Like disco culture, nightclubs and bars in the United States have been safe havens for minorities such as homosexuals, blacks and Latinos for the last 50 years…

Among the many heated reactions that appeared on social media on Sunday regarding the Orlando massacre, a post by the California record label Dark Entries warmed the hearts of many dance music lovers who were particularly affected by this hateful crime: an old photo booth snapshot of the electronic disco producer Patrick Cowley full-mouth kissing the singer Jorge Socarras, who was his lover and collaborator in the musician duo “Catholic” during the latter half of the 1970s.

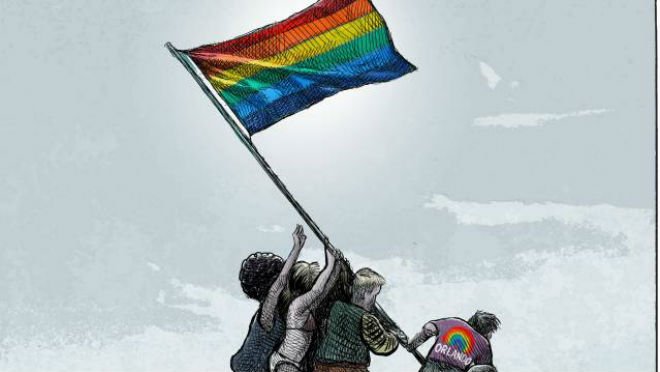

Counterculture

This post followed the call by the writer K.M. Soehnlein to “flood the world with pics: #twomenkissing” in response to the claims by Omar Mateen’s father that he had become angry after seeing two men kissing in the street. But this post also allows us to identify the section of the American population that was targeted and the very specific context in which the killing was carried out: a gay club predominantly frequented by American Latinos, i.e., a group which was doubly a minority. And this in a country that considers itself to be the sum of communities with their own profiles and characters, rather than one lone community which cements the principles of republican universalism, like in France.

Beyond the claims of the Islamic State and Mateen’s mental instability, the image reminds us about the extent to which the club in its diverse forms (ballroom, bar, giant nightclub) constitutes a place of refuge and solidarity for the battles which have been fundamental for American minorities over the past five decades. Several works on this subject have appeared over the last few years, such as Tim Lawrence’s “Love Saves the Day” or “Turn the Beat Around” by Peter Shapiro (published in France by Allia in 2008), recounting the emergence of this counterculture and the little-known social history behind the so-called hedonism of disco and the musical movements that followed it (hi-NRG, house and garage) or the flamboyant clichés of beautiful people in New York’s Studio 54.

Reinvented

The first private establishment recognized in the history of American disco clubs, Loft, opened by David Mancuso in his home in Greenwich Village in 1970, was envisaged as an escape from traditional discos where homosexuals were subject to harassment from clients as well as from security guards and police. Thanks to their membership systems, Loft, then Nicky Siano’s Gallery and the utopian Paradise Garage founded by Michael Brody in 1977, became havens and places for sexual, cultural and social experimentation for the most precarious and vulnerable populations in the American homosexual community, particularly those of African-American and Latino origin.

The emergence of subgenres of dance music which followed the explosion of disco in popular culture from 1974 onward is almost systematically linked to the places of emancipation which were emblematic of their city or neighborhood: EndUp in San Francisco where Hi-NRG was invented, Warehouse, Music Box and Powerplant in Chicago where house music was born, Zanzibar Club in Newark, New Jersey, where the seeds of garage were planted. On their dance floors or in their backrooms, the dancers and the DJs gave birth to uncensored music, and gay culture communed together, enjoyed themselves and freed themselves. In this shelter from the world, music and culture was invented and reinvented nonstop, which continues to happen today. Far from the large electronic dance music gatherings which regularly bring together thousands of young, heterosexual WASPs, one of the most vigorous and angry scenes in current electronic music is emerging from the Texan music producer Lotic, a young gay African-American, who is as engaged in the recognition of his adventurous, unbridled music as he is of his identity: that of plural, queer and transsexual.

Because they are by definition places of abandon and pleasure, we have forgotten to look upon these clubs as outposts of action and of unconventional society for a long time. The massacre in Pulse has just reminded us that they have never stopped being this, with reckless abandon.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.