U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton mentioned the diplomatic concept of “smart power” over a year ago, during which there was no improvement in the U.S. economy, but “smart power” was a big hit with her Department of State. Now, Asia can distinctly feel the “smart hand” of America.

The old dispute about the Diaoyu Islands between China and Japan recently escalated into a rarely seen crisis. The accumulation of diplomatic achievements between the two countries since the post-Koizumi era almost returned to nothing. To China’s south, China-Vietnam relations were stable for many years, but Hanoi suddenly became the center for discussing the reef dispute between Southeast Asian countries and China. Is this just a problem between China and Japan or the countries around the South China Sea? Of course not.

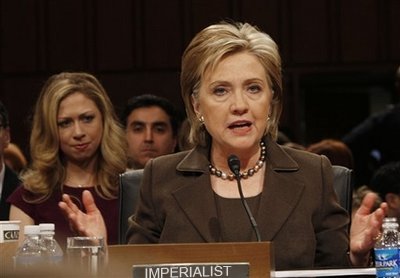

In July of this year in Hanoi, the person who publicly questioned China’s South China Sea policy was Mrs. Clinton. After the Diaoyu collision incident, it was also the United States that encouraged Japan’s resoluteness by supporting the “Japan-U.S. Security Treaty as it applies to the Diaoyu Islands.” Interestingly, in a similar Russo-Japanese island crisis soon afterwards, the U.S. declared that the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty was “not applicable” to the Southern Kuril Islands, and Japan quickly relented in front of Russia. It seems the U.S. is taking special “care” of China.

Some years after the end of the Cold War, the United States relied solely on “hard power” to run rampant around the world. It took a bite out of Saddam and pulled Yugoslavia out, but the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq has exposed the limited nature of its hard power. “Soft power,” along with the foreground of the U.S. moving toward external strategies, has popularized color revolutions. However, the global financial crisis toppled the worship of Wall Street in 2008, and the quality of soft power went downhill for the United States.

Hillary’s “smart power” diplomacy came into being when hard and soft power were not good enough. Hilary has a very complicated analysis of “smart power,” but looking at how the U.S. carries it out in Asia, it instigates and comes between the Asian countries, triggering conflicts between China and neighboring countries. [As the proverb goes], “while two dogs fight for a bone, a third dog runs away with it,” and the U.S. wants to be the energy-saving third dog.

Not only has the U.S. started using its “smart hand” in politics, but it has also appeared in the economy. In these past two years, the United States has pushed the dispute about the Chinese yuan exchange rate to its greatest extent ever. Europe and Australia are both far away from China and there are no grounds for territorial disputes, but they use dealing with the yuan as a good reason to form a clique with the U.S., and it can also distract the the world’s attention from the U.S. printing money and devaluing the dollar.

The first few shock waves of “smart power” diplomacy shook the fragile stability of the Western Pacific; it cannot be said that this was not a tragedy for Asia. The powers of Asia responded immediately because Hilary “said a few words,” which indicates that the clues to this region’s fate are still in the hands of someone else. No matter how real Asians feel their antagonism is, to some extent they are all programs written by Americans.

Asians must be clear, what is it that we want? If what we want is prosperity and peace in this region, are the so-called “checks and balances” from America’s “smart power” really a shortcut toward this goal? How much are we prepared to pay for this kind of mutual checks and balances? How confident are we in ensuring that these checks and balances will not escalate into an internal resistance by Asians in the end?

As the biggest target of “smart power,” the Chinese need to be particularly alert: Firstly to guard against the surrounding chaos caused by the United States, and secondly to guard against its “smart hand” from reaching into China’s internal affairs. There are indications that the U.S. is not only prepared to do this, but it also always finds ways to harass China’s internal affairs. Is the Nobel Peace Prize not one of them?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.