President Joe Biden has recently been forced to eat crow at America’s own doorstep. As the host country of the Ninth Summit of the Americas, the U.S. insisted on handling the question of what to do about countries it labels “nondemocratic regimes” by slamming the door in the face of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua. This hegemonic behavior left other member countries of the Americas ill at ease, and many objected. Ultimately, more than one-third of the countries invited did not attend. This so-called Summit of the Americas wound up being the “U.S. Summit.”

This embarrassing situation highlighted at least two issues. The first is that by deeming Latin America as America’s backyard, the United States has long caused strong resentment among its neighbors. Latin America has gradually taken concrete action to fight back. The second issue is that America’s rallying calls have lost their luster. U.S. prestige and credibility have palpably declined. There are now Latin American countries no longer willing to comply unconditionally when the U.S. calls. Mao Zedong said, “There is absolutely no such thing as love or hatred without any reason or cause.” The reasons behind this new break with the United States are complex and deep.

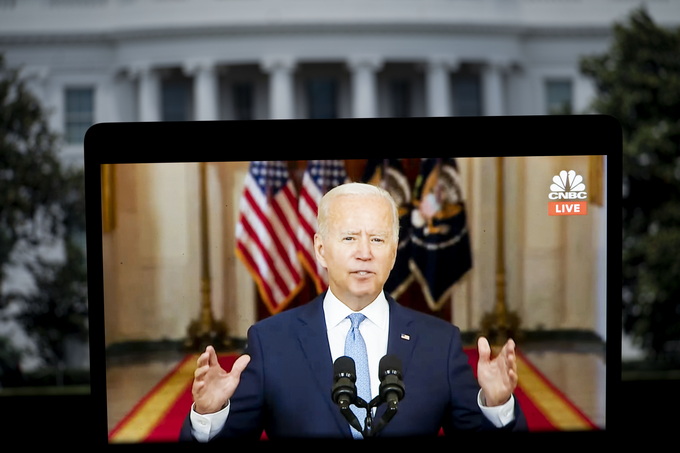

First of all, from its founding, the U.S. has never managed to slough off the pretentious airs of a vain hegemon. A favorite long-standing subject of people who observe the international community when discussing the Americas is how America regards the Western Hemisphere as its own “backyard,” and that this is the ideological standard for U.S. foreign policy in the Americas. In this era of increasingly diverse global politics, economics and society, the U.S. still retains a colonialist’s mindset, and regards all other countries across the Americas as weaklings whose only choice is to dutifully join the bandwagon, leaving the U.S. to do as it pleases without the slightest misgiving. Consider the most recent example. The reason President Biden refused to invite countries such as Cuba to the summit is both simple and crass: The U.S. does not find Cuba’s political system to its liking.

Second, the U.S. has long maintained a policy of only considering how useful the Americas are instead of seeking mutual development. For example, the American government believed that its Cold War objectives required a lengthy military occupation of the Panama Canal, U.S. energy security strategy required Venezuela to fully cooperate with American Middle East policy on oil production and now U.S economic policy requires citizens of the Americas to toil and sweat and slave in supplying the U.S with raw materials and low-end manufactured goods. Brazil must supply appetizing beef and Chile must grow appealing fruit. So, many people in Latin America who become scholars of international relations have come to hate America. Why should the Americas serve as peripheral vassals of the U.S. and accept its systematic economic exploitation?

Third, the Summit of the Americas has long lost its appeal. In 1994, President Bill Clinton established the annual arrangements for officials at the highest level of their respective governments. He hoped to launch a huge trade liberalization agreement for the whole of the Americas. However, America’s so-called trade liberalization has long been the ideological line the U.S. consistently draws in determining which countries do not support the United States enough and which kind of suppression policy is warranted. Particularly in recent years, U.S. trade protectionism has been ascendant and has burst the bubble of trust in America to keep its so-called commitments. In addition, since Biden took office, the tariffs and trade barriers of the Trump administration have continued almost entirely intact. Under such circumstances, it is difficult for the countries in the Americas to believe that the Free Trade Area of the Americas proposal has any chance of being implemented.

Fourth, the Biden administration has enough on its plate just handling domestic issues, and the countries of the Americas would rather take a wait-and-see approach. Although Biden scraped together some ideas for regional cooperation on illegal immigration, economic trade and managing the COVID-19 pandemic, countries are fully aware that America’s chaotic, polarized domestic politics have rendered such promises hollow. Given how inadequately Biden has managed inflation, there is a strong risk that he will lose control of Congress in the midterm. The countries of the Americas are naturally not going to cast a vote of confidence for Biden under these circumstances.

As the strongest political and economic power in the Americas, the U.S. should be striving to achieve regional stability and prosperity. However, the U.S. has done exactly the opposite, stirring up trouble and becoming a serious stumbling block for regional development. As the ancient philosopher Mencius said, “A just cause has many fathers, but an unjust cause is an orphan.” There is no market for the bullying ways of a U.S. foreign policy that places self-interest above everything. There is bound to be widespread resistance.

The author is an associate professor at the China University of Political Science and Law’s Institute of Globalization and Global Issues.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.