Edited by Anita Dixon

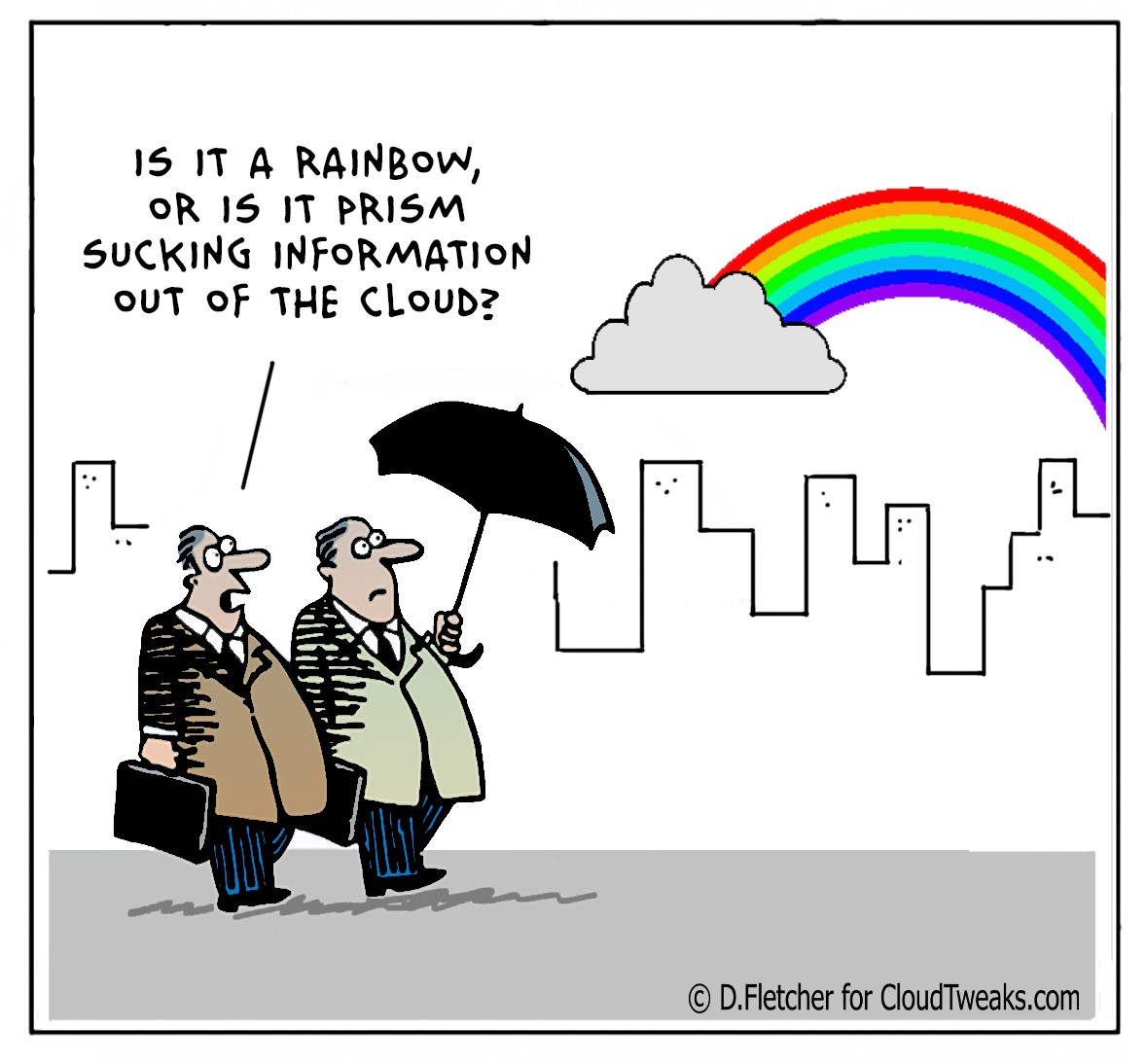

Recently, the scandal concerning the U.S. intelligence agencies’ monitoring of Internet users’ data and telephones was made public. It is known that Silicon Valley Internet giants and smartphone service providers have provided the National Security Agency with assistance in monitoring and data collecting. This program is called PRISM, and it collects information from and monitors Internet and telephone users on a large-scale. Recently, 29-year-old Edward Snowden, a former Central Intelligence Agency technician, surfaced. He is the guy who revealed some of the key information regarding the program.

What he did is obviously illegal. However, the significance of PRISM is making the American public and politicians upset. Now, the lawmakers who once passed the Patriot Act, which endows the intelligence agencies with a broad range of information gathering powers, must have realized, uneasily, that the extent to which the intelligence agencies are collecting data and prying into people’s privacy is on the verge of being out of control.

Perhaps this is only the tip of the iceberg. In other words, who can protect the privacy of the government, Congress and the judicial branch from being monitored by the intelligence agencies as well?

Needless to say, the public must be more upset: their daily life in its entirety might have been monitored and censored. They find that the law is a mere scrap of paper to the intelligence agencies. Not a single means of communication is safe, ranging from letters to telephone, smartphones and the Internet. What’s more, they realize that after the scandal, the government and the NSA not only admitted that it had indeed happened, but also that they were concerned about the fact that the leakage of the program would pose a serious threat to national security, instead of the public’s privacy.

Obama called the criticism against PRISM speculation and refused to apologize for the eavesdropping. Rather, he considered data intercepting to be “worthwhile” and demanded the public understand that 100 percent security and 100 percent personal privacy are not to be achieved at the same time, and that everyone has to give up what he has to.

What he said is rather easy yet also hard to understand: how much weight should be granted to security and how much to privacy? To what “degree” can we define the boundary and by whom? How can we ensure that the government and intelligence agencies do not cross the line if they refuse to be transparent?

American politicians, especially the ones in power, are most influenced by political interests. It is not hard to see that if the electorate is beyond upset about the protection of its privacy, more politicians will feel that their concerns are closely related to those of the public and start to hurl questions at PRISM as midterm elections are approaching fast.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.