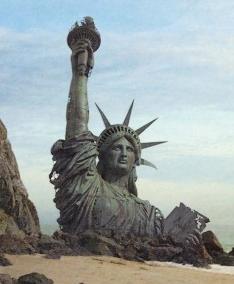

Ten years have passed since the terrorist attacks on the United States. Right after this tragedy, there was a silent consensus that the world had completely changed. Can we say that these changes are exactly what the public expected, and has the world really changed so drastically?

At first glance, the United States and the West appear to be winning. In the post-Sept. 11 decade, there has not been a single successful, large-scale terrorist attack on American soil, nor have any chemical or nuclear weapons gotten into the hands of terrorists. In other words, the United States and Europe appear to be less vulnerable than originally thought. The terrorist attacks in Madrid and London did show that no country should feel completely protected; however, there has not been a time in history when everyone could be sure of absolute safety. Another victory for the West was the eradication of the main terrorist network that was active 10 years ago, including Osama bin Laden himself. The West hence seems much stronger than it appeared right after the Sept. 11 attacks.

However, the world has indeed changed, but hardly for the better. Then-president George W. Bush declared the “war on terror” after the Sept. 11 attacks, which first manifested itself as the war in Afghanistan and, soon after that, the invasion of Iraq, with all the stories of Abu Ghraib and other dirty secrets.

The war in Iraq, it seems, is approaching its end despite all the remaining issues that could still reignite the fighting: the Kurdish issue and Iran’s increased power in the region, for example. Democratic mechanisms have brought Shiites to power in Iraq, making it the first Shiite-run Arab state. Iran, which continues to have the largest Shiite population and to be an ardent enemy of the United States and the West, is presently working on its nuclear program. The invasion of Iraq has shifted the geopolitical balance in the region, and only time can tell what the global impact of such a change will be.

The war in Afghanistan has not produced positive changes for the West. The corrupt government of Hamid Karzai virtually has no power over the country, while Taliban forces are capable of conducting terrorist attacks in places as strategic as Kabul. This war has deteriorated relations between the U.S. and Pakistan, which is becoming increasingly less democratic and more anti-Western. The current U.S. administration, however, seems to be planning to declare victory and leave the region as soon as possible. It is difficult to predict what awaits Afghanistan after the withdrawal of the troops; what remains clear is that Karzai will be forced to steer the future of his government more firmly as well as take care of his own safety.

The war on terror has disrupted interfaith dialogue around the world, especially the one between Christians and Muslims. This clash is strongly felt in Europe, where preachers of radical Islam face Christian extremists. The far-right political parties are gaining more and more support. It gets more difficult to discuss the integration of Muslims in Europe, while the prospects of Turkey becoming a full E.U. member state seem gloomier.

The hardest blow, however, was dealt to the world economy — the United States being the primary victim. Naturally, Americans were facing some issues even before Sept. 11. Nevertheless, but for the terrorist attacks, these difficulties would not by any means have grown into a global recession. The Bush administration increased war spending enormously, as two wars had to be fought. Such an increase is understandable; but why Bush kept on reducing taxes while rapidly increasing spending is difficult to comprehend. The government resorted to heavy borrowing, and now has to look for ways to balance its budget.

If bin Laden had still been alive this August, he would have enjoyed watching all the congressional debates and applauded Standard & Poor’s decision to downgrade America’s credit rating. And this is certainly not the end: President Obama and the Democrats still have to face seemingly endless discussions regarding even the tiniest budget cuts. The tea party movement seems determined to cut all government spending without considering the national interest, which is shaped also by the rest of the population. Bin Laden himself could hardly have imagined that by sending his pilots to the twin towers, he would send the United States into financial crisis and push its government to dysfunction. Not to mention such facts as high unemployment and low levels of political trust among Americans.

There is another significant outcome of the Sept. 11 attacks: The West has become evidently less democratic. Government intervention into people’s lives has intensified, with both the Internet and the streets watched vigorously. Despite the fact that such measures have prevented several terror attacks, they have, at the same time, brought the world closer to the Orwellian model of society — where citizens lose track of when the secret service watches them for well-based reasons and for reasons described as preventive measures. We can only hope that such surveillance would end along with Islamic terrorism. Yet there is nothing as permanent as impermanence. A victory against Western values would be another victory of radicalism.

All of these factors — political, economic, questions on human rights and liberty — cloud certainty in any evaluation of the post-Sept. 11 decade. The consequences of the 10-year-old terrorist attacks remain unclear, and it remains impossible to guess whether the era of terrorism has ended.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.