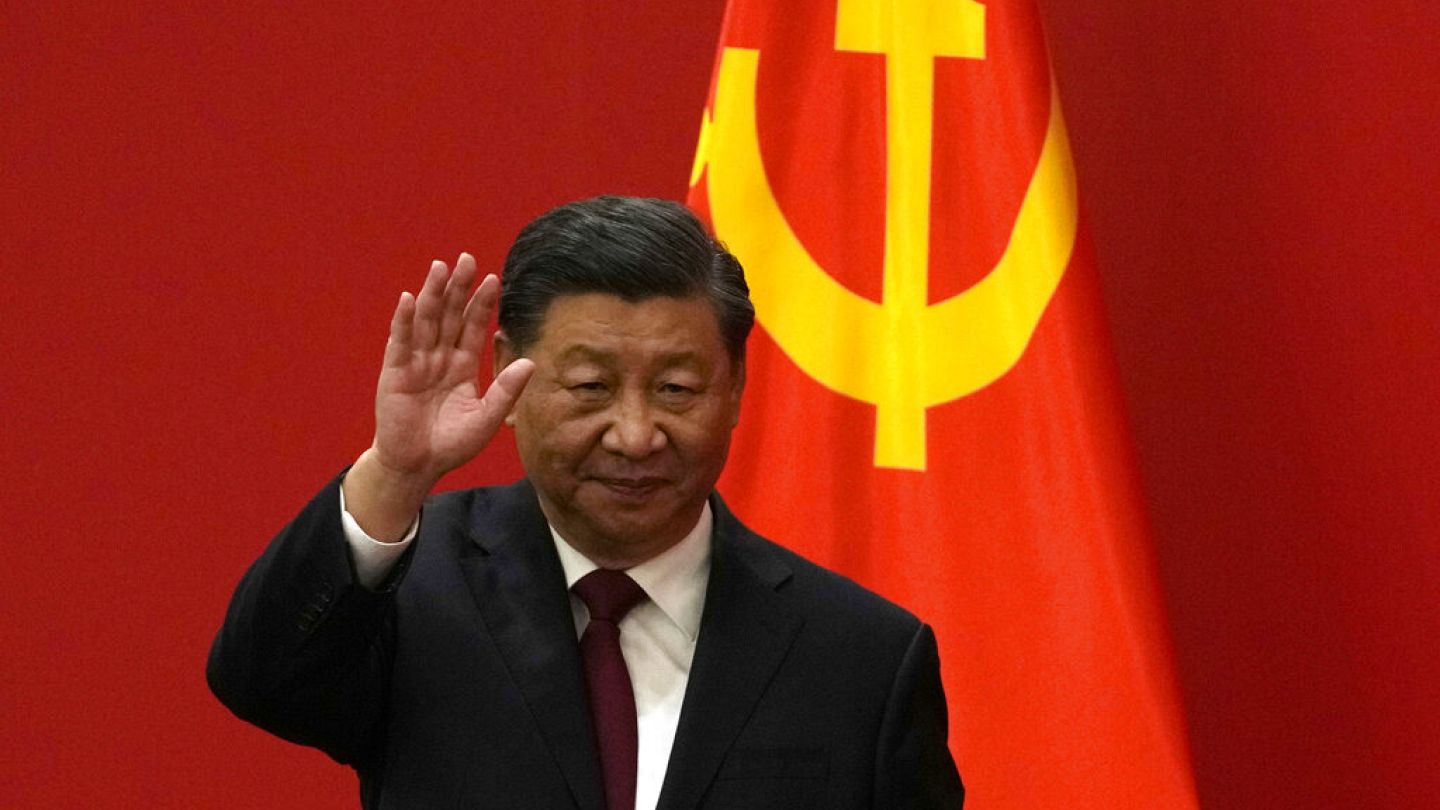

Unsurprisingly, the National People’s Congress recently and unanimously elected Xi Jinping as the president of China for the 2023-2028 term. This will be his third term, something only made possible due to a constitutional amendment introduced earlier in his tenure. At the helm since 2013, Xi is now the absolute leader. He is free to choose a supporting cast that is entirely loyal to him — assuming loyalty is something that really exists in politics, which I doubt. Throughout my life, as I have interacted with a panoply of political leaders, one thing I have learned is that where democracy fails, subordination takes its place.

As Chinese and foreign analysts point out, Xi wants to be regarded as the creator of a “China 3.0,” the dominant superpower by 2049. The 3.0 reference is an attempt to place Xi on an equal footing with Mao Zedong (“China 1.0”) and Deng Xiaoping (“China 2.0”), the two greatest political personalities of the Communist era. In reality, Xi is more reminiscent of Mao’s obsessively ideological approach than Deng’s pragmatism. The divisions he is now proposing are borrowed to a great extent from Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and reminds me as well of the Reorganizational Movement of the Proletarian Party slogans we used to see painted on walls in Portugal almost 50 years ago. Essentially they read: stay calm; be determined; strive for progress and stability; be proactive and creative; unite under the banner of the Communist Party; dare to fight; and dare to win. Behind this sloganeering lies a fear of social instability, the need to sustain economic growth to compensate for the lack of freedoms, and, above all, to safeguard the dominance by some, under the banner of the Party, over the rest of society.

The government that emerged from this National People’s Congress is little more than a complex administrative machine designed to implement the party’s directives. The submission of the administration and economy to Xi’s imperatives is a step back from the reforms begun under Deng, which had an extraordinary impact on the freedom of entrepreneurship as well as openness to foreign investment. In the case of the latter, the tendency of foreign companies to disinvest in China, and instead focus their resources on Vietnam, Thailand, India, Bangladesh, even Japan, will likely pick up speed.

On a wider scale, how might the European Union position itself politically given the prospect of a China 3.0? The answer has several dimensions.

The first of these should be to counter the current European policy of closeness and strict alignment with the United States, a policy championed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and the rest of the European Commission. Europe must avoid an unconditional alignment. It is in our interest to maintain a sufficiently distant stance with regard to the United States’ relations with China. Washington and Beijing are on a very dangerous path that could lead to an eventual confrontation. The probability of this is, let’s be clear, high. Europe needs to stay well clear of this path.

European policy must continue frequent diplomatic contacts and timely agreements, be they on a case-by-case basis or broader. This would be an approach based on prudence and evaluation of risks, step by step. Some areas would have to be closed to cooperation for strategic reasons as well as to safeguard vital needs in case of emergencies or disagreements. But this would still be an approach that prioritizes building common platforms and maintaining a productive and peaceful cooperation.

In matters of geopolitical or global interest, such as climate change, the management of polar regions, oceans, space, development aid, or the fight against terrorism, Europe must define very clearly what it expects from China as a great power and permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. This agenda would include a discussion of China’s role in the resolution of the conflict created by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, as well as, among others, forcing North Korea to adopt international behavior that respects peaceful norms. Questions regarding democracy and human rights must also be a part of this dialogue. Even if we have few illusions about what lies ahead for the people of Tibet and Xinjiang, it is fundamentally important to put these questions on the table as often as possible. Doing so does not suggest interfering in the internal affairs of China or any other country. It would simply mean that, in a new world order, including one which China 3.0 would like to help establish, we would continue to regard the security and rights of the individual as fundamental questions.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.