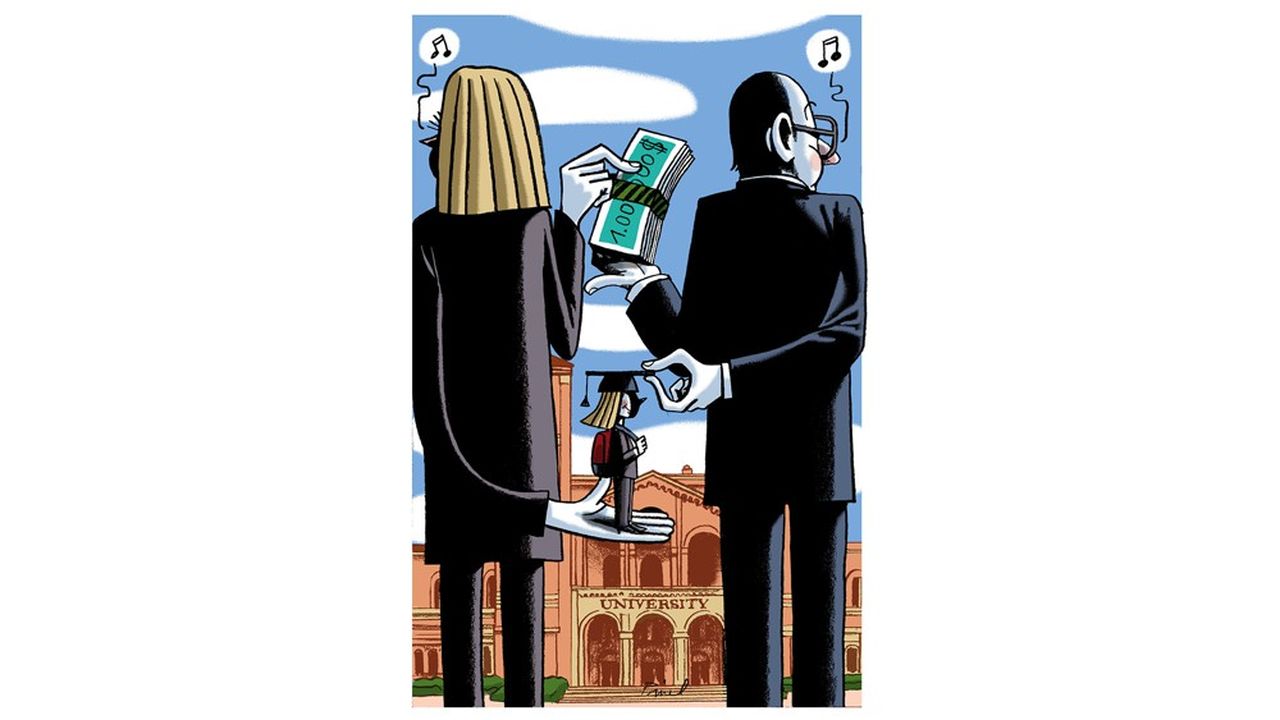

Wealthy families have benefited from large-scale fraud to get their children accepted to prestigious American universities. However, with institutions constantly seeking donations, the line between lawful practices and corruption is sometimes tenuous.

At the end of the 19th century, the rail magnate Leland Stanford had the ambition to found a university in California that could compete with the prestigious institutions of the East Coast. So, the tycoon went to the breeding ground of the American aristocracy, Massachusetts, to seek advice from the president of Harvard University, an institution which was more than two centuries old by then. “How much would it cost to create a world-renowned university?” he asked. “No less than $5 million,” the other replied. “I think that’s within our means,” Stanford concluded.

This story is still told to students visiting the Stanford campus. But it has taken on a particular significance since a large-scale fraud was exposed, revealing how dozens of wealthy families — actors, lawyers, investors — had paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to crooked consultants to get their children accepted to prestigious universities (Yale, Stanford, Georgetown, UCLA, etc.), by greasing the palms of intermediaries or tampering with exams.

Non-Academic Criteria

Although the case has caused quite a stir in the United States, it has not really come as a surprise. “This is infuriating for parents and students who chose to play by the rules in seeking college admission — or had no choice but to do so,” summed up a New York Times editorial. “But no one should be under the illusion those rules are strictly meritocratic.”

Unlike admission practices in many European countries, major universities in the U.S. indeed favor admission criteria that are not strictly academic. The aim is to guarantee a certain diversity of student profiles, paving the way to a form of subjectivity, indeed a lack of transparency.

Discrimination lawsuits launched by Asian students in 2017 brought to light the fact that special treatment was given to certain categories of candidates at Harvard — those belonging to minorities, as well as children of alumni, relatives of donors, children of employees, and top athletes.

Bonus for Alumni Children

The top American universities would undoubtedly like to have us believe that excellence cannot be bought. But for them, the issue of money is of ongoing importance. And the line between lawful practices and corruption is sometimes tenuous. Some derive up to 40% of their budget from “endowment,” a type of internal investment fund that collects the bulk of donations and invests them to yield a profit.

Thus, they choose to give preferential treatment to close relatives of alumni who have a reputation for being more generous. So-called “legacy students” can form up to 30% of the student body at major universities, with Harvard accepting the highest number.

Similarly, while funding a building or a library does not officially confer any rights, it can facilitate entry through what consultant Rick Singer, involved in the fraud, has nicknamed the “back door.” “There is a front door, which means you get in on your own,” he explained in court. “The back door is through institutional advancement, but there’s no guarantee. And I’ve created this side door in to offer a guarantee to families.”

“Affirmative Action” that Favors the Most Privileged

While using the “side door” option is considered corrupt, in contrast, the “back door” option does not pose any problems. As the attorney for the District of Massachusetts belabored last month, “We’re not talking about donating a building so that a school is more likely to take your son or daughter. We’re talking about deception and fraud.”

According to Dan Golden, author of a bestseller on the subject (“The Price of Admission,” Penguin Random House, 2007), “at least a third” of those admitted to the most elite universities in the country “benefited from preferential treatment during the admission process.” So much so that he describes a kind of “affirmative action” that favors the most privileged and deprives the middle class of access to which they could at least be entitled. This type of affirmative action is much stronger than the oft-criticized one for minorities.

His book is full of examples like that of former vice president Al Gore, who studied at Harvard, and whose four children were later admitted to the university despite inconsistent grades. Or that of Robert Bass, Texan oil billionaire, who donated $25 million in 1991 to Stanford University, where his daughter was accepted seven years later (she was the only one from her high school). Or even that of Jared Kushner, son-in-law and advisor to President Donald Trump, who gained admission to Harvard despite average grades according to his former high school, a year after his father made a donation of $2.5 million. His younger brother followed him there ten years later.

When Trump’s supporters denounce, at their president’s call, a “rigged” system, when they applaud his anti-elite diatribes, they are also thinking of this system of privilege. It is ironic that they chose a president whose three children were admitted to the prestigious University of Pennsylvania, his alma mater, and where he would have made sure to donate $1.5 million.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.