Filling the Void in Global Governance for a Stable World Order

(Japan) on 20 August 2020

by (link to original)

In the face of this global crisis, many nations have seen their lifestyles destabilized, and the crisis is putting pressure on the fragile seams of global governance. A prime example of this is the U.S. and China colliding over hegemony in the World Health Organization, followed by the U.S. announcing that it was withdrawing support for the organization.

America Turns Its Back on the World

Are other nations just going to stand by and allow the collapse of order? That will only lead to an erratic world in which countries clash in pursuit of short-term and short-lived gains. Needless to say, business and investment-related risks would also increase, triggering an economic headwind.

Instead, every country should find a path to cooperation and, even if only a little, begin filling the void in global governance. Nations should respect the rules, share the burden, and work toward long-term gains. Given the fact that global issues such as the environment and health care are becoming even more pressing, it is clear that cooperation is the road nations intend to take.

Postwar global governance has developed into a two-story structure. The first level consists of international institutions such as the United Nations, the World Bank, and the International Monetary Fund, institutions established under law that act as a backbone. These institutions were established in the aftermath of World War II with the intent to promote international cooperation.

The second level is a framework in which influential countries address global issues, as is exemplified by the Group of Seven major industrial nations, established in the 1970s, and the Group of 20 industrial and emerging-market nations, whose presence became more prominent after the 2008 financial crisis. Each of these frameworks was led by the U.S., which, while pursuing its own interests, held the world together by keeping an eye out for each country and stepping in when necessary.

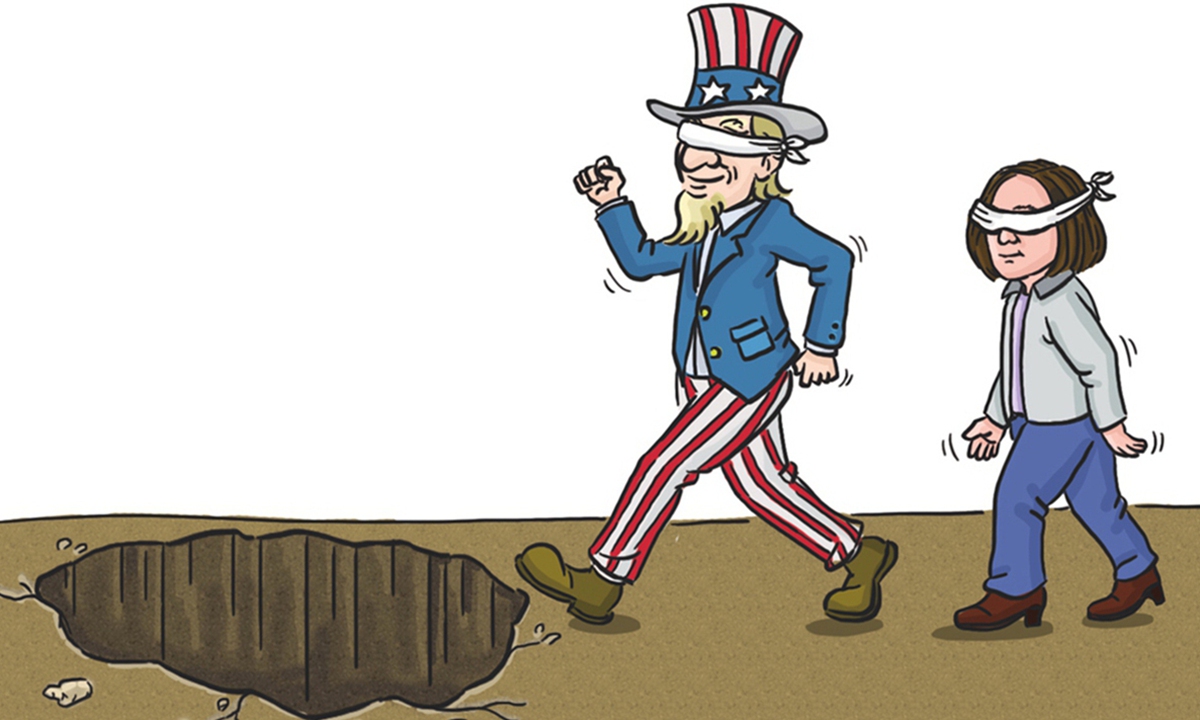

President Donald Trump has turned his back on that role. Since Trump took office in 2017, the U.S. has announced its withdrawal from several international agreements, including the climate-change-mitigating Paris climate accord. It was also the U.S. that rejected the appointment of committee members to oversee dispute settlement, thus rendering the World Trade Organization inoperable. Even the G-20 finds itself at a standstill in the face of the U.S. and its “America First” policy.

While a considerable amount of blame falls on the Trump administration, we cannot ignore the subcurrent of shifting dynamics due to China’s rise as a global power and the relative decline of the United States. Already weary from facing domestic problems such as the decrease in manufacturing and the widening economic gap, the American people want to distance themselves from global issues. Regardless of the outcome of the presidential election this November, it is likely that this reality will not see much change.

In that case, assuming the U.S. continues its limited engagement, the world will need to consider how it will go about global governance reform.

It is not realistic to visualize a world order led by China. Although China took the offensive in response to the COVID-19 pandemic with its “mask diplomacy,” according to the most recent U.S. Gallup poll, the number of people who acknowledge China’s leadership capabilities is still less than those who acknowledge America’s leadership, despite the latter currently being at an all-time low. Moreover, China’s suppression of free speech in Hong Kong left democratic countries with the impression that China is simply too different.

To protect the current international order founded on freedom and democracy, countries which share the same values will have no choice but to step up. Japan, the U.K. and Germany will have large roles to play. In order to fill the void left by the U.S., the remaining G-7 countries must come up with a strategy, reconcile their interests, and start laying the foundation for international consensus building.

Revitalizing the G-20 is also crucial in putting that plan into action. Although currently at an impasse, a framework that brings together the leaders of the countries that constitute 90% of the global economy is invaluable. Even if the G-20 cannot compel Trump to change his “America First” mentality, it would be in a position to deter protectionist policies and urge international cooperation in certain areas.

Relying on the Cooperation of Like-Minded Countries

The G-20 should be firm when it comes to holding countries, even China, accountable for respecting freedom, democracy and convention. It could even propose constructive ways to bridge the gap between the feuding China and the U.S. Yet, it is unfortunate that many nations seem to have already given up.

Even a smaller coalition of like-minded countries designed to address specific issues could serve as a crutch to the weakened global governance. For example, Singapore and New Zealand signed an agreement to maintain trade relations even during the coronavirus pandemic, including the trade of essential goods, and it was later signed by 10 additional countries. In 2019, Germany and France founded the Alliance for Multilateralism, an alliance of countries founded on respect for international law in the advocacy of multilateralism.

Two problems that will arise in the near future are the issue of the WHO’s budget, given that the U.S. has suspended funding, and dispute settlement in the WTO. Several countries should step forward to take on these responsibilities, save global governance from collapsing in whichever areas possible, and seize the opportunity for reform.

World order led by the U.S. and its overwhelming influence is coming to an end, and a more multilateral governance framework is necessary. What is the smoothest way to transition? On what philosophy should we build this new framework? Soon enough, many countries will have both their resolve and imagination put to the test.