The Euromissiles Crisis and the Fear of Nuclear Escalation

(Italy) on 21 October 2018

by Franco Venturini (link to original)

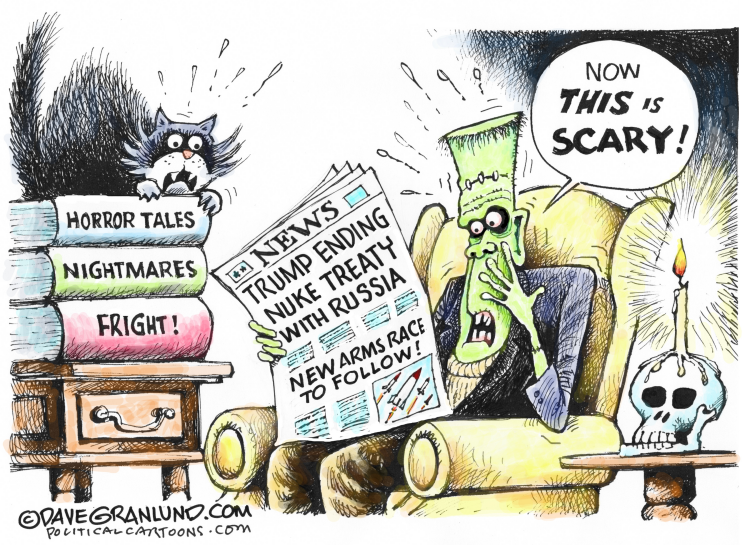

The treaty that U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev signed in 1987 to remove all ground-based missiles with a range of 500 to 5,500 km (310-3,240 miles) was, as everyone knew, subject to fierce debate between Moscow and Washington. U.S. President Barack Obama had already accused Russia of breaching the terms but would not have dreamed – because of strong opposition from his European allies for one thing − of condemning the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty. Trump is however very different and has, for the most part, a negative relationship with Europe. Without a second thought, the president has made clear his decision to tear up the agreement. Unless John Bolton can convince Russian President Vladimir Putin otherwise (seemingly an unlikely prospect), Trump has opened the door to a new European cold war.

With the exception of London, which has been at loggerheads with the Kremlin for some time, European capitals have already started to protest. However, if taking a stand at this time is essential, an understanding of what is going on is even more crucial. On the Russian side, assuming that the 9M729 missile system based at Kasputin Yar does constitute a violation of the INF (and European military services doubt this), its strategy would be a well-known and longstanding one. That is, create fear among Europeans and isolate them from the Americans, which would lead to a kind of socio-electoral “Finlandization” and ultimately a nuclear decoupling, leaving Europe essentially defenseless. That was the strategy behind the deployment of Soviet SS-20 missiles in the ‘80s, which the West countered with the deployment of Pershing II and cruise missiles until the INF agreement was reached. This sequence of events is a memory from the Cold War, something we should all have moved on from in these times of cyber-attacks and “hybrid warfare.”

However, if we shift our gaze to possible American motives, it becomes clear that a cold war in Europe is still very much of contemporary concern. It is widely known that Trump is not Europe’s biggest fan. He has clashed repeatedly on issues such as the environment, trade, Iran, supplying lethal weaponry to Ukraine, financing NATO and the politics of imposing sanctions. In this context, two strategic alternatives for his “America First” policy exist: either break the community framework (nationalists and populists are attempting to do this with former chief of staff Steve Bannon’s collaboration) or use the issue of security, an area which Europeans have neglected for many years, to force individual allies to toe the line. If Russia were behind a return of the Euromissiles, it would suit America’s purpose perfectly, even if it would be desirable for Washington to have some form of proof that Moscow was violating the INF.

Wherever the truth lies, and whether Russian responsibility or American interests are at play or not, continental Europeans now risk facing a new state of affairs. It is perhaps a situation that our eastern members will be happy about. They have been condemning the strategic misconduct of the Kremlin for some time (Hungary aside; Poland is even ready to finance a permanent American base on its territory). However, 30 years on, would other countries – and Italy in particular – be willing to accommodate more Euromissiles pointed at Russia, and, in so doing, become a target themselves? How would public opinion, currently dominated by other concerns, react if a nuclear cold war, one accepted or even desired by the world’s two great atomic superpowers, were to be fought in Europe again, just like in the ‘80s?

Bolton’s trip, Putin’s response and question marks over Trump’s credibility (he has contradicted himself more than once, especially when it comes to relations with Russia) are all stark reminders of the absence of Europe from a strategic confrontation in which it will be exposed to the greatest risks. They also herald the dawn of a different and more dangerous world from that of 1987. China is now a third protagonist and a consideration in the United State’s desire to cast aside the limitations of the INF; military lobbying for new technologies is weighing on the political classes (in Washington as much as Moscow); and the nuclear threat, just when it seemed to have passed, is ready to make its great return. Above all, there is also the prospect that the Americans and the Russians, besides quitting the INF, also decide against extending the New START treaty on intercontinental missiles, which is due to expire in 2021. It is to be hoped that Italy’s prime minister Giuseppe Conte, who is due to meet Putin on Wednesday, takes all of this very strongly into consideration, meaning that Italy should also make its case to Trump. It should do this, if possible, before Trump and Putin meet on Nov. 11 in France to commemorate World War I, and pretend nothing is going on.