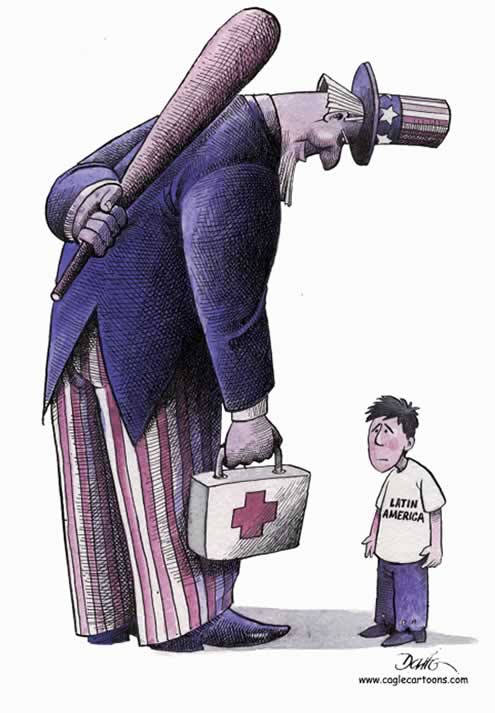

Latin America has an ambivalent relationship with its neighbor, the United States, and the Haiti situation is a prime example. America treats the island nation as if it has always been a U.S. protectorate.

Since the earthquake disaster, the USA has taken the lead in providing assistance to Haiti by sending aircraft carriers, food and water. President Obama calls it the largest aid operation in Haiti’s history. And so it should be. Haitians would starve to death without the massive help the U.S. is providing. Nonetheless, there are voices condemning that aid. In Venezuela, President Hugo Chávez complains that U.S. action amounts to an invasion and that America seeks only to extend its sphere of influence. Mexico is also critical. In fact, while American troops are welcome in Haiti, they’re not being received with open arms.

Haitians, as well as most Latin Americans, see the U.S. as trying to clean up a problem they helped cause in the first place. Ever since Haiti became the second nation on the continent to achieve independence, its larger neighbor to the north has always considered it as being within its sphere of influence – as America has always considered anything south of the Rio Grande or Key Largo. The U.S. has occupied Haiti several times in its history in order to drive out governments or install them, depending on the whim of the current Washington regime.

“We enjoy our wounds and they enjoy their inventions.”

One example is Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Aristide, elected President of Haiti, was deposed by a military coup. As mobs were howling in the streets, Bill Clinton sent U.S. troops to reinstall him into office. Ten years later, the U.S. was complicit in uninstalling him, the excuse again being mob rule in the streets of Port-au-Prince.

The problem is that the U.S. alone sets the criteria for exerting its influence. The reasons are sometimes imperialistic, sometimes patriarchal and sometimes humanitarian. But regardless of the reasons, to placate isolationist voices at home, America almost always uses the excuse that American interests have to be protected. That’s why the U.S. is looked upon with fear in Haiti, Ecuador and Mexico, even as it comes bearing gifts, providing food, digging wells or protecting the rain forests.

Suspicion is also caused by mutual ignorance of the other culture. North America operates on the basis of action: If a problem exists, it has to be solved, and the sooner the better. To the south, where nature reigns unbridled, people are more apt to be fatalistic and resigned to the inevitable. The Mexican author and Nobel Prize winner, Octavio Paz, wrote, “The world that surrounds us – exists by itself here, has a life of its own and was not invented by man as it is in the U.S. … We enjoy our wounds and they enjoy their inventions. For them, the world is a place to be improved. For us, it’s a place to be redeemed.”

Triumph, but don’t dance

America’s triumph, according to Paz, is a victory of principles over instincts. But with principles, one may triumph over everything – except the heart. The American GIs saw that in the 1960s when they occupied the Dominican Republic and halted a civil war raging there. The people called them “pariguachos” – party watchers; people who stood on the edge of a celebration but couldn’t take part in the festivities.

It’s no coincidence that Latin America developed best during those times when Washington turned its back. George W. Bush had no interest in this part of the world and directed his energies elsewhere. He sent food to Haiti but left ensuring social order to blue-helmeted Brazilian U.N. peacekeepers after Aristide’s fall. Latin America emancipated itself on the leeward side of Bush’s wars in the Middle East, condemned its dictators and stabilized its democracies.

Failure came in those places where past U.S. influence had been strongest: Nicaragua, Cuba and, of course, Haiti. The nation couldn’t liberate itself from that burden even before the earthquake. The question of whether it should be a protectorate of the U.S., of the United Nations, or of anyone else is actually obsolete. It is already one and is likely to remain so.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.