In the eyes of Joseph E. Stiglitz, winner of the 2011 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, a populist stance is not bad in and of itself, as long as it is dedicated to addressing the most relevant social problems. And he is not wrong, because populism has been a recurring political position dedicated to enumerating the most relevant shortfalls. However, the risk lies in those who have climbed aboard with respect to issues that hurt societies the most and propose measures that are unrealistic. That is, the problem is not that populism accepts that there are social burdens and identifies them. The problem is that, when the populist believes he is the modern Messiah, an anointed one, a saint who will miraculously solve the people’s problems, he ends up confusing problems with solutions.

A populist stance recognizes that current economic models have brought inequalities; however, based on factors such as ignorance and an election pitch attractive to the poor, they hang on to these problems so they can enter the political arena in exchange for gambling with the needs of society. There are problems of social order, some more marked than others, under a scheme where there are winners and losers. Yet it is not entirely the fault of globalization or free trade, because everything here is in play; from corruption, impunity, social benefit-sharing schemes and broad inequality gaps to the legacy of social policies that do not result in lifting up the poor, but merely take advantage of social anger.

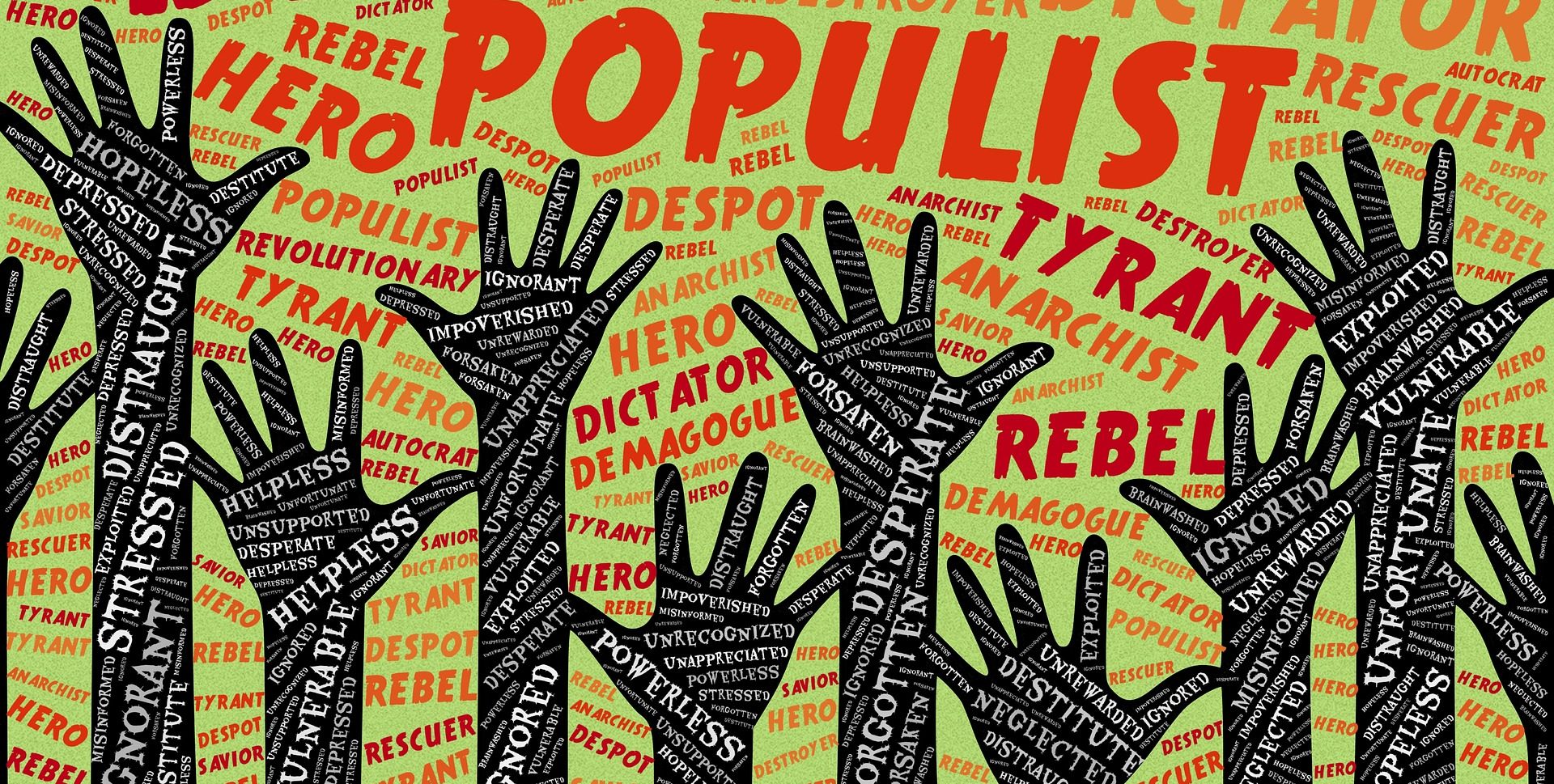

The problem is not that the populist talks about things as they are, but that he repeats empty and automatic recipes. For the populist, the poor person is the right product to use in his speech, inequality is the right element for his argument, and the closing of trade barriers the right item for his platform. He takes advantage of society’s ignorance. One of the reasons why Donald Trump won was exactly that. He took advantage of the anger that came from the crisis that arose in his country in 2008-09. Many people still suffer from the hangover of that debacle. The problem, then, is not recognizing the problems. The problem is not populism, but the populist.

Those characters who invent alternative solutions to the free market as magic formulas resemble public policy magicians, equipped with bright ideas. While the free market model has produced countless poor people, at the other extreme, we find those denying any alternatives as a third option. The fallacy lies in the fact that they cannot just save us with proposals pulled out of thin air, which may seem strong in the face of historic social shortcomings that are sustained by the hopes of the poor. What would happen if we dedicated ourselves to the necessary means to overcome social deficiencies instead of just working to put them off? The root of our poverty lies in our inability to question who benefits from remaining in a state of permanent deprivation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.