Polarization reduces space for debate. There is a “tribalization” of opinions.

The first way to understand the current situation in the U.S. is the way its president, Donald Trump, presents it in his State of the Union address. Triumphalist: “The vision I will lay out this evening demonstrates how we are building the world’s most prosperous and inclusive society.” The next day Trump was acquitted of the two impeachment charges filed by the House of Representatives: abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

The second way is how professors Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman present it in their latest book “The Triumph of Injustice,” published a few weeks ago by The New York Times. For the first time in the last century, in 2018, the 400 richest people in the U.S. (0.001% of the population) paid a lower effective tax rate than the working class. Successive Republican fiscal reforms (under Ronald Reagan, George Bush and Donald Trump) have changed the rate from 70% to 50%, and from 50% in the 1980s to the current rate of 23%.

This data provides us with a third way to look at the American situation, one that Joseph Stiglitz reflects in his book “People, Power, and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent.” He argues that it is fair that those who are able to pay more should contribute more. Full stop. But what is happening is that those at the top of the American pyramid are paying a lower tax rate than those with lower incomes. Trump’s fiscal reform, which increases tax rates for the majority of the middle class to finance tax reductions for corporations and multimillionaires, has become perhaps the worst tax legislation ever put in place (in addition to increasing the public deficit).

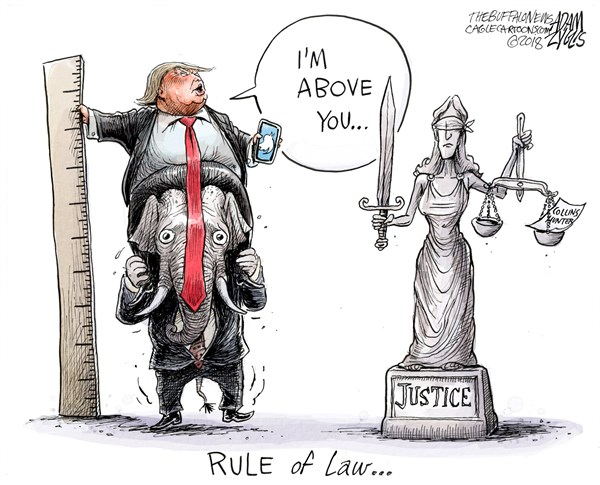

None of this reality emerged in his State of the Union address, however, which had the characteristics of a pre-election rally, as it has seldom done before. It evidenced the age of rising polarization we’re living in; the debate between left and right (supposing one could speak like that in the U.S.) is becoming, via Trump, a loud exchange of insults. In which statements and raucous tweets, freely thrown about, leave little room for a change of heart. And what makes this current situation particularly worrying is that the space for debate appears to be disappearing. Someone has spoken of the “tribalization” of opinions. And not only of political opinions, but also economic, social, philosophical, etc.

The breakup of institutional formalism in the State of the Union address this year (Trump didn’t shake hands with the speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi; she blatantly ripped up a copy of the president’s speech in full view of television cameras; various Democratic members of Congress walked out, etc.) has been more poignant than the content of the speaker’s words. It was much more about dramatization and partisan outrage than messages about the future. In his book “The Reactionary Mind,” the historian of ideas Corey Robin argues that the American president is a textbook conservative, “inside a right-wing tradition that has been circulating since the reactionary response to the French Revolution, to the anti-democratic liberalism of Hayek; the deregulatory fervor of Reagan to the despotic legalism of Carl Schmitt; the racist authoritarianism of Nixon to the anti-elitism of Sarah Palin.” In another joint publication entitled “El Síndrome Trump” (“The Trump Syndrome”), its authors question 16 social scientists (Wendy Brown, Stiglitz, Adam Tooze, Robin, Nancy Fraser…) about the idiosyncrasies of the Trump phenomenon. They arrive at the following conclusion: On Nov. 8, 2016, the U.S. woke up in the ICU. A multimillionaire B-movie character in the nation’s public eye, without political experience, or any apparent skill in anything other than the ability to find an opening in the media with his outbursts and shameless use of demagoguery, had won the election against all odds with a chauvinist, anti-immigration, anti-elitist and markedly nationalist message.

In nine months he could go on to win it again.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.