A four-month delay separates the presidential inauguration of Joe Biden on Jan. 20 and that of the new president of Ecuador. As we do not know whom we will choose, what we are thus able to anticipate from the bilateral relationship centers on what can be expected from Biden.

President Donald Trump dusted off the Monroe Doctrine. With Venezuela, he toyed with the idea of a potential invasion; this was illusory given that it would never have received the backing of his military forces. With Cuba, he turned his back on Barack Obama’s gestures toward a rapprochement. He also struck a hard line on the immigration problem: Immigration authorities separated 666 children from their parents along the Mexican border; today, they do not know to whom they should be returned.

On the positive side, Trump announced his proposal to foster conditions so that American companies with factories currently located in Asia, and especially China, could relocate them to South America. However, this initiative only dates from this year, and in light of the change of government, it is a dead letter.

The foreign policy of a small country vis-à-vis the dominant regional power must orient itself around the principle of achieving the biggest gains possible. In the latter stages of its mandate, since the previous ambassador, José Valencia Amores, became the minister of foreign affairs, the Ecuadorean government has carried out an impeccable foreign policy. Trump has been consistent in Ecuador: He named various high-ranking career diplomats as ambassadors in Quito, and he contributed to the International Monetary Fund, giving Ecuador the green light on a loan worth $6.5 billion, of which $4 billion has already arrived and without which the fiscal outlook would be complete chaos.

With Trump, Ecuador was able to chart a smooth passage to the Generalized System of Preferences,* thereby allowing our flower growers to compete on an equal footing with Colombia in the U.S. market; it also negotiated the first stage of a prospective trade agreement with Washington.

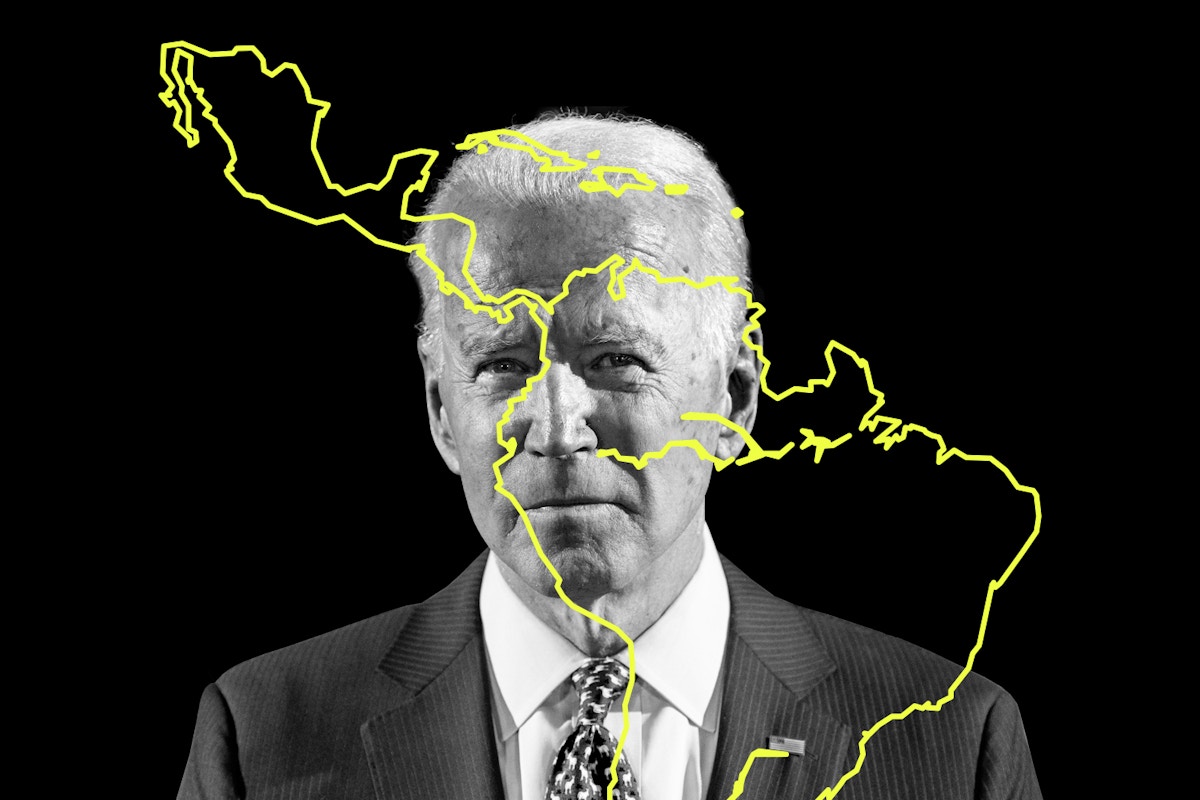

During Biden’s vice presidency, as his advisers remind us, he oversaw relations with South America; Obama, the son of a Kenyan and brought up by an Indonesian stepfather, directed his attention toward Africa, Southeast Asia and Europe. Biden will archive the Monroe Doctrine, set down the “big stick” and reach out to South American countries in search of consensual solutions to shared issues.

Biden’s priority will be to reinstate Obama’s policy of easing sanctions on Cuba. With Nicolas Maduro, he will initiate dialogue, leaving Juan Guaidó hung out to dry. In Central America, he will aim for job creation and greater economic growth in general to alleviate the streams of illegal immigration: The immigrant flow from Mexico is now at net zero; as many immigrants enter the U.S. as those who return to their country.

One of Biden’s key policies will be the fight against climate change, something that will generate friction with Jair Bolsonaro. Brazil’s president is suffering a significant change in fortune, as he previously enjoyed an intimate relationship with Trump.

Based on the above, it becomes clear that Ecuador will not be a priority. It will be a challenge for Ecuador’s incoming president to maintain the same privileged position in Biden’s government in Washington that Lenín Moreno achieved with the Trump administration. That depends on whether we choose a president who wishes to maintain relations with the major power, of course. At least one of the most likely candidates would be tempted to redo the confrontational stance that characterized the government of Rafael Correa.

*Editor’s note: The Generalized System of Preferences is a U.S. trade preference program, providing duty-free treatment to the goods of designated countries.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.