The Crisis Economy: On the State of Siege

The isolationist countries were few and far between: first Iraq, then Yugoslavia, and then North Korea. Their sanctions carried the U.N. stamp of approval. The American unilateral punishments were lighter and much less effective, often not extending beyond prohibiting American companies from doing business with the isolationist countries or the problematic sectors or persons in question. Today, all that has changed. Triumphalism is rampant; it is no longer an even playing field and the world is no longer flat, as Thomas Friedman opined nearly two decades ago. New American politics has decided that is so with the help of the pandemic and its complex effects. Currently, fate doesn’t care about a trade truce between China and America. The interests between China and the West have become so interconnected that an immediate cutoff scenario, or “decoupling,” is impossible. Aside from the Western supply chain that heavily leans on Chinese suppliers, most Western companies have offshored factories or partnerships in China. These things cannot just be liquidated or replaced in a few months or years. For this reason, the geopolitical tensions in the China Sea, Hong Kong, and Xinjiang might even precede the all-out economic war between American and China.

So basically, when you have lost all confidence in the system and its supposed guarantees, your country automatically starts to work under a different mindset of determining how to protect yourself and safeguard against the worst. Thus, the dynamic of accelerating and unstoppable change begins. In the South China Morning Post, former Editor-in-Chief Wang Xiangwei penned an op-ed, laying out that Chinese leadership is deliberating a new way to steer the economy called “dual cycle theory,” which will be at the heart of the next five-year plan of 2021-2025. The dual cycle is a new expression of “self-reliance theory,” which charged development in the 1950s and 1960s when China was isolated by America and later cut off its relations with the Soviet Union, leaving no alternative but to shift its gaze inward. The “dual cycle” is also based on circulating production and consumption within the country (without cutting itself off from foreign markets), so that China can liberate itself both technologically and monetarily in case it becomes separated from the Western system. China benefited from openness and a drawn-out truce with America on many levels in previous decades. Apart from economics, technology, and growth, China also took advantage of getting close to the West in order to reclaim Hong Kong and Macao. (Would that have happened if China were still under the boycott?) Beijing has maintained its claim on Taiwan, considering it a breakaway province. But this stage, too, is over, and China, according to Deng Xiaoping, must gather its points of strength and prepare for a different future.

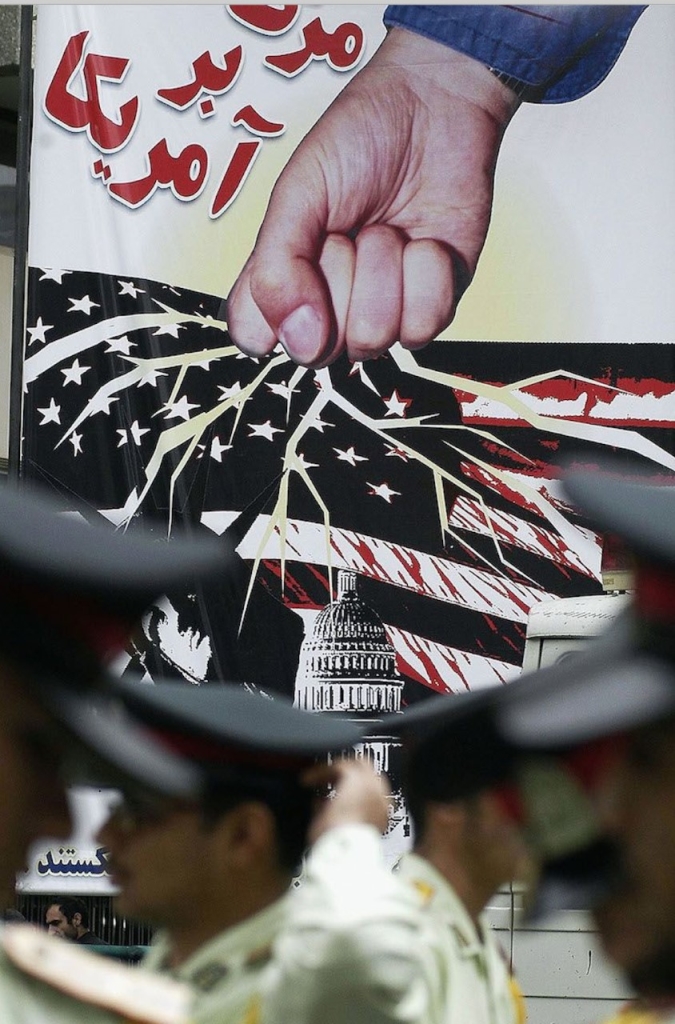

Today, Beijing, not even Moscow or Tehran, is the only capital that does not wait for American election results or count on a win for a specific candidate. To Beijing, Washington politics will not change, no matter the winner. The days of containing and clipping back China’s power according to market rules, like Barack Obama did by weaving trade alliances and in turn, besieging Beijing with pro-American Asian blocs, ended with his administration. Direct confrontation is the only remaining approach. If the two parties in America could agree on one thing today, it would surely be that confronting China is a top priority for American foreign policy. Yet, this article is not about China, although China is always in the background. In short, I present you with the tale of a country that tried to acclimate to sanctions and isolationism in years past: Iran. How did the overhaul of its relationship with the global market bring complex changes to the heart of the nation, its internal structure, and the future of its politics, with a special focus on the "welfare state" in Iran?

How Do You Gain Independence from Oil?

Between 2010 and 2020, the Iranian economy received two huge shocks (or 2 1/2). From 2012 to 2013, sanctions drove Iran to nearly total isolation. Sale of Iranian oil was almost like smuggling weapons, and foreign investment in Iran was halted immediately. In 2018, a similar shock came as Donald Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal, cutting off almost all Iranian oil exports. The majority of foreign companies stopped their projects and withdrew from the country. The Iranian economy came close to regaining its balance in 2019, until the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing global crisis put growth back in the red.

Throughout the turbulent decade between 2010 and 2020, the Iranian consumer lost on average about one-third of his purchasing power. The currency collapsed to nearly one-tenth of its value before sanctions were tightened (at the free market price). But this period hides lessons and changes that go far beyond the numbers. I can still recall, for instance, the reports in the Western press (and international organizations and centers for research) that said the Iranian state “needs” to price its oil above $90 a barrel just to break even, or its public finances would collapse. Yet dating to before sanctions, Iran never owned massive dollar reserves like Russia and Saudi Arabia and spent most of the past decade selling at half capacity, or close to none at all, sending the price of oil to rock bottom. What’s more, Iran has been severed from global financial markets and cannot borrow in case of a drought. If its dollars run out, it will immediately be unable to import what it needs. In years past, the country (until March 2020, of course) got less than $9 million from selling oil and petrol derivatives. Even in the 1980s, it would have been a paltry sum. So how has this “petrol rentier state” avoided collapse after all of these upsets? How is it that there was no famine, consumption was not driven into the ground, and public services never got cut? Even after decades of embargoes and economic warfare, while falling oil prices drove neighboring oil states into huge deficit and debt, emptying their reserves?

In a sense, the sanctions forced Iran to execute the mission that countries in the region had been talking about since the discovery of oil but did not reach, a mission that said a state "endowed by God” with oil wealth could gain independence from this resource, and the shackles of the global market and dollar system. Additionally, Iran had to free itself from the obsession with oil in the middle of an embargo and a crisis. The Iranian economist Esfandyar Batmanghelidj wrote in Bloomberg that Iran’s “non-oil” exports have exceeded the petroleum-based exports in the past year by a huge margin ($41 million compared to less than $9 million in crude oil exports). He asserts that the industrial export sector, which grew and expanded in the last few years, has saved Iran by securing the foreign market when oil revenues have become scarce. There are expectations that the value of oil exports will decrease to $5 million or $6 million this year. If America had imposed an isolationist strategy like this on Iran 20 years ago when there was a single exchange rate, industrial exports worth tens of billions of dollars, no “economy of resistance,” and it was self-sufficient in wheat and most food, it still would have been impossible for the country to cover its basic needs.

In a technical sense, two strategies were adopted. First of all, instead of betting on selling petroleum and gas directly to foreign markets (which, by the way, pads the pockets of your typical elite in developing nations with oil wealth; you produce at full capacity in exchange for “immediate” dollars that you could never get from domestic production), the sanctions forced Iran to search for an alternative path. They needed to turn imports into exports. Technically, it is easy for America and others to track crude oil shipments. The ports are few in number and well known, and outlets for sale (like specialized harbors and refineries) can be easily monitored as well. But it is more difficult to track shipments of various industrial goods, like plastic, steel and even petroleum derivatives. These can be sold in different ways, through intermediaries, or by transporting from one seller to another until its origin is unknown. Thus, sanctions remain far less effective than an oil embargo. Iran was a big importer of steel in the 1990s, but it exported close to 10 million tons of iron in the last year. Similarly, petrochemicals have become a huge source of dollars, no less than oil. (Most importantly, Iranian companies were able to design and build these factories and refineries themselves, which would have otherwise been impossible with the embargo and sanctions). Petrochemicals are a means of converting gas and petroleum for export, bringing higher value as well. Steel is partially an “energy” export (like gas) in the form of a commodity. The Iranian companies that own export factories (petrochemicals, steel, pharmaceuticals, food products, etc.) form most of the value of the Tehran Stock Exchange today.

On the other hand, there has been a focus on trade networking with neighboring countries, and direct exports to Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkey and Dubai. As Batmanghelidj says, these exports are not so large on a global scale, but they continue to hold up in the face of the worldwide crisis and sanctions. The devaluation of the Iranian currency made these goods competitive, and the exports add more than $20 million to the Iranian economy annually. Also, they are diversified exports, from fuel to food to various textiles, so their value does not suddenly rise and fall like oil.

Exceptional Measures

However, above all, the question starts with need. The developing sectors in Iran compensate for the lack of oil sales, because Iran needs close to $50 million to cover its imports (during the embargo and the COVID-19 pandemic), mostly raw and intermediate materials, industrial machines, and fodder and corn for livestock production, the basic necessities. The non-oil exports alone help cover those costs, and the export volume is not very much at all for a country the size of Iran. It makes an impact because in comparison, Iran’s imports today are extraordinarily small for a country of its size, level of consumption, and standard of living. Lebanon, which is 20 times smaller than Iran, imported a total of $20 million in 2018. So then, the exports are not the "bread and butter” here. The difference is that the country is originally producing most of its goods and consumer products domestically and does not need a huge cash flow to cover its expenses. The real difficulty lies in building a domestic production sector before you can start exporting so that you don’t appear weak and fragile to the global market.

Ali il-Qadri says that developing countries cannot possess economic sovereignty without being in control of their consumption and imports. They will only be able to realize change by adopting multiple currency exchange rates, so that one’s currency becomes “strong” domestically and “weak” to the outside. The value of one’s currency changes according to its usage (so that imported consumer goods, for example, become exorbitantly priced, while the purchase of wheat or intermediary goods for production is cheap and readily available). Such politics, which were commonplace in the mid-20th century, are considered absolute “blasphemy” today to international organizations, consultancy firms and the orthodox economic system in general. In fact, for years Iran sought to unify its exchange rate, but increasing sanctions throughout Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency forced it to reverse course and return to a multiple exchange rate system. When you read about the value of the Iranian rial today, you probably see the free market price in Tehran, which does not represent the true value of the rial against the dollar within Iran. The free market dollar value is the one one gets by importing luxury goods, or when traveling to Turkey. There is another fixed and supported exchange rate for importing necessities, medicine and food, which today is less than a fifth of the free market price. There is a third price, the “platform” price, where the government forces export companies to deposit their dollars into an exchange center. In return, Iranian companies get their foreign exchange needs taken care of. And so it forms a sort of closed market with a unique price.

In other words, there is an argument here that this policy, which the “globalization regime” has forbidden, is the only way to make one’s exports competitive without destroying the quality of life so that salaries cover basic needs without turning the country over to consumerist importing. Like China’s “self-reliance,” these measures (decreasing imports and evading the harvesting of your natural resources) have not been the thriving wisdom in years past. But if it had not taken this path, Iran would be a completely different place. Having a robust economy is not any less important than having missiles; a collapse on even one front is enough to topple others.

On top of all of that, these transformations (which happened during the COVID-19 crisis amid sanctions) have far-reaching political implications. Historically, the Iranian bourgeoisie was the private sector, the ones who took charge of world market exchange, and the traders in the import and export bazaar. They possessed the dollars in the country (like many developing nations). This societal class was interested in increasing imports and foreign exchange and investing in foreign companies operating within Iran. Doing this guaranteed that they were the agents and intermediaries when a new branch was established, a tangle of alliances between the mercantile bourgeoisie and the bureaucracy, which controlled oil revenues and the balance of import and consumption. Today, these companies (most of them owned by a mix of private equity, and public funds and institutions) represent a different kind of bourgeoisie. Its interests are linked to the state, its profits depend on access to public resources, the supply of energy and cheap gas. Also, foreign companies are not interested in taking their place or competing with Iranian companies for natural resources. Most capital accumulation will occur under this category and its related sectors (engineering companies, the service industry, etc.). They are the ones who will possess the most wealth and the investments, and thus, the political platform, in the future business sector, instead of the traditional trade route that the sanctions blew to smithereens.

Conclusion: The Fate of the Socialist State

Set aside the superficial analyses that have reigned supreme in the West about Iran for a moment, the talk of the 1979 revolution, the “pioneer state” to “religious state” theory. (In our own Lebanon, some still characterize the Khomeini phenomenon with this quote: “A bullet fired in the 7th century will settle in the heart of the 20th century.”) A young sociologist named Kevan Harris is among the growing number of academics studying the post-revolutionary social foundation of Iran. (His book is called “A Social Revolution: Politics and the Welfare State in Iran,” University of California Press 2017, and it has also been translated to Persian.) Harris classifies “revolutionary” Iran as a “developing country hostile to the system.”* Any country that tries to overcome the development challenge (like China, Brazil, Shah Iran or most of the developing nations in the 20th century), but remains defiant and hostile to important world powers will be vulnerable to war and sanctions. This forces the revolutionary country, in contrast to the Shah’s “trickle-down development” country, to mobilize the commoners to preserve order, and protect it in times of war, as we saw during the Iraq War wherein thousands of popular organizations played social, tactical, medical, economic and relief roles.

At the same time, Harris says, the revolutionary elite that ruled Iran did not produce a ruling one party, or a united organization of combined interests, but they advanced to a multipolar stage after the revolution and the Iraq War, with different wings and rivalry among the ruling elite. This rivalry was also seen in the mobilization of commoners through social organizations, gaining influence from within. Thus, many saw this as infighting and interpreted the demands and protests in Iran to be against each other. But according to Harris, this mix of opinions is what shaped the unique welfare state, also called the “martyr welfare state,” a model of social support “from below” through popular, broad and internal social networks. Compared to the Shah’s model, which was a welfare state operating “from above,” i.e., supporting certain sectors according to bureaucratic classifications (workers, army, academics, etc.) and the rest got “the royal treatment,” or whatever the ruler dished out to the poor.

This dynamic of rivalry and mobilization, Harris argues, is what defined Iran’s post-revolutionary socialist state and policies. But the challenge, the writer adds, is when these social networks in middle income countries come to a crossroads: either expand one’s welfare system to be like Western Europe (i.e., an advanced but costly system), or start rationing and confining the people, and be left with a reiteration of the Shah’s developing country, the bureaucracy that left many people out in the cold. To illustrate this further, building secondary schools in the 1980s was cheaper by far than ensuring universal education for the large post-revolutionary middle class, and starting basic clinics in the countryside was cheaper than the total cost of advanced and specialized medicine for all. These dilemmas will play out in future Iranian political rivalries, but taking on the West will remain no lesser a task than domestic politics when guiding the country. In the post COVID-19 world, in the world of the U.S.-China conflict as globalization is being interrupted as we know it, and as the gatekeeping financial system is being disrupted, the development model becomes a top priority again. The question of what to produce and who is feeding us returns, after it almost disappeared in the “open world,” ruled by the market, without citizens or sovereignty.

*Editor’s note: The quoted passage, while accurately translated, could not immediately be located in the book that is referenced and thus has not been independently verified.