Trump has more reasons than Nixon to legally oppose surrendering all White House transcripts, should he decide to go down that road. But the risk is there and will last until the 2020 election.

The transcript of a July phone call between Donald Trump and Volodymyr Zelenskiy has already led to an impeachment inquiry by the House of Representatives against the president of the United States.

The transcripts of the president’s phone call are not, as one might think, real transcripts, in the sense that they were made from recordings of these calls and, thus, are subject to verification.

Memcons, which is the name given to this type of transcript at the White House, come from the notes taken by officials present during the phone call or in the next room, with direct access to what is going on. Phone calls and other conversations, such as meetings or conferences involving the U.S. president, are not currently recorded.

There are thus two levels of discussion about the content of the phone call that is the basis for the ongoing impeachment inquiry: First, regarding the accuracy or veracity, in whole or in part, of the transcript itself, the memcon, written and reviewed by officials; Second, the text of the transcript itself.

If the conclusion is that the memcon does not faithfully reproduce the telephone conversation between the two presidents, or at least with a reasonable proximity to reality, investigators cannot move on to the second analysis, I believe.

However, in the House of Representatives, there is already talk about evaluating other memcoms of Trump’s telephone conversations or meetings with other presidents or politicians on topics relevant to U.S. national security, given the perplexity and discomfort generated by the conversation with the president of Ukraine.

If the intention to evaluate additional memcoms is acted upon, the White House could be obligated to surrender other memcons to investigators appointed by the House of Representatives for the impeachment inquiry, whether they are classified or not.

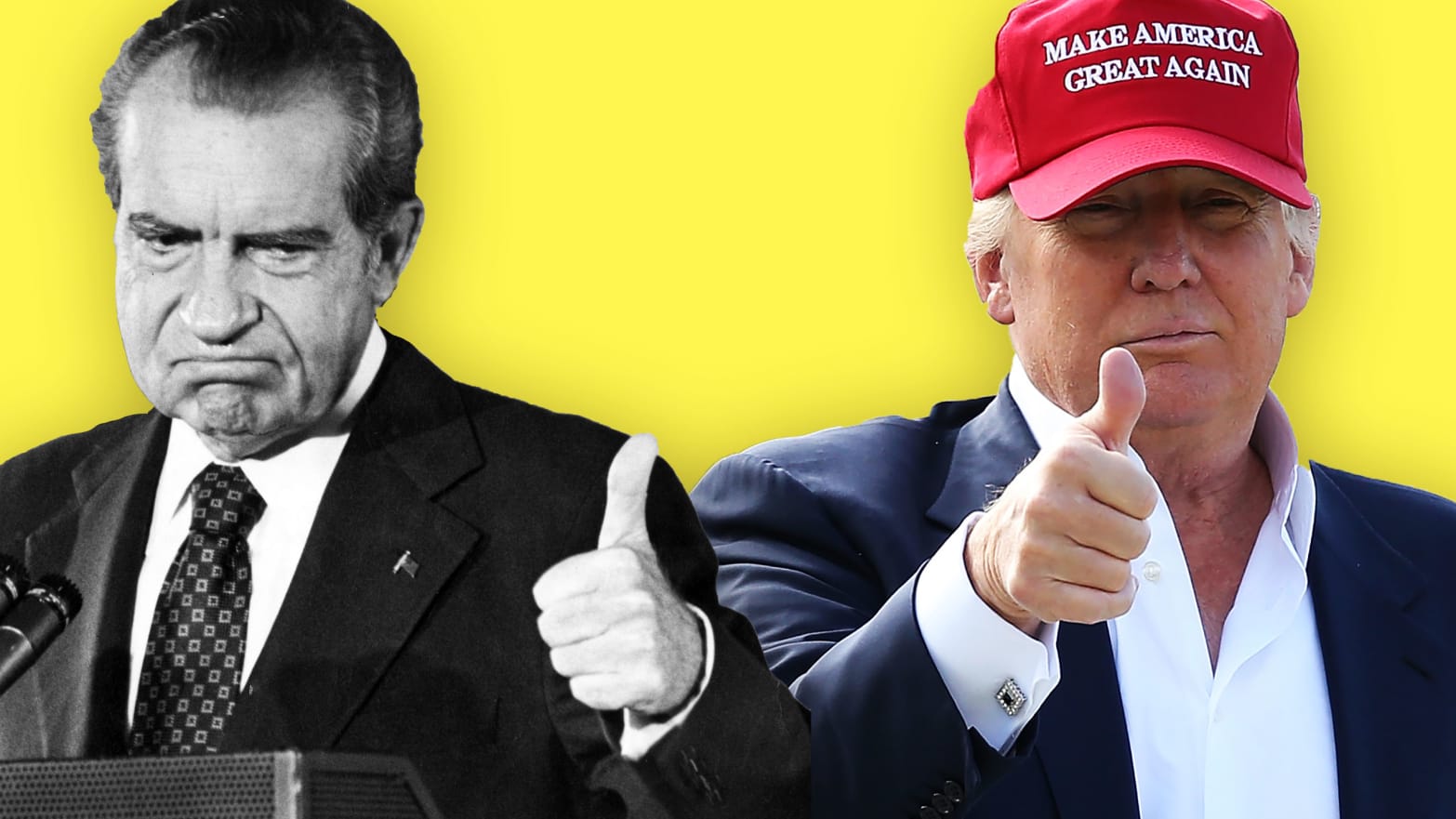

It is this situation, that may share some similarities with the Watergate investigations and the impeachment proceedings against Nixon in 1973.

But we have to go back a bit before we get to 1973.

Recordings of meetings and conversations of U.S. presidents began in 1940 during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency, following the incorrect publication of an important statement by the president about the threat of Germany at the beginning of World War II. Roosevelt’s irritation with this episode led to the installation of a system in the White House to record his press conferences or speeches as a means of countering misrepresentation of statements in the future.

The system that was installed was rarely used by Roosevelt, who recorded no more than eight hours in nearly five years, and only when he understood beforehand that the subject matter was relevant.

This system was passed on to Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson and ended with Nixon, who recorded about 3,700 hours of phone calls, conversations and meetings over 2 1/2 years, always using updated and modernized equipment. Since July 12, 1973, a year before Nixon’s resignation, recordings have no longer been made at the White House.

Although the recording system has moved from one president to another since Roosevelt, it is worth noting that Nixon rejected using it at the beginning of his term in 1969 and ordered all the devices turned off. Supposedly, only after a malicious insinuation from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Nixon reconsidered the issue in 1971, mainly because he was bothered by the presence of the note-takers who had to attend meetings and phone calls to make transcripts. These are what are now called memcons. He decided to install a completely different and very sophisticated, up-to-date system using Sony technology. In addition to the evolution of equipment, the system installed at the White House in 1971, and later at Camp David, automatically turned on whenever the president entered and began speaking in a place with microphones. This initiative has always been treated with the utmost secrecy, known only by three cabinet members and a few national security officials. Not even Henry Kissinger knew.

Today, we know the main reason that led Nixon to create such a system, besides the inconvenience of the aforementioned alternative of note-takers: the ease of recording all moments, especially the good ones, to form his historical record and ensuing publications without need for contradiction.

The hidden nature of this bold system fell apart only when, during a hearing before the Watergate investigating committee in 1973, Alexander Butterfield, one of the few cabinet members who were aware of the situation, was asked if recordings were made of the president at the White House. Butterfield told the truth; at that point, the House of Representatives issued subpoenas these recordings, a process which was challenged by the White House and ended only with a unanimous ruling by the Supreme Court in July 1974. Nixon resigned a month later.

This has been researched and reported for a long time, and Nixon did not survive the full declassification of his recordings. But what can be said today is that the resignation of the president in 1974 was not so much due to fears about the revelation of facts about Watergate that might come up in the recordings delivered to the House of Representatives, but rather about another type of facts: older ones recorded from 1971, and also at the end of President Johnson’s term, about the Vietnam War and failed peace negotiations in 1968.

The surrender of all White House recordings, which was once demanded of Nixon and ultimately determined his departure, can now also be demanded of Trump on the grounds that there is other compromising information about national security, which thickens impeachment plot.

There are no longer automatic recordings or tapes, just transcripts known as memcons. Trump obviously has more reasons than Nixon to legally oppose such a subpoena, should he decide to go down that road. But the risk is there and will last until the 2020 elections if the Democrats can keep the circus going.

Recommended soundtrack to follow the impeachment: Jimi Hendrix’s “Little Wing” or Simon & Garfunkel’s “Blues Run the Game.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.