Poverty, violence, gangs: The city of Oakland, located on San Francisco Bay, has until now suffered an unenviable reputation. However, it is in the process of becoming a newly fashionable place. Boosted by the excessive salaries of Silicon Valley, the real estate market in Northern California has boomed in recent years. Result: Residents of San Francisco Bay are moving en masse, driven away by those better off than themselves.

While the very rich buy or rent apartments with views of the Golden Gate at top dollar, San Francisco’s middle class is turning toward the hitherto little-desired Oakland.

In terms of real estate, San Francisco and its neighbor have thus become the most dynamic American cities in the country, according to the specialized website Trulia. In Oakland, nearly seven out of 10 homes sell in less than two months. On the other side of the Bay Bridge, in San Francisco, it’s even more: 74 percent. The inhabitants of this metropolis of 800,000 are fleeing a market where the average sale amounts to $1.2 million. In Oakland (population just over 400,000), housing still costs half the price ($599,000, on average).

Food Trucks, Folk Concerts and Hipsters

Dubbed “the new Brooklyn” for several years now, notably by The New York Times, it should be noted that the comparison makes sense. On weekends, the downtown streets of this third industrial port on the West Coast are filled with a young and trendy set. First Friday has become the unmissable “hipster” event. Getting off the BART, the local subway, they come straight from the heart of San Francisco. Food trucks now invade the central Telegraph Avenue, closed for 10 blocks for the occasion. Barbecue pork sandwiches, burritos and local-organic vegetarian pies are snapped up to the strains of hip-hop, folk or even klezmer concerts.

How has Oakland, considered by the FBI as the second most dangerous city in the United States after Detroit, become the new promised land of San Franciscans? Researchers from the University of California at Berkeley, a neighboring city, are looking into the matter.

Dr. Miriam Zuk and her team have mapped out the region’s urban displacements. Questioned by Rue89, the researcher, a graduate of the prestigious MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), confirms that the phenomenon is caused by the stupendous six-figure annual salaries of the advanced technology companies.

“Wages in Silicon Valley do impact real estate prices. And it is not a localized phenomenon. Real estate markets are interconnected. A significant population displacement is seen in the region and it is expected that this trend will intensify in the future. Many areas risk being affected.”

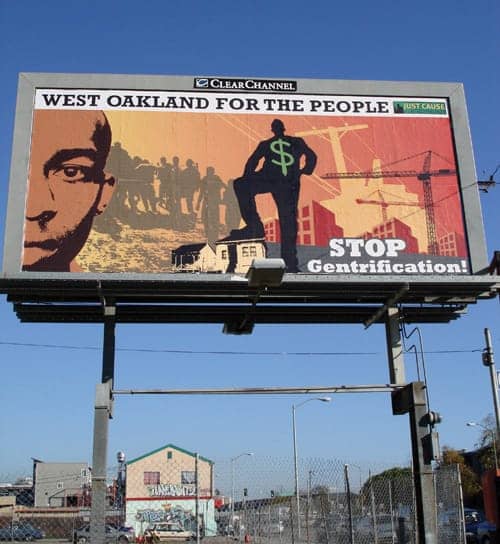

Gentrification: Good or Bad?

When she evokes the phenomenon of gentrification, Miriam Zuk speaks of “risk.” For, if the arrival of households with strong buying power is good for the local economy, it inevitably impacts the lowest wages.

“The subject is widely debated. Is gentrification good or bad? For whom? Who are the residents of these areas at risk of gentrification, and will they have the means to stay there? We see many areas that are becoming too expensive for households with modest incomes.”

The Berkeley researcher and her team are now focusing on how to guide this transition. Legal counsel, rent control and building controlled-rent housing are under consideration.

“It is important to consider the type of housing that is built so that cities can invest in homes at affordable prices and thus maintain some diversity.”

The neighborhoods most affected by the phenomenon of gentrification are in northwest Oakland, about 20 minutes from downtown San Francisco. Formerly infamous, this part of the city, which teemed with addicts and dealers, has changed dramatically. Harry, a 61-year-old African-American carpenter, saw part of his family grow up there, before himself moving into the family home 51 years ago. This tall, thin man with a drawn expression recalls:

“Fifteen years ago, the neighborhood was a place for drug deals, with all the violence and insecurity that that entails. Today, it has completely changed — children play in the street, new residents have moved in, bringing a little diversity.”

“Our Family Needs This House”

Sitting on the steps of his house, under a stifling sun, Harry takes the time to tell us his story. He grew up in East Oakland neighborhoods, where gentrification is far off. The house in North Oakland has been in the family for some 50 years. Bought for $60,000 at that time, it would be worth 10 times more today. He confided to us that he discussed selling it with his wife. But they decided that the property will remain in the family: “Our family needs this house.”

Quickly, the discussion turns to the issue of race. Because, in the United States, more than elsewhere, the purchasing power of a household is generally tied to the origins of the people who comprise it.

Harry, who advocates for a multicultural society, sees the arrival of the “whites” — a term synonymous here with a population with comfortable incomes — in a good light. It takes all kinds to make the world, he assures. But this father of five — the eldest of whom has a master’s degree, he tells us with pride — regrets that a number of “historic” residents have been thus pushed to leave their hometown.

Anger indeed reigns in the heart of this population, a collateral victim of Silicon Valley, where money pours down. Some blame the politicians for this two-speed society; others blame the media.

Younger, Whiter, Wealthier

A few blocks away, Brock, 33, almost feels guilty for being “well-born.” This writer, with piercing blue eyes, arrived in the neighborhood a dozen years ago with his wife. Originally from North Carolina and Minnesota, they became property owners in Oakland after five years, shortly after the housing bubble burst. Brock receives us in his eruditely decorated living room and explains: “We bought here because we liked the neighborhood and prices corresponded to our budget. After the housing crisis, many people lost their homes, mainly African-Americans, opening the doors of the neighborhood to younger, whiter, wealthier people, like us.”

Curious by nature, and a history buff, he asked himself — and continues to do so — about the upheaval taking place in his neighborhood and its sociocultural effects. Recalling the wave of protest that arose from the “historic residents” — a notion he is hardly fond of because it hits a little too close to home — Brock began to go through the history of the neighborhood, as he explains in the quarterly magazine Boom, published by UCLA, to better understand its precise “historical” evolution.

The Share of African-Americans Halved

In 1980, 84 percent of the neighborhood was African-American; in 2010 it was 44 percent, he explained. In the 1940s, nearly all the owners were “Caucasian,” as African-Americans didn’t have access to property. He recalls that the story does not begin in the 1970s, and that it was not that long ago that black American populations were clearly and officially subject to segregation.

Faced with this phenomenon of the eviction of a fringe of the population, he feels powerless: “The local authorities do not have the means to implement effective policies to protect the inhabitants. And on the federal level, there is no will to support low-income people with respect to real estate. So I sit in my house, which I bought at the right time by accident, and my wife and I, who have the luck to have a good level of education, families who can support us, who are white — it helps in the United States! — and who would like to be the kind of people who contribute to a city where people from all walks of life live, we do not know how.”

Brock does not intend to leave his neighborhood, to which he is attached. Even if his house, as he believes, is now worth over one and a half times the price at which he bought it. A beautiful potential capital gain, but an amount insufficient for moving to a more popular neighborhood, in any case.

“Real Estate Also Collapses”

Jonathan, 38, is not going anywhere, either. Originally from the region, he chose to buy in the neighborhood in 2006 mainly because it was ideally located between San Francisco and his family in the East Bay. This computer engineer, who gave up his car for his bike a few years ago, said: “These last four years, many things have changed, many restaurants have opened. It is now possible to go to the stores on foot.”

Owner of several properties that he rents in part — including one floor of his own home — he knows, acutely, that Oakland’s gentrification is financially favorable for him. He also says that he could easily increase his rents. And he doesn’t hesitate, moreover, to put his house on Airbnb when he’s gone for long periods.

But Jonathan likes to live in an area rich with social and cultural diversity and values the good relationship that he has with his neighbors. Like many of them, he regrets that some “historic” residents are pushed out by unscrupulous owners. Confronted with the euphoria prevailing in San Francisco Bay, he prefers to keep his feet on the ground. “Here, everything revolves around money. I try not to let myself be carried away by the prevailing hysteria. Real estate goes up, it goes down. It collapses, too ….”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.