To Stop Trump’s Return, American Elites Must Face the Truth: They Created Him

(Czech Republic) on 22 October 2021

by Daniel Anyz (link to original)

Many Czech journalists have protested how some media outlets such as The New York Times and CNN interpreted the results of our parliamentary elections. It was not a “retreat of populism,” as the Times supposed, and many a commentator pushed back. The winning coalitions were simply lucky that an unusually large number of votes that would have confirmed to the contrary the dominance of populist nationalism, came to nought. And in the next elections in four years, if not sooner, everything could turn out quite differently and could show the true state of things.

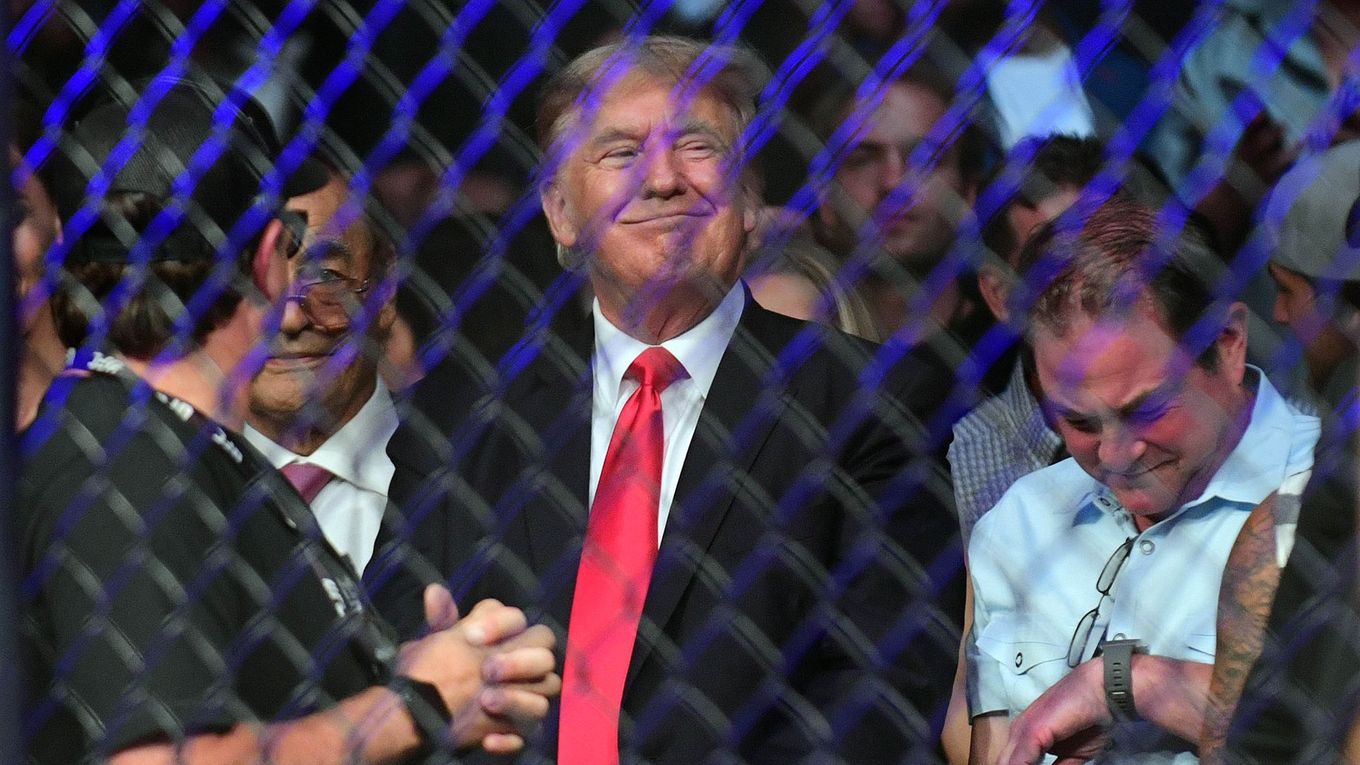

A parallel debate is taking place in the United States following last year’s defeat of the populist Donald Trump. Many are also convinced that the former president is actively preparing how to refuse recognizing the next potential loss, and to succeed at what he failed to achieve after last year’s election, when the elections results were not overturned despite a series of attempts.

For the time being, let’s leave aside this frightening scenario, which would be a genuine catastrophe for democracy in the U.S. It’s enough to simply ask what would happen if Trump were to win completely fairly in 2024 and return to the White House by the will of American voters. What would that say about America, its democracy, and its society?

Journalist and columnist David Brooks provided an indirect but nonetheless interesting answer in the September issue of The Atlantic. Brooks outlines what was and still is fertile ground for the growth of populism in the U.S., for the rejection of the current elite and their model of liberal democracy. You don’t have to agree with the author, but you have to respect him. In addition to the fact that he contemplates matters incisively and interestingly and his writing is superb, he is honest. He doesn’t hide behind the opinions of others, he doesn’t avoid responsibility. And when he’s wrong, he admits it. He doesn’t clown around, doesn’t downplay issues, he doesn’t make up excuses.

How Naive I Was

At the end of the 1990s, when Brooks was editor of The Weekly Standard, he returned to the United States after nearly five years abroad. And he discovered, with the astonishment of fresh perspective, that a new establishment had formed in America, a rising “economic and cultural elite of the information age,” as he described it at the time,* a highly educated people with “one foot in the bohemian world of creativity and another foot in the bourgeois realm of ambition and worldly success.”*

These were bourgeois bohemians, or bobos, as Brooks called them in his well-known book “Bobos in Paradise: The New Upper Class and How They Got There” published in 2000, which came out a year later in a Czech translation by Katerina and Martin Weiss.

Brooks’ depiction of the bobos was witty, in places ironic, sometimes even prickly. Nonetheless, he numbered himself among them. Even when he wrote that “when I use the word establishment, it sounds sinister and elitist,” he was convinced that the bobos would be different. “Bobos have begun to create a set of standards and mores that work in the new century. It’s good to live in a bobo world,” Brooks wrote.* At the same time, he predicted that the bobos would leave their world open, accessible from both below as well as from above.

“The educated class is in no danger of becoming a self-contained caste. Anybody with the right degree, job and cultural competencies can join,” Brooks predicted in 2000. More than 20 years later, he now, in his essay for The Atlantic, labeled that assessment as “one of the most naive sentences I have ever written.”

The Malignant Power of the Creative Class

Brooks’ essay, “How the Bobos Broke America,” doesn’t beat around the bush. Instead of openness, the exact opposite happened. “The bobos have coalesced into an insular, intermarrying Brahmin elite that dominates culture, media, education, and tech. Worse, those of us in this class have had a hard time admitting our power, much less using it responsibly,” the author notes. And he immediately enumerates three results of this arrogance.

One is education at preeminent institutions, which leads to preeminent positions. Rich parents spend more on their children’s education than poor parents, and the gap is widening. According to a 2017 study, more children from the wealthiest 1% of families in the U.S. were enrolled in nearly 40 of the best universities than those from families that make up the poorest 60% of households.

The second thing is that bobos have become concentrated in wealthy metropolitan areas where technological capital is also concentrated, to the detriment of the middle class. “[N]eighborhoods across America are dividing into large areas of concentrated disadvantage and much smaller areas of concentrated affluence.”* America is falling apart economically and educationally.

In 2016, Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton won in the 50 most educated counties of the United States by an average margin of 26 percentage points, whereas in the 50 counties with the lowest levels of education, she lost to Trump by an average margin of 30 percentage points.

In 2020, Joe Biden won only in about 500 counties, but those accounted for a total of 71% of American economic output. Trump won in 2,500 counties, which together produce the remaining 29% of the economy. Yet 30 years ago, Democratic and Republican regions were equal in terms of prosperity and income.

Revenge of the Invisibles

“If Republicans and Democrats talk as though they are living in different realities, it’s because they are,” Brooks writes. And it’s not just about economics. “The creative class has converted cultural attainment into economic privilege and vice versa.” The bobos control “the epistemic regime—the massive network of academics and analysts who determine what is true.” And more importantly, the creative class sanctifies what is worthy of attention and recognition and what, conversely, is deserving of disinterest and scorn.

“If you feel seen in society, that’s because the creative class sees you; if you feel unseen, that’s because this class does not,” Brooks points out. In 2000, when he wrote his book, he says that he underestimated “how aggressively we would move to assert our cultural dominance, the way we would seek to impose elite values through speech and thought codes.”

He underestimated, he writes further, the fact that the creative class around him erects barriers in order to protect its economic privilege. “And I underestimated our intolerance of ideological diversity.” Brooks points out that the representation of conservatives and the voices of the working class at American universities, in mainstream media and other defining cultural institutions have “shrunk to a sprinkling” in recent decades.

Brooks in no way idealizes Trump or his voters. Indeed, he considers them to a large extent the product of the disdain and arrogance of the creative class. “When you tell a large chunk of the country that their voices are not worth hearing, they are going to react badly – and they have.” People who have been declared invisible will do everything they can to be seen. People who feel humiliated want to avenge their humiliation.

Let’s Break Our Own World!

“Donald Trump didn’t win in 2016 because he had a fantastic health-care plan. He won because he made the white working class feel heard,” writes Brooks. In their revolt, Trump voters sometimes created their own reality, propagating absurd conspiracy theories, but even that is partly a result of the failure of the bobos, according to the author, “The populist right can afford to be intellectually bankrupt.” Right-wing populists don’t even have to have a political agenda. They only have to “stoke and harvest” aversion to the creative class.

As tends to be the rule with Brooks, the essay makes fascinating reading. But it ends on a rather helpless note. We know the diagnosis, but of course, what is the cure? How do we prevent Trump’s return to power in the U.S. or a possible rise of Tomio Okamura** in Czechia? In Brooks’ view, we need to change the “moral ecology” such that a degree from the elitist Stanford University “is no longer seen as signifying a higher level of being.”

But again how do we turn the whole system around?

In the final paragraph, the author addresses his own creative class and offers a challenge: “[B]lind to our own power, we have created enormous inequalities – financial inequalities and more painful inequalities of respect. The task before us is to dismantle the system that raised us.”

It is a self-critical, almost pitiless text. While it lacks a prescription for the cure, it’s still very necessary. If bobos in the U.S., or for that matter in Czechia, don’t look the truth straight in the eye, then populists, nationalists, and radicals of all stripes will only be stronger in the future.

*Editor’s note: Although accurately translated, the quoted remarks could not be independently verified.

**Editor’s note: Tomio Okamura is a Czech far-right politician, and founder of the Dawn of Democracy and Freedom and Direct Democracy parties.