Censorship Cases: A brief Chronicle

Censuring the arts is not exclusively the decision of some authorities in our local setting. Following are some of the most significant cases of censorship in the world.

The organizers of the Salón de Julio, one of the major arts competitions in our country, invited native and foreign artists residing in the country to participate in the 2011 session.

However, artists working on sexually explicit content were not invited. Or, in the words of the announcement:

“The theme and technique are within one’s right. However, proposals containing sexually explicit language and/or graphics will not be accepted.”

Following is a brief chronicle of five cases in which censorship, as in the case of the Salón de Julio, has tried to silence voices that, because of subject matter, make the establishment uncomfortable.

Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Last April, after opening the Sharjah Biennial, one of the most important on the Asian continent, the authorities ordered the removal of a work they considered blasphemous and obscene.

The work by Mustafa Benfodil is an installation that condemns the systematic violations suffered by women in Algeria at the hands of religious extremists during the 10 years of their civil war. The authorities (all male authorities, of course) consider the work offensive because of its sexual content and because it mentions Allah, a blasphemous violation, from their point of view.

Washington, D.C., United States

A scandal erupted last November, involving the National Portrait Gallery, because of a video made in 1986-1987 entitled “A Fire in My Belly” by David Wojnarowicz.

The work in question was censored and the museum managers were forced to remove it from the exhibition, “Hide/Seek: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture,” at the behest of certain opportunists who considered the work blasphemous.

“A Fire in My Belly” is a denunciation of the addiction to violence in our cultures, in particular, the American and the Mexican. It copiously illustrates the daily life of a small Mexican city, with its traditions and miseries. It also includes, at various intervals—and shows, for a total of 19 seconds—the image of a plastic Christ partially covered by ants.

Taken out of context, the image loses its argument for spirituality and its cry of empathy for the vulnerable. Taken out of context, the image is manipulated into the banner of yet another campaign against the arts, in general, and against freedom of expression, in particular.

Washington, D.C., and Cincinnati, O.H., United States

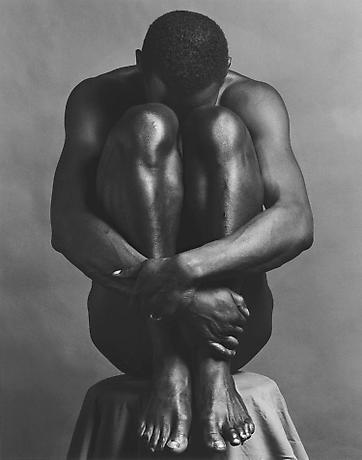

May 1988. Robert Mapplethorpe’s “The Perfect Moment,” the first retrospective of the New York photographer, opens in New York. It is scheduled to travel to several other American cities.

But before reaching its third destination, the Director of the Corcoran Art Gallery in Washington D.C., under attack from extreme right-wing politicians, is forced to cancel the show, at the risk of losing the government’s contribution to its annual budget.

Similarly, in April 1990, and after the show was presented in several cities without further commotion, the director of the Contemporary Arts Center of Cincinnati, Ohio, is imprisoned, just before the opening of the exhibition.

The pitched battle that followed during the next few years in all sorts of arenas, from the street to the press, from the courts to the Senate and Congress, from the museums to the pulpits, would leave an indelible imprint on the psyche of American society.

What was at stake was nothing less than the sacred First Amendment to the Constitution of the country, guaranteeing liberty of expression. This is one of the values most rooted in the collective conscience of the country, but one which many try to alter.

The origin of this confrontation was based on the context of six, sexually explicit photographs. Indeed, these works were much more offensive than what might be understood by simply calling them pornographic.

Considered “criminally offensive,” the force of these photographs and of Mapplethorpe’s work in general, lies not in what they show, allegedly obscene, but, rather, in the revolutionary manner in which it shows the content in question.

The photographs are, above all, subversive, proposing and updating concepts of a new relationship between bodies of different races and of the same gender, and doing so through images imbued with a powerful and omnipresent majesty.

The power of the photographs lies in their power to provoke, to expose all kinds of internalized fears in a society marked by racism, misogyny and homophobia.

They force us to face what we do not want to see. They demonstrate the double standard that blinds and permeates us in our day-to-day lives.

Entarte Kunst [Degenerate Art], Germany

This was the appellation given the exhibition organized by the Third Reich in 1937, which toured throughout Germany. Degenerate art became, ironically and paradoxically, the most visited art exhibition of all times in that country.

The show is composed of more than 650 pieces. But the reality behind this huge number of works is different: 20,000 works of more than 200 artists—among them the greatest of modern German artists, taken from museums, private collections and artist workshops—are expurgated to be destroyed or sold abroad.

The exhibition was intended to inform the German public, in general, what the Nazi State considered to be degenerate art, unacceptable, corrupt, Zionist, Bolshevik and/or the product of sick minds.

It included masterpieces by Expressionists, Fauves, Cubists, Dadaists, Surrealists, Beckmann, Chagall, Dix, Ernst, Kandisnky, Klee, Kirchner, El Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, Mondrian, some of the geniuses who mark the history of 20th century art and who witnessed their works being censored and destroyed by national socialism.

Their sin? The usual: being different, groundbreaking, innovative, subverting the established order. The country had to be cleansed of all representation that did not extol the Aryan race or the values of the Third Reich. These values could be represented only realistically and, of course, by exalting the virtues and values considered to be Germanic.

The avant–garde artists residing in Germany, and later, in German-occupied territories were forbidden to create, to produce any work that did not adhere to academic realism. Censorship was absolute.

For decades, Nazi Germany, along with the Soviet Union and the Soviet-block countries, as well as Mao’s China and Castro’s Cuba underwent a systematic censorship that claimed thousands of lives and severed all creative expression divergent from that established by the State.

What is the purpose of prohibiting art that explicitly deals with sex or current political issues or religions that are treated in a suspicious way?

Who has the right to define and regulate what we can see, listen to, communicate and create?

Could it be, perhaps, that the citizen, who is able to vote is not capable of deciding for himself?

Michelangelo’s “Last judgment,” Velazquez’s “Venus at Her Mirror,” Goya’s “Naked Maja,” and Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon” are examples of masterworks that were, in their day, considered indecent.

When the organizers of the Salón de Julio prohibit the participation of every sexual content work, they silence and put conditions on certain visual languages by considering them uncomfortable or indecent.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.