The Democratic victory should force the Bolsonaro government to choose between pragmatism and environmental denialism, and may spill over onto the big agribusiness exporters.

The results of the election in the United States, in which Democrat Joe Biden prevented the reelection of Republican Donald Trump, resonated in various corners of the world and one of the places that is really likely to be affected is Brazil, more specifically, the Amazon, beginning with the new president’s first days in the White House. Facing a probable turnaround in U.S. ecological policy, the government of Jair Bolsonaro sees itself at a crossroads, which leads to the largest tropical forest in the world: Should it preserve the rhetoric of environmental denialism or give in to global pressure to care for the environmental? Independent of that choice, Biden’s election puts the future of the Amazon at the center of the relationship between the two countries. “With Biden, the Amazon will go to the center of the international political debate,” projected Carlos Nobre, president of the Brazilian Panel of Climate Change.

During the campaign, Biden made a point of touching upon the issue on more than one occasion, referring to the Amazon as an “ecosystem which deserves to be protected, indispensable to the planet.”* In one of the debates with Trump, the president-elect promised to create a fund, in conjunction with other countries, of $20 billion (approximately more than 100 billion reals) for the protection of the Amazon, and warned Bolsonaro, “Stop tearing down the forest. And if you don’t, then you’re going to have significant economic consequences.” At the time, Bolsonaro reacted indirectly, labeling the declaration “disastrous and gratuitous.”

For Marcio Astrini, executive secretary of Climate Observatory, the fund, if established, is an example of the clash of thinking that separates Bolsonaro’s government from the new direction proposed by Biden around environmental foreign policy. “They would be administrations with very distinct visions of the world, above all with respect to the preservation of the environment.” the environmentalist said. “If the fund proposed by Biden really has the objective of preserving forests, it does not interest the Bolsonaro government. I find it very improbable that the Planalto** uses these values or any other money for that specific purpose.”

Astrini recalls the imbroglio over the Amazon Fund, which amounted to about 3 billion reals (approximately $56.1 billion) and was paralyzed after the minister of the environment, Ricardo Salles, dismantled the initiative’s management council. Created in 2008, the fund secured international resources, particularly from European countries, for the preservation of the forest. Since the beginning of the current government, Germany and Norway have blocked about 300,000 reals (approximately $56.1 million) owing to the weakening of the mechanisms of control and attempts by the Ministry of the Environment to reroute the money. “The resources of the Amazon Fund must be applied to combating deforestation and have oversight by civil society. But the Brazilian government doesn’t show that it is inclined to accept these terms,” Astrini said.

Forced Revision

From a global perspective, Nobre, who also is a researcher at the Institute of Advanced Studies at the University of Sao Paulo, presumes that Brazil will be forced to review its environmental policies and necessarily accept an eventual fund for the preservation of the Amazon led by the United States. “In the very short term, it could be that Bolsonaro’s government resists, but in the midterm, there will be no choice,” he explained. “The fund suggested by Biden will be the means to facilitate the entrance of American businesses into the Amazon, and is different from the model financed by Germany and Norway. Certainly with the Democratic president, the United States will join the international pressure for a supply chain without deforestation. A drastic reduction [of deforestation] will be the only alternative if Brazil doesn’t want to suffer great economic losses.”

With 17,326 fires just since October, more than double the same period a year before, the Amazon broke the annual record of the most fires in the past decade. According to the data of the PRODES project, a program of the National Institute of Space Research, which monitors the deforestation of the Brazilian legal Amazon, the area of deforestation has maintained an upward trend since the beginning of Bolsonaro’s government. Some 10,129 square kilometers (approximately 3,911 square miles) were deforested between August 2019 and July 2020, the highest index of the decade.

The expectation is that, with this year’s fires, the measurement for August 2019-July 2020 will range between 13,000 square kilometers and 15,000 square kilometers (approximately 5,019 square miles and 5,791 square miles). At the end of October, Vice President Hamilton Mourão, director of the Amazon Fund, presented a proposal to the European countries reducing the number by 6,500 square kilometers (approximately 2,509 square miles) by 2023, after Brazil fails to meet the goal of reducing deforestation by 3,925 square kilometers (approximately 1,515 square miles) this year. “The United States is among the countries which emit the most carbon gas in the world,” Mourão commented. On the eve of the American election, when questioned about the possibility of a Biden victory, Mourão said, “First, they need to resolve their own problems, so after that they can look at ours.”

Nobre’s assessment is that if the country does not want friction with the United States over the environmental question, it needs to compromise and immediately reduce deforestation of the Amazon “by at least 50%,” bringing the number to 7,000 square kilometers (approximately 2,703 square miles) closer to the verified indexes of six years before. However, the researcher points out that since 2014, owing to the economic crisis, Brazil has taken resources from the budget for the prevention of fire and deforestation, something which makes the job of imposing a new playbook by the United States even more arduous. “Eliminating the deforestation of the Amazon is difficult, but it is possible to lesson it, no doubt. This requires command and control of the region, something which, without a strong attitude from the government in this sense, is not viable.”

Experts like Nobre hope for a certain degree of moderation in language about the Amazon on the part of Bolsonaro in the coming months, in spite of the disagreement with Biden during the U.S. presidential campaign. Even if he decides to reject the billions in aid promised by the Democratic president and resists the international pressure against deforestation, the president needs to calculate the political cost of continuing to close his eyes to the destruction of the forest.

Economic Stimulus

Led by Biden, the United States also needs to encourage its multinational companies to make commitments in defense of the environment, which was never on the agenda during the Trump administration. Recently, a study from the Articulation of Indigenes people of Brazil in partnership with the American ONG Amazon Watch showed that financial institutions such as Citigroup, Black Rock and J.P. Morgan Chase invested more than $18 billion (approximately 102 billion reals), between 2017 and 2020 in businesses denounced for involvement in invasion, deforestation and violation of indigenous rights in Amazonia. “In Congress, Democrats are exerting pressure so that financiers will no longer be accomplices to the destruction of the forest. When they return to power, one hopes that they put this speech into practice,” said Christian Poirier, Amazon Watch program director.

The first manifestation of this sentiment may occur even before Biden takes office. This Thursday, one day after the election, the United States officially withdrew from the Paris climate agreement, a campaign promise kept by Trump. To mark the difference in the environmental agenda from that of his Republican predecessor, the president-elect signaled his intention to develop a plan in the U.S. with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible. The realignment of the world superpower with regard to the Paris climate agreement will be another setback for Bolsonaro, who has already thought about taking the same route as Trump and then backtracked, and is responsive to proposed international aid for the preservation of the Amazon. “Without Trump to endorse that disastrous environmental policy of President Bolsonaro, Brazil won’t know how to refuse [Biden’s fund],” Poirier said.

The Price of the Alliance

Hostage to the ideological marriage of Bolsonaro and Trump, agribusiness exportation is the sector that most fears the consequences of an imminent turn-around in geopolitics. Although the Republican president never openly advocated for deforestation nor for extraction in the Amazon, the proximity to what was conventionally called his “tropical version” helped to seal a predatory environmental agenda conducted on Brazilian soil, as Nobre points out. “Trump never publicly said he was for deforestation in the Amazon. But by sharing his denialist vision about climate change, he contributed, so that Bolsonaro felt empowered by that support to reproduce a similar discourse in Brazil.”

In May, Environmental Minister Ricardo Salles generated a revolt of environmentalists by having a publicized conversation in which he suggested taking advantage of the pandemic to shove through deregulation of environmental standards. It was just another one in a series of controversial episodes in a portfolio of episodes by Salles in his journey as minister which even included a complaint by the office of Federal Prosecutor about administrative misconduct. Nobre points out that the minister tends to lose strength when facing the state of affairs in the post-Trump world, as he is viewed as a symbol of the alliance between President Bolsonaro and the lowly clergy of agribusiness formed by lobbyists for the deforestation of the Amazon and the land grabbers.

“The Green New Deal movement is already a reality. The world economy may start to vet the importation of Brazilian products because of the deforestation of the forest. The large agribusinesses perceive this trend and are terrified. And, if there is not a significant change of orientation in the government, the pressure of the market over them will be unsustainable going forward,” Nobre said.

Performance in Check

Besides Salles, another minister who should be put in check by the Democratic leadership in the White House is Foreign Affairs Minister Ernesto Araujo. With a denialist profile, Araujo already used a cold wave in Italy to express doubt about global warming. The chancellor is viewed with distrust by the leaders of the Parliamentary Front of Agriculture in the Brazilian Congress owing to his aggressive remonstrations against China, the largest importer of meat and soy in Brazil, and against environmental protection policies. “Biden has an opportunity to articulate a great international front against populism, denialism and anti-scientism. In this scenario, Brazil will be very isolated, and that will increase the dissatisfaction of agribusiness with the president whom it helped to elect,” assesses Nobre.

During his administration, Bolsonaro has been obligated to review his positions because of the reaction of the agribusiness leadership, such as the proposition raised in the presidential transition ending the Ministry of the Environment or his own threat to leave the Paris climate agreement. “Relations between countries aren’t restricted to the area of environmental concerns, but they are increasingly determined by commercial treaties,” Astrini observed. “The Amazon never existed in the relationship between presidents Trump and Bolsonaro, but could be put on the table by Biden in future bilateral negotiations, an example of which occurred in Europe.”

Environmentalists point to the free commerce treaty forwarded recently between Mercosul and the European Union, which could be blocked by the Europeans if Brazil does not commit to reducing the deforestation of the Amazon and the emission of polluting gas. Now, the U.S. has a chance to join the European Union in the global task force to steer President Bolsonaro in a more sustainable environmental direction. “Diplomatic pressure will force Brazil to reform environmental policies so as to maintain commercial relationships not just with the United States but with Europe,” Poirier said.

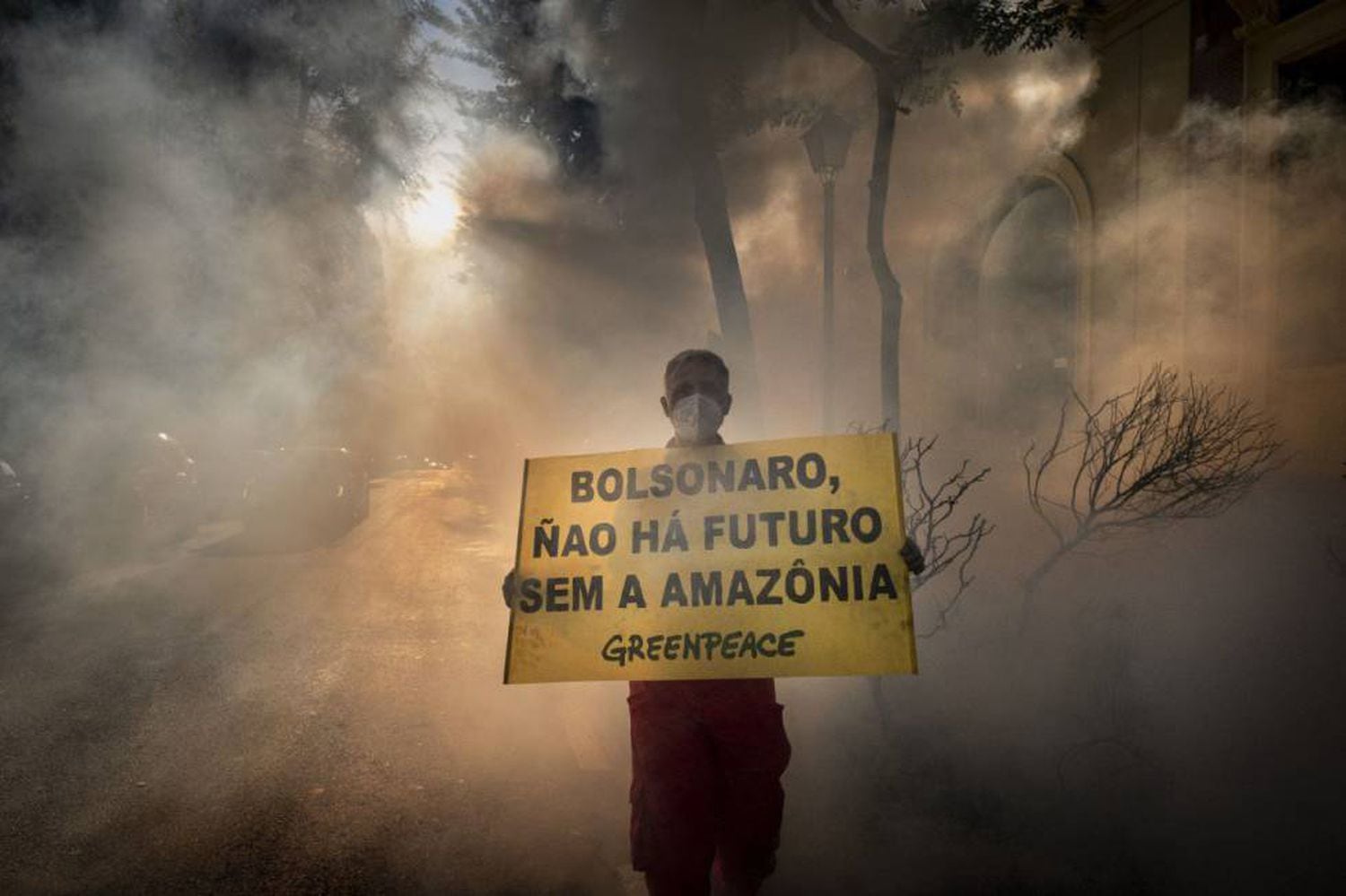

According to Datafolha research commissioned by Greenpeace, 87% of Brazilians consider it very important to preserve the Amazon and 46% assess Bolsonaro’s job of protecting the ecosystem as bad or disastrous. If he doesn’t want to suffer the same assessment from his old and greatest ally, America, the “Brazilian Trump” will need to start running the race for reelection on new environmental terms, and choose between pragmatism or denialism.

* Editor’s note: Although accurately translated, the quoted phrase could not be independently verified.

**The Palácio do Planalto in Brasília is the official workplace of the president of Brazil.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.