The 4 Downsides of AUKUS

The agreement provides that the U.S. and Britain will furnish Australia with the necessary technology and nuclear materials needed to build more than eight nuclear submarines. Additionally, the pact will facilitate joint military operations among the three countries through cooperation and technology transfer in the fields of missiles, including long-range guided missiles, artificial intelligence, quantum computing and cyber technology. As many have pointed out, this alliance is designed not only to enhance Australia’s defensive capabilities but also to curb the growth of China’s naval capacity. The acquisition of nuclear submarines will allow Australia to go beyond defending its own waters to assist U.S. carrier fleets and engage with Chinese nuclear submarines in the South China Sea, Southeast Asia and even Northeast Asia. It is also worth noting that Britain, a European nation, has promoted its interest in military involvement in the Indo-Pacific region.

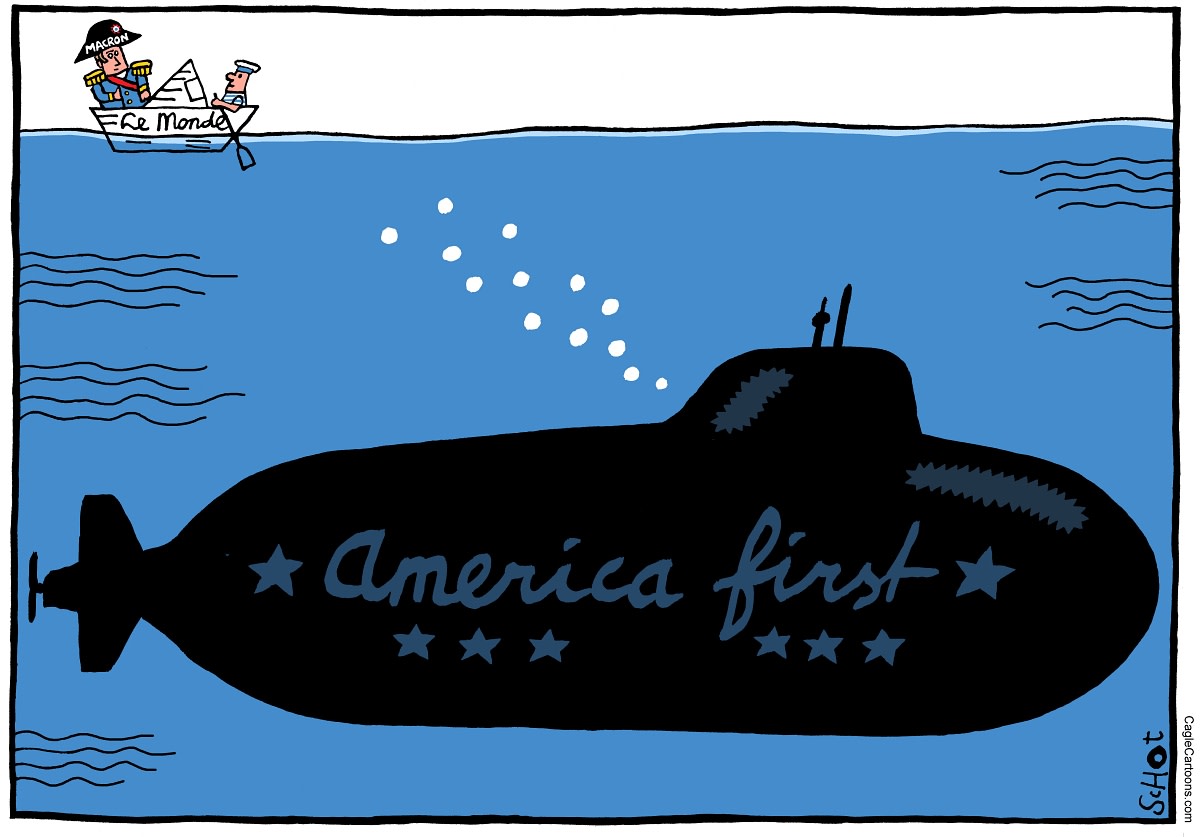

While AUKUS is clearly a great boon for U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, it also raises four serious concerns about its alliances and security in the region. First, it sheds light on the issue of certain allies being treated more favorably than others. The most prominent example is France, whose $66 billion diesel submarine deal with Australia was canceled after Australia joined AUKUS. Some mockingly characterize U.S. allies as “social classes” where Britain and Australia are the “upper class,” other Five Eyes members like Canada and New Zealand form the “middle class,” and non-Anglo-Saxon allies such as France, Germany, Japan and South Korea are the “lower class.” The discontent among U.S. allies generated by the AUKUS agreement could lead to significant weakening of U.S. alliances.

Second, AUKUS highlights the double standard the U.S. has with respect to South Korea. Since he took office, South Korean President Moon Jae-in has repeatedly asked the U.S. government for technical and material support related to the development of nuclear-powered submarines. The Trump administration rejected those requests on the grounds it could not allow the military use of nuclear power under the U.S.-South Korea nuclear cooperation agreement. However, the U.S. made an exception to this principle for Australia. The U.S. justified the decision by emphasizing Australia’s transparency regarding nuclear nonproliferation while making it clear that the U.S. would make no further such exceptions in the future. What the U.S. has done is clearly baffling to the South Korean government, a sentiment that is sure to be shared by South Koreans.

Third, from a macroscopic point of view, the alliance may increase the possibility of an arms race in the Asia-Pacific region and undermine nuclear nonproliferation. We have to first acknowledge that nuclear-powered submarines and submarines equipped with nuclear weapons mean different things, and Australia will acquire nuclear-powered submarines through the AUKUS partnership. However, this might even encourage South Korea and Japan to launch similar efforts to acquire nuclear submarines. In particular, the French government will actively promote cooperation with South Korea in the field of nuclear submarines in response to AUKUS. The South Korean government, which has already included the construction of nuclear submarines among its defense plans, will likely respond favorably. This is sure to affect Japan’s course of action as well. As China, Russia and North Korea respond in their own ways, the arms race in Northeast Asia will intensify. If this tendency becomes normalized, it will inevitably threaten the nuclear nonproliferation system in the region.

Finally, the formation of AUKUS will bring significant changes to the regional security order in several ways. AUKUS may be interpreted as the Biden administration’s basis for balancing power in response to China’s rise following the Obama administration’s Asia-Pacific rebalance and the Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy and Quad. This would most likely accelerate a new cold war with China rather than impede it. It is evident that the Biden administration, despite its advocacy of international liberalism, is planning its moves making real-time calculations.

With these concerns in mind, AUKUS seems to be an ominous signal of the onset of a new cold war through the return of geopolitics. Can we truly regard this as a good strategic move? While it may help with Washington’s short-term management of domestic politics and anti-Chinese sentiment, it is highly probable that it will produce undesirable results in the long run given the overall situation in the Asia-Pacific region. Between an alternative world order and relying on force, Washington is currently leaning toward the latter. Washington must change its way of thinking so it can better advance its interests.