“To expect Americans, who are accustomed to thinking of their nation as number one, to acknowledge that in many areas its supremacy has been lost to an Asian nation and to learn from that nation is to ask a good deal.” No, this quote is not from a timely comment about U.S.-China relations. It’s more than 30 years old, and comes from a book titled “Japan as Number One: Lessons for America,” which was published in 1979 by a Harvard professor, Ezra Vogel. Back then, this monograph was one of the most widely read books in the United States, and set a sales record in Japan for books by foreign authors. Vogel argued that the Japanese socioeconomic model has several serious advantages over the American system: smooth and healthy industrial relations, low criminalization of society, excellent schools, and quality managerial elite with a long planning horizon.

Nowadays, those fears, for which Professor Vogel was merely the most vivid spokesman, are laughable. While 30 years ago Japan was stepping on America’s heels, only a decade later it sank into a recession that Japan has yet to overcome. Many of the Land of the Rising Sun’s national characteristics, which used to be considered its strengths, are currently acknowledged to be partly the causes of its prolonged crisis. However, the problem formulated three decades ago about the U.S. falling behind seems to be pressing once again, although no longer with respect to Japan.

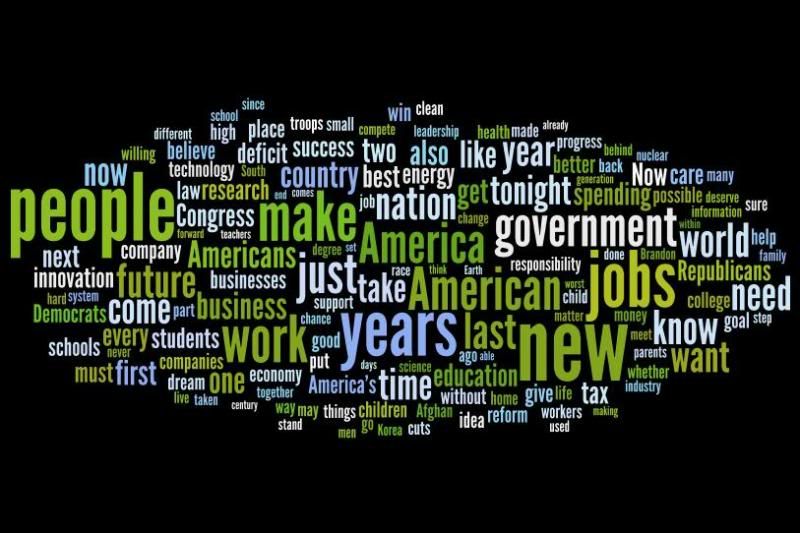

President Obama’s second State of the Union address is permeated with this idea. A year ago, Obama, in his first annual address, proclaimed the fact that American leadership is not a given. This year, he extensively developed that idea, and his speechwriters found an unexpected analogy — the Sputnik moment. The president recalled that more than half a century ago, the Soviet Union drastically surpassed the U.S. in space technology by launching the first artificial Earth satellite. American leaders were at a loss, having neither the scientific nor technological capabilities to get revenge. But the nation mobilized, and by emphasizing science and education, in 10 years the U.S. not only landed on the moon, but also made an innovative breakthrough in its economy.

Obama called the current need for research and innovation on a scale not seen since the space race a “new Sputnik moment.” This will be the aim of his administration in the coming years. The proposed model is clear and consistent. But can it be achieved in an environment without an opponent similar to the Soviet Union? In other words, without an opponent, the competition with whom, systematically underlies every policy.

The space exploration race, which was driven by considerations of national prestige, was also a byproduct of the arms race (that is, the military-political confrontation of the Cold War). Accordingly, the solution for the economic problems was found in this paradigm. In the end, America was able to overcome the problem of lagging behind Japan (that was described by writers in the late 1970s) via the military-industrial revolution, which started when Ronald Reagan came to power in 1981. He was not moved by the desire to sort out Japanese exporters, but rather the Soviet generals and members of the Politburo.

The new Sputnik moment is happening at a time when, as Obama himself has said, the United States does not have a clear enemy. Without a comparable opponent, even the arms race turned into a unilateral increase in defense spending. Ever since the end of the Cold War, America has had to compete with the entire world, proving its worth as a global leader. This requires far more resources than were necessary to contain even such a giant as the Soviet Union. However, the U.S. seems to have reached a limit in this aspiration. It’s no accident that the State of the Union announced the impending reduction in military spending, and that a recurring theme in Obama’s activities has been that sole global leadership is impossible.

Obama frequently speaks about competition: In the new world, nothing is guaranteed, even for America, while other countries are in some respects out-competing the U.S. It is noteworthy that even Russia made the list of countries that are ahead of the United States in some way, specifically, with respect to investments in railway construction.

On the one hand, it turns out that the U.S. doesn’t have to compete with anyone in the non-military sphere, because it will remain insurmountable in terms of aggregate power for at least a couple of decades. But on the other hand, the U.S. will have to compete with everyone, because everyone has something that’s more advanced than in America. In other words, this is not a race where you have to overtake another runner in the same class. Instead, you have to catch up to everyone, but they’re all running in different directions and different styles.

The rivalry during the period of the bipolar world was a competition with clear rules. Moreover, it was unnecessary to reinvent the motivating factors; the very existence of the Soviet threat was a better stimulant than any slogan. Now, such a threat does not exist. Several attempts were made over the last decade to invent one: international terrorism, “authoritarian capitalism” (China and Russia), etc. Gradually, the attention became focused on China. For instance, this fact is apparent in the sheer number of American publications about the variety of threats allegedly emanating from that country. But for now, and in the foreseeable future, Beijing doesn’t live up to the role of a systemic opponent. First of all, Beijing doesn’t want to, and second of all, it can’t.

Of course, if desired, taking advantage of some regional crisis and blowing it up to a large-scale international conflict can inflate the tension’s magnitude. But in the current chaotic conditions, the outcome would be unpredictable, and could lead to the U.S. getting bogged down in a swamp instead of a refreshing military-technical breakthrough. Iraq and Afghanistan serve as a grim reminder of this. Additionally, Obama is not a man of war, so at least while he’s in office such an attempt is not expected.

But Obama’s speech is an oratory achievement by which he hopes to inspire the society to action. The State of the Union set noble goals: education, innovation, infrastructure, national unity; and all of this in the name of the revival of the spirit of true American pioneers and the Founding Fathers. However, it’s not very clear how an increased investment in all these areas can be achieved while strengthening the social system and freezing spending (especially with an unfriendly Congress, which the President would like to unite).

In the coming years, America’s legendary ability to renew itself will be seriously tested. The test will be a perfect experiment of whether the country can reach a qualitatively new stage of development without strong external impulses and shocks. This will determine whether after a couple of decades the current fear of Chinese superiority will prove just as laughable as the prophecies made 30 years ago about Japan.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.