The two historical trends in 20th-century American foreign policy are interventionism and isolationism. The Trump administration restored traditional American conservatism.

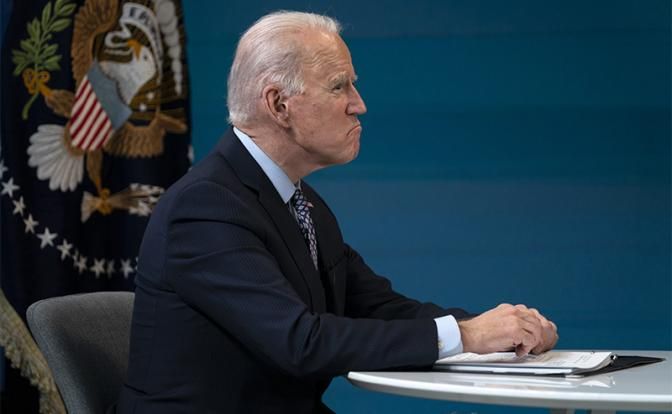

“America is back.” With this phrase at the beginning of his European tour, the 46th U.S. president, Democrat Joe Biden is expected to return U.S. foreign policy to a familiar track: revitalizing a unified West, formalized as the Group of Seven major industrial nations, and reviving the Euro-Atlantic vector. This is in contrast to the foreign policy of the previous administration of Donald Trump and the Republican Party he still dominates today, which put Euro-Atlanticism in the freezer.

Statements often heard in our country and in Europe, that in the field of foreign policy, there is no significant difference between the Democrats and Republicans, are simplistic and untrue. This was only the case during a period of ideological convergence from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the end of the Barack Obama era. Both major American parties were overwhelmed by the symbiotic relationship between the neoliberal economic doctrine of the global market and the neoconservative vision of a unipolar world under American hegemony. That’s why in foreign policy, they differed only as much as Coca-Cola differs from Pepsi — in nuanced measure.

The genesis of this symbiotic relationship can be found in 1972, when Richard Nixon, one of the most powerful American conservative leaders since World War II, won a second presidential term, following his first-term 1968 election in a defeat for Democrats by a 60 to 40 margin, and capturing 49 out of 50 states. The Coalition for a Democratic Majority, an incubator for the future symbiotic relationship between neoliberals and neoconservatives, was formed under the auspices of influential Democratic Sen. Henry M. Jackson. Among those who participated in this relationship were Paul Wolfowitz (future assistant secretary of state under Ronald Reagan, Deputy Secretary of Defense in the George W. Bush administration and then president of the World Bank), Jean Kirkpatrick (U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations under Reagan), James Woolsey (deputy secretary of defense under Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton’s CIA director), and Samuel Huntington, a future national security expert with Carter, who later made a splash with his book “The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order.” Also among this group are analysts Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz, who shaped neoconservatism in the 1980s and 1990s. They were called “Trotsky’s orphans” because they appeared in the public arena in the 1950s at the New York Intellectuals Club, where they were fascinated by Trotskyism, and then joined the Social Democrats of the United States, which still exists today as part of the Socialist Party.

The faded ideological imprint of Trotskyism is also evident in the neoconservative concept of exporting democracy, which is a distant echo of Trotsky’s export of revolutionary philosophy. Nixon’s resignation after the exaggerated Watergate affair paved the way for the ideological convergence of the two parties in the decades that followed. The Republican Reagan administration listed Democrats among its ranks in its early years, many of whom joined the Republican Party and became known as the “Reagan Democrats.” But even before this symbiosis, and after its historic demise with the pro-Trump movement, the two parties had always had substantially different geopolitical priorities.

The two historical trends in 20th-century American foreign policy are interventionism and isolationism. The Democratic Party has traditionally been the standard bearer for interventionism, based on the doctrine of Democratic President Woodrow Wilson. For the Wilsonians, America has a global mission — to form international alliances to spread democracy and capitalism.

Conversely, traditional American conservatives are more likely to follow the policies of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, who were skeptical of overly engaging in international alliances. At times, this was considered isolationist. It is no coincidence that both the Korean War and the Vietnam War were waged by presidents from the Democratic Party, which at the time played the role war party, while the Republican Party, dominated by traditional conservatives, was more of a peace party. This contrast is especially evident in the Vietnam War, which seriously escalated under Democratic presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson. Nixon, a Republican, reduced military spending on Vietnam from $25 billion a year under his predecessor Johnson to $3 billion and the reduced the number of ground troops from 550,000 to 24,000. In addition, Nixon moved to ease international relations — the SALT-1 agreement with Leonid Brezhnev’s Soviet Union was signed, and the road was opened to bilateral relations with China after the historic 70-minute Nixon-Mao Zedong meeting in Beijing, where the American leader symbolically reached out to greet Mao, years after Secretary of State John Foster Dulles refused to shake Zhou Enlai’s hand at the 1954 Geneva Conference.

And yet, in the mainstream media, and hence in the mass consciousness, Democrats Kennedy and Johnson are still hailed as doves, and Republican President Nixon is demonized as a hawk. Familiar, isn’t it? Democratic President Barack Obama received the Nobel Peace Prize, which did not prevent him from “peacefully” destroying Libya and Syria and heating up military-political tensions with Russia, while Trump was caricatured by liberal progressive propaganda as the “new Hitler,” but did not start a single war, and deescalated international tensions, paving the way for peace in the Middle East.

Wilson’s tradition of active intervention around the world was taken to the next step by the Truman Doctrine, and later neoconservatives transformed it into a doctrine of U.S. global political, economic and military domination in a unipolar geopolitical world. It is no coincidence that the famous historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. describes the neoconservatives as “Wilsonians with machine guns.”

The Trump administration restored the traditional American conservatism of Nixon to the mainstream. Today, the Republican Party of the United States is strongly dominated by a pro-Trump majority, which has relegated neoconservatives to minor roles and ended the ideological symbiosis with Democrats.

This clear ideological contrast between the Biden administration and the pro-Trump movement will long determine the shape of American foreign policy with each change of party in the White House. For Democrats, we will see enhanced cooperation in the G-7 and with the EU, active regulation of the Balkans and an escalation of gunfire, especially against Russia. For Trump’s Republicans, the Euro-Atlantic vector will head into a dead end, the interest in the Balkans will be more veiled, multilateralism will give way to bilateral relations and American power will be concentrated mainly on restraining China. And all this will take place against the background of an objective historical process that has left the unipolar world under the sign of Pax Americana.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.