‘We Hope that Common Sense Will Nevertheless Prevail in Washington’

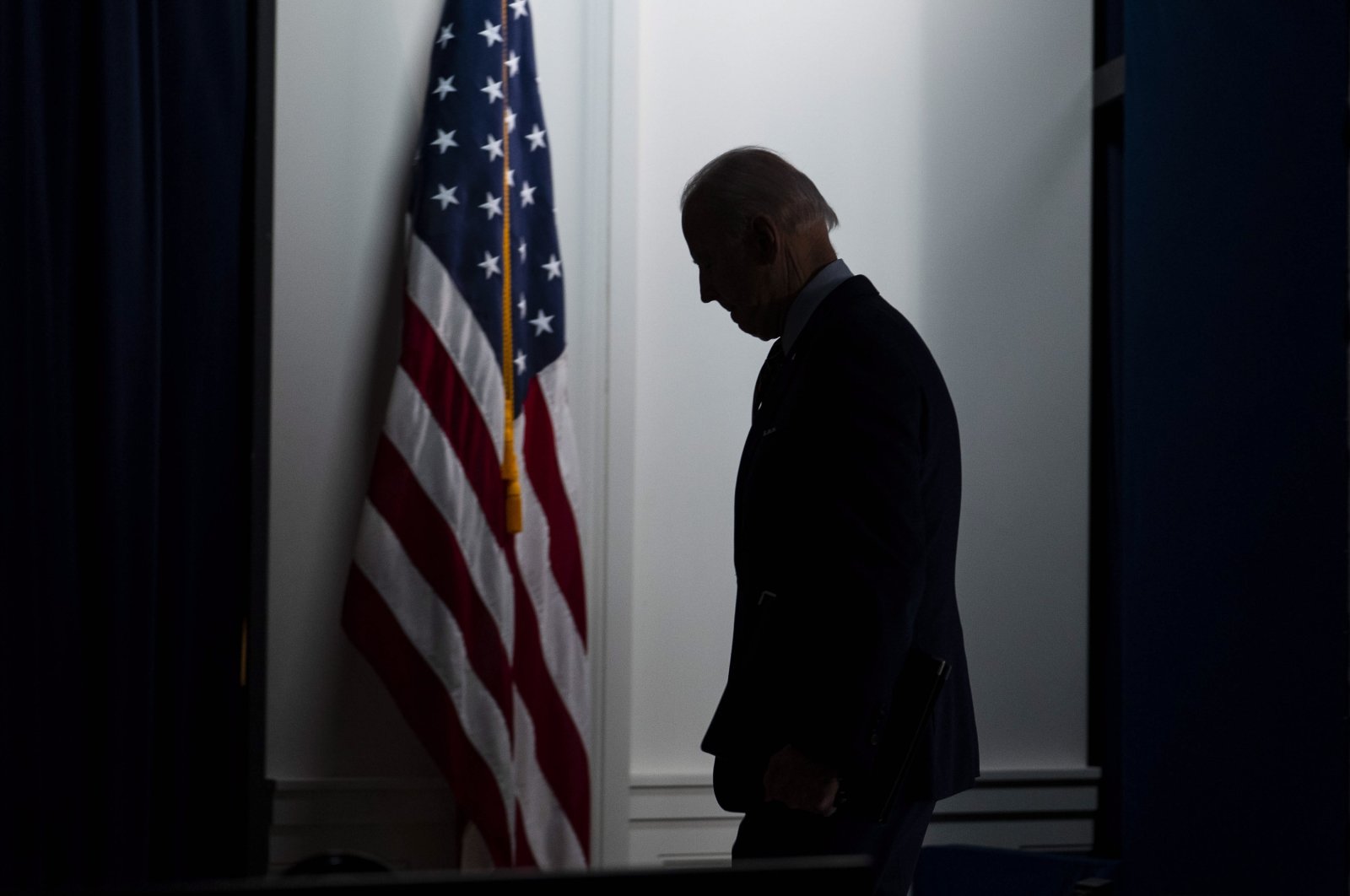

Russian-American relations are their lowest level since the end of the Cold War. The already tense situation escalated further following an interview with U.S. President Joe Biden, in which he insulted his Russian colleague, Vladimir Putin, point-blank. In a conversation with Kommersant correspondent Yelena Chernenko, Nikolai Patrushev, Secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation, described on what conditions Moscow is prepared to cooperate with Washington in the future.

Let me begin with Ukraine. In recent days, the situation in the Donbass has escalated. Does Russia have any “red lines” which, if crossed, it’s ready to openly intervene in the conflict in Ukraine?

No, we haven’t hatched such plans. But we are closely monitoring the situation. Based on its development, concrete measures will be taken.

And from your point of view, to what is the current escalation of the situation in the Donbass attributable?

I’m convinced that it’s a consequence of the serious internal problems in Ukraine, from which the government is trying to divert attention. Ukraine is solving its problems at the expense of the Donbass whereas capital has long been flowing abroad; the economy is still holding on only by onerous foreign loans, the debt on which is growing; and the remnants of an industry that were able to stay afloat Kyiv is selling off to foreigners at, as they say nowadays, democratic prices.* Even the famous Ukrainian black earth and lumber are being exported by the trainloads, depriving the country of even these assets too. And in return, it's getting merely the very same cookies that the Americans handed out on the Maidan.

About the Americans: How serious a blow to the already tense relations between Moscow and Washington was the scandalous interview with Biden, in which he answered affirmatively to a journalist’s question about whether his Russian counterpart is a “killer”?

I’d rather not draw a parallel, but exactly 75 years ago, in March 1946, in the presence of President Harry Truman, Winston Churchill delivered the famous Iron Curtain speech, in which he declared our country, his recent ally in the anti-Hitler coalition, an enemy. This marked the beginning of the Cold War.

Do you mean to say that now a new era of prolonged confrontation on the brink of war is imminent?

We’d really not like that. Today the Russian and American people have no reason to be enemies. We’re not divided as before by ideology. And the room for cooperation is vast.

The demand for us to work together has grown in light of the pandemic, against the backdrop of which the challenges and threats to global stability are intensifying. We’re seeing an escalation of politico-military tension in a number of regions, an increase in international terrorism and extremism, an exacerbation of conflicts between states, poverty, hunger, a difficult ecological situation … The list goes on and on, and each of the problems mentioned poses a direct threat to humanity.

The political situation today is indeed unfavorable; relations between the two countries are at their lowest point since the end of the Cold War. Yet the long history of relations between Russia and the U.S. shows that at decisive moments, our governments have demonstrated the ability to forge cooperation despite our disagreements.

Therefore, we nonetheless believe that common sense will prevail in Washington and a substantive Russian-American dialogue will begin on issues that, in principle, cannot be effectively resolved without a constructive interaction between our countries.

That is, there’s a readiness for dialogue on the Russian side? What issues are we talking about first and foremost?

Above all, it’s the area of strategic stability and arms control. Here there’s already a positive example. It’s our joint decision to extend the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, which, of course, was not easy for the American administration. Such an achievement gives a certain hope for establishing a normal interaction, despite the fact that the problems are, in themselves, very complex and our interests by no means always coincide.

With the administration of previous U.S. President Donald Trump, it wasn’t possible to reach an agreement on this in four years.

They tried to put pressure on us, to impose solutions that would be beneficial only to one of the parties — to the U.S. We couldn’t agree to such a thing, although we demonstrated a readiness to compromise. But that wasn’t enough: Washington wanted to dictate its terms to us. With the new administration, we managed to come to an agreement on START rather expeditiously, and on the terms that the Russian side put forward from the very beginning.

In what other areas is cooperation possible?

There’s a certain potential for joint work on such issues as the fight against international terrorism and extremism, organized crime and other challenges and threats, as well as on a number of regional topics, among them Syria, Middle East reconciliation, the Korean peninsula’s nuclear problem and the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action with Iran.

There’s demand for cooperation on acute humanitarian problems such as hunger, environmental pollution and the fight against climate change. We mustn’t forget either about the destabilizing effect of the pandemic, which can also be overcome by working together.

Discussing issues of cybersecurity is long overdue, especially considering the concerns Russia has and the accusations that have been brought forward to us for several years now.

Last year, Putin sent the White House a comprehensive proposal on cooperation in cyberspace. Has the new administration shown interest in it?

They don’t want to cooperate with us in this area, absolutely groundlessly accusing us of cyberattacks against their resources. They haven’t produced any evidence — to us or the general public — of the Russian government’s involvement in these incidents, but they make Russia out to be practically the main aggressor in cyberspace.

The American government suspects Russia and its intelligence services of being behind the hacking of the software company SolarWinds, as a result of which tens of thousands of devices in the public and private sectors in the U.S. were allegedly compromised.

This is yet another unfounded accusation against us. Our government has nothing to do with this hacking. We don’t rule out that hackers, including some living in Russia or that have Russian citizenship, may be involved in one or another instance of computer sabotage, but the state has nothing to do with it. We’ve told the Americans time and again: if you have suspicions, send us specific information and we’ll sort it out. They don’t give us anything.

Are contacts with the U.S. through the Security Council of the Russian Federation planned to continue?

They’re continuing. At the end of March, in particular, I had a phone conversation with Jake Sullivan, the U.S. National Security Advisor.

On whose initiative did the conversation take place?

On America’s initiative. By the way, it was held in a calm, businesslike atmosphere. We conversed quite thoroughly and constructively. Such contacts are taking place both through our deputies and at the expert level.

Another thing is that the dialogue should not be limited to official negotiations alone. There’s also so-called Track II diplomacy, and it has considerable potential. I have in mind contacts between the two countries’ academic communities, in the fields of culture, art and humanitarian cooperation.

These areas of partnership often undeservedly take a back seat. But in fact, it is at this level that the foundations of mutual respect and trust, a deficit of which is observed today in relations between Russia and the U.S., are laid.

Returning to the interview with Biden, I’d still really like to understand how this statement, after which the Russian ambassador to the U.S. was even recalled to Moscow, will affect bilateral relations. Can it be called unprecedented?

I’m at a loss to recall anything like it, even if we take into account the times of confrontation between the USSR and the U.S. The most fanatical opponents of our country, such as Truman or Ronald Reagan, tried to be more restrained in their public statements. Although today, when American archives are gradually opening and the personal papers of their associates are being published, we understand just what rabid Russophobia they preached behind closed doors. But they still understood that politics has its boundaries, and they should be respected. However, it can’t be ruled out that the American president was intentionally provoked to make such a statement by circles interested in increasing the tensions in bilateral relations.

But after such a thing, are meetings at the highest level even still possible at all?

We wouldn’t like for this incident to negate such prospects. Nevertheless, as I’ve already said, it’s unprecedented. We hope Washington understands the situation that has developed.

And what now? Is the Kremlin waiting for an apology?

No. As practice has shown, the Americans are, in principle, incapable of admitting their guilt under any circumstances. Even George H.W. Bush publicly announced that America would never apologize to anyone. For the American elite, it’s easier to provide a basis for any mistake with a sophisticated theory that explains why it was necessary to act exactly as they did. I would call it Hiroshima Syndrome.

After all, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Japan completely unnecessarily, even though it knew perfectly well that the Red Army was beginning combat operations against the Japanese forces in Manchuria and knew that Tokyo was ready to surrender. But for three-quarters of a century now they’ve been telling the Japanese, and indeed the whole world, over and over again that the nuclear strikes were unavoidable. They even flaunt it as a kind of punishment from above. Do you remember what Barack Obama said in his speech at the memorial event in Hiroshima? “Death fell from the sky.” But he didn’t want to say that the death fell from an American plane on the orders of the American president. We’re witnessing a rewriting of history. It’s not surprising that Japanese children already have a poor understanding of which country destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Some even think it was the USSR.

Returning to the present, what does Moscow expect of Washington? Conciliatory gestures?

Assessing the prospects for Russian-American dialogue today, it’s necessary to look at things soberly. It’s high time to recognize that for the American establishment, relations with our country aren’t determinative. Russia is seen exclusively through the prism of a domestic political struggle. And taking into consideration the unprecedentedly difficult nature of the domestic situation in the U.S. today, it’s hard to call the outlook for the further development of relations encouraging. Nevertheless, as I’ve already said, we are committed to dialogue in areas of mutual interest and hope that the U.S. will show the same interest.

The U.S. government calls Russia a “threat” to its security. Does Russia also see the U.S. as a “threat”?

Right now we see the pandemic as the main threat. For the U.S., by the way, it’s turned out to be a moment of truth. The problems that American politicians have hidden from their fellow citizens, including by diverting their attention to legends about an “aggressive Russia,” have become obvious. It’s turned out that the main threat to the lives of Americans isn’t a malevolent Moscow at all. In the U.S., the death toll from the pandemic has exceeded 560,000 people. That’s more than their losses in both world wars combined. Roughly the same number died during the bloodiest conflict in U.S. history, the Civil War of 1861-65. And it all happened, clearly, through no fault of Russia’s.

At the same time, America considers itself entitled to dictate rules to the whole world, entitled to determine the fate of mankind. Yet the question arises: Does a country that couldn’t protect the lives of more than half a million of its citizens from illness have such a right?

In Russia, the official figures of COVID-19 deaths are five times less — at 100,000 — but in fact, Rosstat reports that, on the whole, the excess mortality in comparison with the year before the pandemic reaches the very same 500,000. Doesn’t that mean that in Russia, things with COVID-19 are just as sad as in the U.S.?

We have official statistics on the COVID-19 death rate and there’s no reason not to trust them. Indeed, we weren’t prepared for the fact that everything would develop as it did and so precipitously. No one was prepared but we managed. And now we are actively helping others, unlike the U.S., which is displaying selfishness. Meanwhile, even today it’s within our power to stop the spread of the virus across the planet and save not thousands, but millions of lives — particularly thanks to the vaccines developed by Russian scientists. Our number one concern, of course, is vaccinating our population, but at the same time, we have a growing opportunity and readiness to share them with everyone interested, regardless of their political course or place on the world stage. Russia has never played political games at the expense of people’s lives and health. We have always viewed humanity as a single global community that can’t be divided according to nationality, race, or religious beliefs. Whether “Black Lives Matter” or “White Lives Matter,” let them decide that in the West. For our country, the only correct slogan is “All Lives Matter.” Our vaccines are further proof of this.

The World Health Organization mission found no traces of a man-made virus origin. Nevertheless, the theory that China intentionally provoked the pandemic is still widespread.

I suggest you pay attention to the fact that new biological laboratories under U.S. control have been springing up like weeds in the world — and by a strange coincidence, mainly on the Russian and Chinese borders. We’re assured that these are research centers where the Americans are helping local scientists develop new ways to combat dangerous diseases. However, the governments of the countries where these facilities are located have no real idea what’s happening within their walls.

Of course, we and our Chinese partners have questions. We’re told that peaceful sanitary-epidemiological stations are operating near our borders, but for some reason, they’re more reminiscent of Fort Detrick in Maryland, where the Americans have been working in the field of military biology for decades. By the way, one must take note of the fact that in the neighboring areas, outbreaks of diseases uncharacteristic of these regions are being recorded.

Are you trying to say that the Americans are developing biological weapons there?

We have compelling reasons to believe that that’s precisely the case.

And what do the Russian authorities intend to do about it?

We’ll work with our partners, first and foremost in the post-Soviet space. We’ll conclude agreements on cooperation in the field of biological security with them.

I want to remind you that the Americans don’t have their act together with chemical weapons either. At the headquarters of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in the Hague, not a day goes by that the Americans and their allies don’t come up with yet another chapter of the anti-Russian chemical dossier.

Yes, they accuse Russia of developing and using chemical weapons, including against Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia, as well as against Alexei Navalny.

But there’s zero proof and there’s no line of reasoning either, just speculation, and speculation that doesn’t stand up to even elementary scrutiny at that. One is reminded of the question from a classic: who are they to judge us?** Russia, in compliance with the OPCW, destroyed all of its stockpiles of chemical weapons, and in record time even. And what about the U.S.? Initially, it had fewer chemical weapons than Russia, by about a third, but we no longer have any, while the U.S.' are still sitting in their storage facilities. It's destroying them, of course, but without enthusiasm — the deadline was extended to 2023. The OPCW isn’t very worried about the situation; they don’t ask Washington any extra questions.

But when chemical incidents occurred in Syria, conclusions were drawn instantly, and based on information from the notorious “White Helmets.” This organization worked so “successfully” that sometimes it published its reports even before the incidents themselves. However, the date and place of the incident were changed, and the conclusions were all a carbon copy — everywhere, Bashar Assad and Russia. Now it’s known what kind of incomes, under the guise of donations, the leaders of the “White Helmets” were receiving for these provocations.

On the eve of the pandemic, Russia called on the West to temporarily waive sanctions against Syria, Venezuela and other countries in dire humanitarian situations. But the initiative didn’t meet with a widespread response. Why do you think that was?

It's all about the geopolitical strategy that the U.S. and its allies are pursuing, demolishing the whole world and defending their own hegemony as the only acceptable option for the world order. As General Charles de Gaulle once said with tongue in cheek: follow America in a column two by two, otherwise it will be bad.

Human rights, the rule of law, the free market, respecting sovereignty — Westerners shout about these values from the rooftops. But the much-vaunted Western liberalism is for the chosen. And with those countries that the U.S. and Europe don’t consider democratic, it’s a totally different conversation. Here you can do whatever you want: any sanctions on the most paltry of pretexts, the imposition of crushing loans, blackmail, confiscation of assets, brazen interference in internal affairs. I’m not even talking about the hunt for citizens of sovereign countries launched by the American justice system. Here it’s not a question of lawfulness whatsoever. These are some kind of gangster methods that have nothing to do with international law.

If an individual or many countries are unfortunate enough to cross paths with Western elites, you can be sure that no international immunity treaties or progressive laws on the inviolability of property and bank secrecy will save him. What became of Libyan assets after the assassination of Muammar Gaddafi? Where did Venezuela's reserves go after the attempt to overthrow Nicolas Maduro? In the West, it seems, it’s already become a habit to live off of the devastation of other countries. The colonial regimes, it would seem, fell long ago, but the habits remained. The Americans have probably forgotten that they were once a colony and were themselves devastated by the British.

Well, the U.S. doesn’t always take into account the interests of its Western partners either. At least that’s how it was with Trump. Biden has promised to rectify the situation and is already taking steps in that direction.

In the card game Preferans, there is the term “American aid.” The player supposedly receives some aid, but in actuality, he essentially loses. God forbid any country lives to see such help.

But it didn’t all start with Trump but with a different president — Woodrow Wilson. If you remember, at the end of World War I, he sent troops to Europe to assist Great Britain and France. How much did not only the defeated Germans but also the British and the French later pay for it? It was only when Hitler announced that he was preparing to march to the East that Germany's debts were written off.

How did Washington behave toward its allies during World War II? At the beginning of our conversation, we called to mind Churchill. Let’s cite his other statement, this time about the Americans. “We thought they’d skin us, but they took the meat from the bones too.”*** That’s what he exclaimed when the U.S. forced him to trade a dozen military bases in the colonies for 50 rusty destroyers that were already going to be cut for scrap. There’s Atlantic solidarity for you.

But that was a long time ago. At any rate, the Americans and their allies have a different model of relations now, though under Trump it was subjected to a serious test.

It’s still the same model. It’s no longer a secret to anyone that for countries, especially small ones, joining NATO is tantamount to losing part of their sovereignty. Some of our partners from Europe confidentially admit that they understand perfectly well the futility of the anti-Russian course imposed on them, but they can’t do anything about it — Washington and Brussels decide everything for them.

It’s claimed that the alliance must contain Russia. But let’s take a look at whom NATO is containing in actuality. You’d think that in a crisis, it would be possible to stop the saber-rattling and take up more pressing tasks. Nothing of the kind. This year NATO spending increased, once again appeals were made to bring spending to 2%, and as a result, the alliance’s budget is now 24 times our country’s military budget.

But that’s in absolute numbers. If you look at the actual difference in potential, it’s not so significant.

You can’t argue with absolute numbers. The question arises: who’s containing whom? Are Washington and Brussels containing Russia, or is it their mission to contain the development of Germany, France, Italy and other European states?

All in all, it’s hard to call NATO a military-political bloc anymore. Remember how in the days of feudalism vassals were obliged, at a moment’s notice from their lord, to report to him with their troops? Only today they have to buy weapons from their patron too, and regardless of their financial position, otherwise, questions about their loyalty will arise. All NATO candidates, including those who participate in programs like Partnership for Peace, should bear this in mind. All of these initiatives have a single aim: to keep sovereign players from raising their heads and pursuing pragmatic policies aimed at their own development.

Since we’re talking about Europe, I’d like to ask you about the recent visit by Josep Borrell, the head of the EU’s foreign policy service, to Moscow. Upon his return, he immediately came under a flurry of criticism: he folded in front of the Russians, they said, and failed his mission. Right after that, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov made a statement that Russia was ready to make a complete break with Europe. Is that a realistic scenario?

I support Sergey Viktorovich Chemezov’s statement. We’re not going to knock on closed doors, but we’re ready for cooperation.

Engaging with Europe is important. But being together with Europe at any price isn’t an idée fixe of Russian geopolitics. Nevertheless, we keep our doors open because we understand perfectly: there is a momentary situation that Western politicians are guided by, and at the same time there are historical bonds that have developed between Russians and Europeans for centuries. To sever them merely because the state of affairs has changed would be unwise. We’re ready to see our European partners at the same table with us solving key regional problems. We’re ready to cooperate in a wide range of areas in the economic sphere and the fields of science, culture, and technology. Today, in the midst of a pandemic, this is especially important. Right now Europe is in need of help and many European countries are asking us to share our vaccines to save the lives of their citizens. And if our help is needed, we’re ready to provide it.

In your opinion, will cooperation with the U.S. and the European Union sooner or later be normalized?

Every country defines its national priorities and lines up on the world stage as it sees fit. I don’t think dialogue for the sake of dialogue, much less for the sake of exchanging mutual rebukes, is of interest to anyone.

And yet we proceed from the premise that in the current difficult international situation, the scenario of normalizing relations would be optimal. It would accord with not just the interests of Moscow and Washington. It would be best for all of humanity. Let me emphasize once again what we started our conversation with. There’s a whole series of problems in the world today that, in principle, can’t be solved without normal cooperation among the world's leading players — Russia, the U.S., the EU, China and India.

We’re no longer in the era when having a strong army and navy was enough for global leadership. In the modern world, in the long term, the only countries that win are those that promote and implement a positive agenda aimed not at creating dividing lines but at uniting humanity’s efforts in the name of universal development and prosperity. Russia proposes such an agenda and is ready for its joint implementation.

*Translator’s note: Here Patrushev scoffs at the notion of Western democratic values with a pun: in Russian, the word for “value” and “price” are the same.

**Translator’s note: Patrushev is quoting Chatsky’s monologue from Act II, Scene V of Alexander Griobyedov’s Woe from Wit.

***Editor’s note: Although accurately translated, the quoted remark could not be independently sourced.