Putin's Gamble in Ukraine and Why It Could Go Wrong

(Spain) on 23 March 2014

by Jordi Pérez Colomé (link to original)

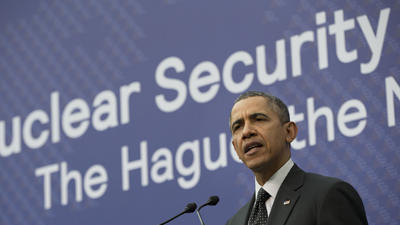

At the press conference given to explain the move, Obama said that Putin at times appeared to have "that kind of slouch, looking like the bored kid at the back of the classroom." He was referring to this photograph taken in Northern Ireland in June: [photo]

He also said, "When we have conversations, they're candid, they're blunt, oftentimes they're constructive."

Susan Rice, Obama’s national security advisor, gave a press conference on March 21, 2014. When she was asked whether the crisis in Ukraine was "prompting a fundamental reassessment of U.S.-Russian relations," her reply was, "Yes." The transcript notes "laughter" at this point, which is also audible in the video recording (from minute 16), but the reason for it is unclear. The New York Times, also present, did not record the laughter. It must have been down to nerves.

Since the end of the Cold War, relations with Russia have been nothing to write home about. Each president has made an effort to improve matters, but by the end of each mandate, relations have tended to be worse. George W. Bush started the ball rolling with the meeting, after which he famously said that he had looked President Putin in the eye and "was able to get a sense of his soul."

Three dozen meetings later, Putin and Bush met for the last time right after a NATO summit to discuss the entry of Ukraine and Georgia into the organization. NATO decided in the affirmative, though no specific plan was agreed on. A few months later, Russia invaded Georgia. Two independent Georgian provinces, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, were the product of the conflict.

Dmitri Medvedev was president by the time Obama came to power, and an attempt was made at a "reset." Hillary Clinton and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov even pressed a button. The consequences have been so dubious that the photograph of the button-pressing will surely be used by Republicans against Hillary, should she run for president in 2016.

And the fallout, naturally, has been no better for Obama. Now, with the Russian annexation of Crimea, the situation appears to have deteriorated. And if Russia decided to invade other Ukraine provinces in the east of the country, the crisis would become even more acute because the Ukrainian Army would be sure to respond. It would be an extraordinary move if Putin dared to make it. In order to better understand his motives, it helps to consider why he might have invaded Crimea. I have come up with three plausible reasons:

- He needs a war. This is the domestic policy argument. Putin is no longer the president he was a decade ago, set to recover Russian pride and lead a now buoyant country. His popularity was maybe in need of a boost, and he has achieved that boost in Crimea. It also gives him an excuse to control dissidence at home. Here is how he described it in his announcement of the annexation of Crimea:

Some western politicians are now threatening us, not only with sanctions, but with the prospect of more serious problems here at home. I would like to know what they have in mind: action by a fifth column, this disparate band of "national traitors," or are they hoping to deteriorate our social and economic position in order to provoke social unrest?

If more protests take place in Russia in the near future, Putin now has his excuse to suppress them: The west is inciting unrest in order to oust him from power. Backed by this reasoning, he could defend himself against the "traitors" with every means at his disposal.

- No to NATO. Shortly after the fall of the Iron Curtain, in February 1990, President George H. W. Bush promised Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would not advance toward the east. It took fewer than 15 years for it to reach the Russian frontier with the entry of the three Baltic nations, among others, into NATO.

The great American diplomats Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski considered it a mistake, and it is logical that Russia should react. It is realism in its purest form, according to American foreign relations theory. The presumed hope is that Russia might become a special ally in any future squabbles with the real great rival, China. (George W. Bush warned future U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, prior to his first meeting with Putin, "One of these days we will have to take care of the Chinese,"* meaning that good relations with the Russians would be an advantage.)

Putin, naturally, agrees:

They have lied to us many times, they have made decisions behind our backs, they have presented us with fait accompli. That is how it was with the eastward expansion of NATO, that is how it was with the deployment of military infrastructure on our borders. They go on saying the same thing, "There is no cause for concern." It is easy to say.

It is said that Putin is acting this way because he smells weakness in Obama. The argument is similar to the one used about Georgia in 2008. In a cable to WikiLeaks, the ambassador to NATO then described it in the following terms:

The allies controlled by Germany deny that the decision taken in Bucharest on the future admittance [to NATO of Georgia and Ukraine] provoked the Russian aggression, while the majority of the other nations (new members from the expired Warsaw Pact, and Canada) see it as we do: that Russia misinterpreted the rejection of Membership Action Plan [a firm plan to begin to negotiate the entry of Georgia and Ukraine, which in reality was only a "promise" to consider their entry] as a green light to invade Georgia.

- He wants Eurasia. Putin aspires to unite countries within the former Soviet orbit in a collective similar to the European Union called Eurasia. He needs Ukraine, with its potential for many millions of consumers in a possible free trade agreement. The crisis in Kiev in November began with President Yanukovich’s request to postpone the signing of agreements with Brussels. Moscow rewarded him with a fat check. The Ukrainians rejected Yanukovich’s decision and took to the streets to demonstrate. Putin was unhappy with the result of the revolt and responded with Crimea. And that brings us up to date.

Putin's maneuvering may be working well today, but it is unlikely to continue to do so. One of his great allies, Lukashenko’s Belorussia, seems to be distancing itself from Moscow. Signing an agreement more or less freely is not the same as doing it under duress. The new president of Ukraine has already signed a preliminary agreement with the EU similar to the one Yanukovich evaded. The agreement will be finalized by the new president to emerge from the May elections — provided he chooses to do so.

Putin’s decision-making on Ukraine may have in fact been an improvisation based on the three factors above. The problem is that, beyond Crimea, Putin's strategy does not look set to be a winner in the long term. His actions will oblige those who purchase gas and oil — Europe, above all — to play safe by shopping further afield; and the U.S. has had more reserves than any other country for a few years now. International investors are also likely to see Russia as a less reliable proposition, undermined by the pressure that sanctions will inevitably bring to bear. Even Moscow's Eurasian allies will be more wary now.

In the heat of the moment, Putin has won. Now comes the hard part. The world, however, should be duly concerned at the prospect of Putin electing to continue with heated conflict as his best option.