-bomber, the "Joint

Strike Fighter," JSF.

Initially conceived for the U.S. Air Force and Navy, the JSF was

rapidly adopted by the British as their future combat plane, and so, British

Aerospace, which had just refused Tony Blair's plans for an industrial alliance

with Germany, was involved from the start in the conception of the engine and

other high-technology components.

Of course, this arrangement didn't please everyone, including, among others

the American aeronautics giant Boeing McDonnell Douglas [recently merged]:

indeed, on the commercial market, this company is facing a formidable adversary,

Airbus, of which British Aerospace is a principal shareholder. It is a fact

that the civilian aeronautics industry is particularly subject to the

uncertainties of the business cycle, whereas the defense industry depends

solely on State orders and sales, which gives it remarkable stability.

In the current competition, the American aerospace lobby doesn't

want U.S. taxpayers to finance, through British Aerospace, the accounts of

Airbus. But up to the present, these considerations, to which Defense Secretary

Donald Rumsfeld is particularly sensitive, couldn't compete with the

Transatlantic expediencies of State. According to the U.S. State Department,

and until very recently, the White House, London and its closest European

allies, maintaining allied fidelity was worth a few more billions for Airbus.

But suddenly, the picture has changed, and here is President Bush,

sacrificing without scruples the "special relationship" with London

that Roosevelt initiated with Churchill in 1941, that Kennedy revived with

MacMillan - against Gaullist seductions - in 1961, and that finally, the victorious, morganatic marriage [marriage between

high-born and commoner] between Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan.

And now a leak from the State Department allows us to see behind the curtain. In a letter that should never have been made public,

President Bush exhorts his friend and ally Tony Blair to stand firm on the

Iranian crisis. We have also learned that London had planned to offer Teheran

some added incentives in exchange for an extension of its commitment not to

enrich uranium, and reading between the lines, that London, under these

conditions, was totally in favor of Russia's proposition to proceed to the

enrichment of the uranium outside the territory of the Islamic Republic.

If we take this line of reasoning further, one will

recall that this political overture with Teheran was a particularly dear

project to the British. It is even possible that differences between the appraisals of London and Washington on this point went even deeper, when the two allies

inevitably discussed the extent of possible retaliation, in the case of an

escalation of the Iranian nuclear crisis.

In contrast to London's optimism, one finds in fact Israel's

intransigence, which is completely understandable. It is well known that the

Pentagon in general and more precisely Donald Rumsfeld, are quite susceptible

to the Israeli point of view, and are often irritated by the procrastination of

the British. On this very subject, we can also consider a low-level battle

between Condi Rice's State Department and Vice President Cheney at the

Pentagon.

Right now, in a striking parallel between Washington and Teheran,

we can see the "doves" on both sides, Condi Rice and Rafsanjani,

overseeing a reluctant dialogue between the two parties on the future of Iraq,

in which both sides must fight together to preserve Baghdad's Shiite

government. But London's decision to favor the partisans of negotiation has certainly

cost it dearly.

It is a near certainty that the United States considered Tony

Blair the only left-leaning guarantor of the Transatlantic Alliance, and that

the decline in his influence, combined with the pacifist maneuvering of his

Chief of Diplomacy, Jack Straw, a former communist, is what made it impossible

for Great Britain to take part in the JSF project.

The circumstances of this present quarrel are sure to change;

but if other European countries finally grasp the importance of this crisis, it

is that the strategic independence of our continent, relying on a

London-Paris-Berlin triangle, without pondering utopia, may finally be

conceivable.

French

Version Below

Une

nouvelle brouille transatlantique?

23 mars

2006, (Rubrique Opinions)

Commençons

donc par le symptôme, qui semble tellement énorme qu'il n'a pas donné lieu,

jusqu'à présent, à des analyses à la hauteur de l'événement. Les Etats-Unis,

par la volonté du Pentagone, ont en effet purement et simplement congédié leurs

partenaires britannique ainsi que néerlandais, danois, norvégien, italien et

turc dans la poursuite du programme de réalisation d'un nouveau chasseur

bombardier connu en anglais sous le nom de «Joint Strike Fighter», en initiales

JSK.

Conçu

initialement pour l'armée de l'air et la marine, le JSK avait été rapidement

adopté par les Anglais comme leur futur avion de combat, et, dans ces

conditions, British Aerospace, qui venait de refuser à Tony Blair toute

alliance industrielle avec l'Allemagne, fut dès l'origine associé à la

conception du réacteur et d'un certain nombre d'autres éléments de haute

technologie.

Cet

arrangement ne faisait évidemment pas la joie de tous, et notamment du géant

américain de l'aéronautique Boeing Mac Donnell Douglas : ce dernier, en effet,

rencontre sur le terrain commercial un formidable adversaire, qui n'est autre

qu'Airbus, dont British Aerospace est par ailleurs l'un des principaux

actionnaires. On sait que l'industrie aéronautique civile est particulièrement

soumise aux aléas du cycle économique, tandis que l'industrie de défense, elle,

ne dépend que des commandes de l'Etat et de ses ventes, ce qui lui confère une

remarquable stabilité.

Dans la

compétition actuelle, le lobby aéronautique américain n'a pas envie que

l'argent des contribuables des Etats-Unis finance, à travers British Aerospace,

la trésorerie d'Airbus. Mais, jusqu'à présent, ces considérations, auxquelles

le ministre de la Défense Donald Rumsfeld est particulièrement sensible, n'ont

pu l'emporter sur la raison d'Etat atlantiste. Pour le département d'Etat et,

jusqu'à tout récemment, pour la Maison-Blanche, la fidélité de Londres et de

ses alliés les plus proches en Europe valait bien quelques milliards de plus

pour Airbus.

Tout d'un

coup, le paysage change, et voici que le président Bush sacrifie sans états

d'âme cette «relation spéciale» avec Londres qu'instaura Roosevelt avec

Churchill en 1941, que relança Kennedy avec MacMillan en 1961 contre les

sirènes du gaullisme et que fit triompher enfin le véritable mariage

morganatique de Margaret Thatcher et de Ronald Reagan.

Or une

fuite en provenance du département d'Etat nous permet de lever un coin du

voile. Dans une lettre qui ne devait pas être rendue

publique, le président Bush exhorte son ami et allié Tony Blair à rester ferme dans

la crise avec l'Iran. On apprend au passage que Londres avait envisagé d'offrir

à Téhéran quelques pourboires supplémentaires en échange de la prolongation du

non-enrichissement de son uranium, et entre les lignes que Londres, dans ces

conditions, devait être tout à fait favorable à la proposition russe de

procéder à l'enrichissement de l'uranium iranien en dehors du territoire de la

République islamique.

Si on

prolonge encore la réflexion dans la même direction, on se rappellera que la

politique d'ouverture avec Téhéran était un projet particulièrement cher aux

Britanniques. Il n'est pas impossible que les différences d'appréciation entre

Londres et Washington sur ce point soient allées plus loin encore lorsque les

deux alliés ont inévitablement discuté de l'ampleur des représailles

envisageables, en cas de montée de la crise nucléaire iranienne.

A l'opposé de l'optimisme de Londres, on trouve en effet l'intransigeance,

elle-même tout à fait compréhensible, d'Israël. Et on sait que le Pentagone en

général et Rumsfeld en particulier sont très sensibles au point de vue

israélien et souvent irrités par les atermoiements britanniques. On peut aussi

considérer que, sur ce dossier lui-même, une lutte sourde oppose le département

d'Etat de Condie Rice au vice-président Chesney et au Pentagone.

Dans un

parallèle saisissant entre Washington et Téhéran, on voit, en ce moment même,

les «colombes» des deux camps, Condie Rice et Rafsandjani, imposer un

dialogue réticent entre les deux parties sur l'avenir d'un Irak où les uns

comme les autres ne peuvent que lutter ensemble pour préserver le gouvernement

chiite de Bagdad. Le jeu de Londres en faveur des tenants de la négociation lui

a sûrement valu une rebuffade de taille. Peut-être aussi certains, aux

Etats-Unis, considèrent-ils que Tony Blair était le seul garant à gauche de

l'Alliance transatlantique et que le déclin de son influence, combiné aux

menées pacifistes de son chef de la diplomatie, Jack Straw, cet ancien

communiste, ne valait pas la participation aux JSK. Les circonstances de la

brouille ne seront évidemment pas durables ; mais si les autres Européens

prennent enfin la mesure de cette crise, c'est l'indépendance stratégique de

notre continent, reposant sur un véritable triangle Londres-Paris-Berlin, qui est

peut-être enfin envisageable sans utopie.