The musician will play eight Spanish cities and put on a big concert in Paris in which he reclaims his classics.

After starring in the artistic vanguard of the 20th century, an elderly Pablo Picasso set himself up in a studio on the Côte d’Azur to pore over the work of the masters who had made their mark on him: Rafael, Velázquez, Delacroix, Manet and Goya. He painted them in his own style and created versions of his own most celebrated works as if painted by them. He ended his days immersed in his world, as if painting – as reason, as art, as a way of connecting with the world, as human debt – defined his whole existence. Soon to turn 78, Bob Dylan, one of the most influential musicians of the last century, favors the same philosophy. He will end his days like Picasso.

Almost an octogenarian, with aches and pains in their gentle, sometimes comical, way, Dylan is facing the last phase of his life. The stage is his studio and it’s not on the Côte d’Azur. His studio is an ever-changing space, constantly evolving, sometimes described as the “Never Ending Tour.” It’s his workshop, which could as easily be a big city as a small town off the beaten track for most stars. And so, while the never-ending tour may have passed through Salamanca, Madrid and Barcelona last year, at the end of this month and the beginning of the next, it will visit Pamplona, Bilbao, Gijón, Santiago, Seville, Fuengirola, Murcia and Valencia. Last night it reached Paris, where he also played on Thursday, and where he’ll play again tonight.

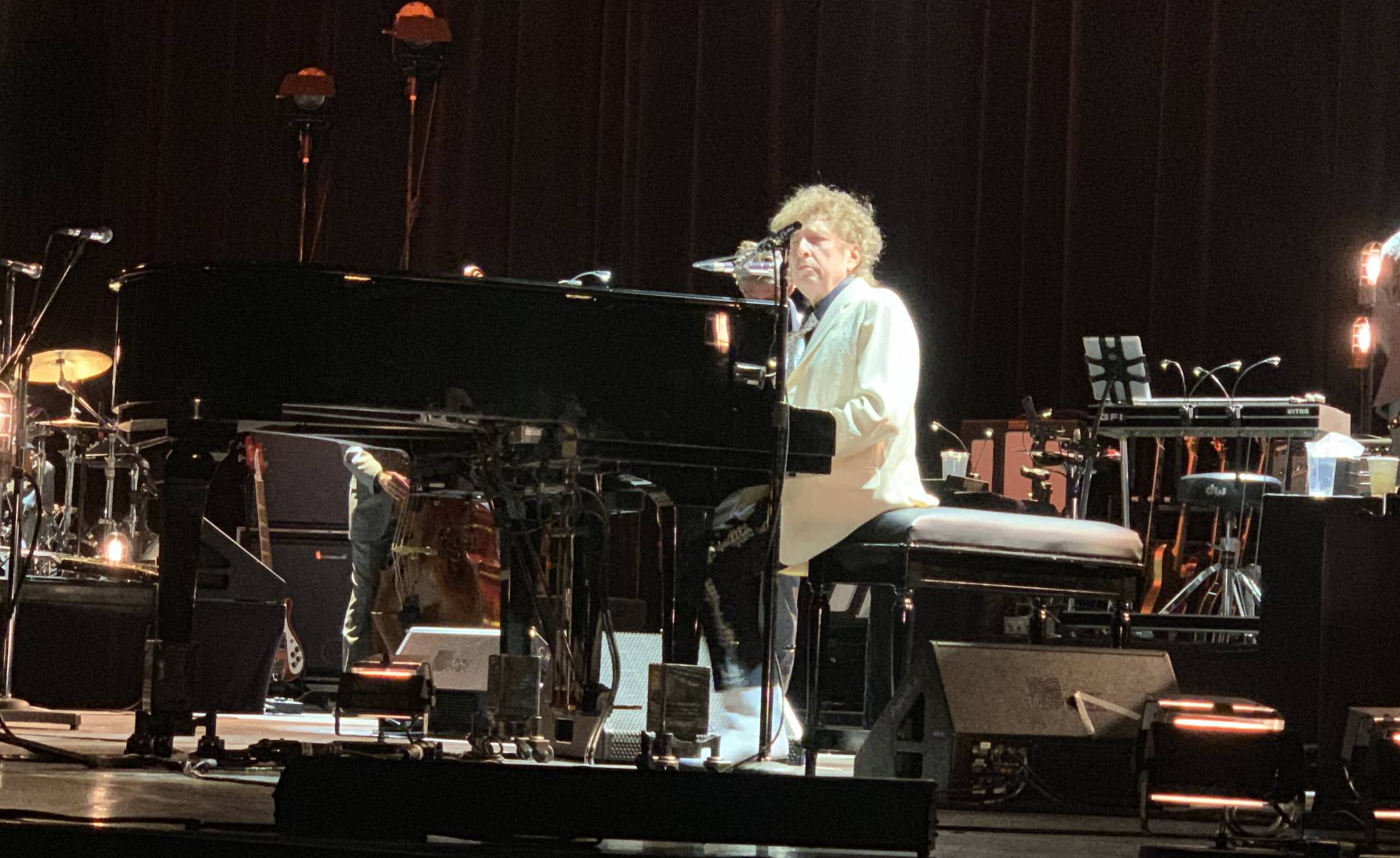

Underneath the starry ceiling of the Grand Rex, a wonderful art deco movie theater built in the early 1930s, Dylan and his band appeared suddenly out of the darkness. The lights fell, and when they returned, the five members of the band were already onstage, as if dropped from heaven, or risen from the bowels of the earth. The band in gray suits, Dylan in a sparkling sequined white jacket, black trousers with broad gold stripe, and white boots. The lights returned at the very same moment they launched into “Things Have Changed,” a song the American musician has recently opened shows with. It is a veiled declaration to his audience that things have changed, even if he still maintains the same approach with regard to his legend in his own lifetime. No greeting, no chat, no singing classic songs as they were recorded. Dylan changed such a long time ago he doesn’t remember himself how he was before.

Perhaps at the same time that he’s experiencing this last phase of his artistic life, the same is happening to his life as a whole. After playing more than 100 concerts a year, all that’s left for Dylan is to die on stage, in his own private workshop in front of everyone, where, so long as no illness or mishap cuts everything short, he’ll play his swan song like Picasso, surrounded by his masters, creating versions of his most famous canvasses. Versions like “Highway 61 Revisited,” which assaulted the night like a horse gaining ground as it gallops round a bend. Unexpected and forceful, with a savagely reverberating drumroll. George Receli is an exceptional drummer, a thoroughbred of powerful strokes who could start his own school on the basis of his shimmering shapes on “Love Sick” and the person who rescues Dylan and his rusty voice when he’s unable to scale the highest peaks, peaks he reached with sharp tenderness and incredible ease as a young man.

Last night, echoes of another time were faintly heard when he sang “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” the night’s weakest moment. The poetic force of Dylan’s ever imperfect voice changed some time ago into a limited crowing; damaged, but which sustains itself on an urgent need to cut through, to bite despite its age. The tone has lost some of its sting and detail, but a strange air of suffering has been gained, like an era reaching its end but still looking forward. As he did in “Like A Rolling Stone,” performed in a style akin to gentle swing, Dylan varies the song’s meter with the complicity of his magnificent band, adapting it to his final voice, the most ancient, the most unfriendly, the only one that can outsmart his own legend and turn it on its head. He’s taken off Frank Sinatra’s suit, stripped American standards from the repertoire, and introduced his own classics – so popular, so changed.

It’s the myth of the elusive man, now obsessed with his masters. The wealth of sound that defines the band, presided over by Dylan on piano, catches the threads of North American grassroots music and weaves them into a whole. An absorbent whole, containing sublime moments as in “Scarlet Town,” “Early Roman Kings,” “Thunder on the Mountain,” “Soon after Midnight” and “Gotta Serve Somebody.” He takes these pre-rock ‘n’ roll sounds (country and western, R&B, folk, swing and blues) and injects them into his songs, transforming them into the same conceptual discourse, whether it’s the legendary “Blowin’ in the Wind” or the energetic but far less famous “Pay in Blood.” In order to redefine his work, he’s fueled by these explorations of the pioneers who made their mark on a teenage Robert Zimmerman listening to late night radio shows in his Minnesota hometown in the 1950s, and who gave shape and significance to the definitive rock ‘n’ roll, the musical vanguard that would transform the 20th century, turning it into something more fun, tolerant and open.

Like Picasso, Dylan, who played the moving “When I Paint My Masterpiece,” is in the last phase of his life, surrounded by his masters. He’s already said in the scant interviews he’s given this century that all his imagery comes from there. A composer of an incomparable songbook, a universe in its own right, Dylan has been through different stages, and each important stylistic change has ended up becoming a movement with seismic connotations for the medium of popular music. Because of this, musicologist Paul Williams, one of the most renowned Dylan biographers and founder of the music magazine Crawdaddy, called him “the Picasso of music.” Nowadays, the American musician doesn’t make such major waves, though his singularly resonant take on traditional American music is an idea of value. (And who knows if it’s proving influential to a young musician of the future and “freak” of antisocial temperament.) The American musician perhaps awarded the best moment of the night to “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” on piano and harmonica (heard on some songs for the first time in a long time).

Spiritedly blowing the instrument with which he made his name half a century ago, Dylan, illuminated by a simple orange light amid the darkness, cut through the night singing some of his most celebrated lines, a song that could easily be about himself, his relationship with the public and with history: “So long, honey babe / Where I’m bound, I can’t tell / Goodbye’s too good a word, babe / So I’ll just say fare thee well.” After the intensity of the harmonica, the song overwhelmed the theater with the starry sky. A powerful, broken melancholy seized the night. The audience rose out of their seats and scores crowded the aisles and front rows during the encores. After playing “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” Dylan walked off without saying goodbye while the band played on. Goodbye’s too good a word, babe. All those who believe in his music, as well as his detractors, and even those indifferent to him, ought to know one thing: Bob Dylan will not be present at his own funeral.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.