A series of murals painted inside a San Francisco school in 1936 may be destroyed now that the San Francisco Board of Education has deemed them to be racist. For legal expert Isabelle Feng, the decision demonstrates a lack of understanding of the work’s artistic meaning and violates artistic freedom.

An open house for the public held on Aug. 1 at George Washington High School in San Francisco attracted more retirees, historians and artists than students. They showed up to view “The Life of Washington,” a mural painted by artist Victor Arnautoff in 1936.

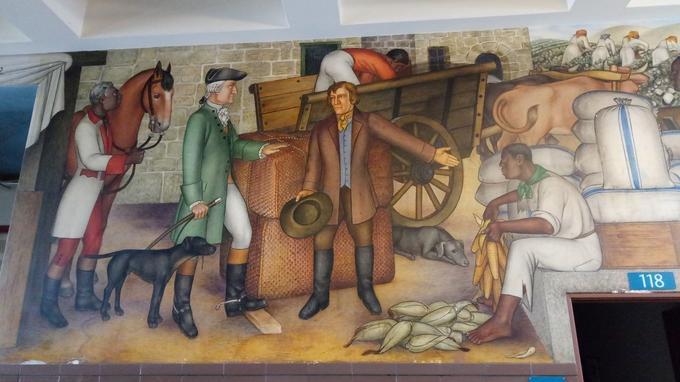

It’s very possible that these curious attendees will be the last people who have a chance to take in the work that has adorned the public school’s entrance hall for 83 years. Once viewed as educational and innovative, today the mural has fallen into a state of disgrace, being at the center of an intense national controversy. The city’s board of education unanimously voted to destroy the painting in an effort to combat racism. Among the 13 panels of this 150-square-meter mural (approximately 1,615 square feet), which primarily depicts Washington’s life, the body of a Native American can be seen along with a number of black people working in fields. The painting also portrays three French soldiers who are clearly present to back the fight against British colonizers.

To justify its decision to erase the mural or, more accurately, to paint it over in white, the board of education asserted that students need to be educated in a “safe” environment and “shouldn’t be exposed to violent imagery” because, in the words of the board of education’s vice president, these images are “degrading.” Considered by some students to be a source of racist violence, the mural is expected to be removed.

This is what makes the controversy so absurd: by portraying the fact that an American founding father owned black slaves, the Russian born artist intended to condemn one of the darkest aspects of U.S. history, slavery and racism. Working under the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, Arnautoff, a Communist, was known as a left-leaning artist. When an anti-racist work created by a leftist painter becomes the target of an attack by leftist activists under the guise of combating racism within a period of less than 100 years, it can be said that political correctness in the United States has reached a new, spectacular level.

Should the past be erased in order to make the present easier to stand? Can we give ourselves the right to condemn an artwork from the past just because it’s offensive to people today? It’s obvious that in the land of Uncle Sam, a significant portion of the population leans in favor of answering yes to both questions. Using the same line of thinking, in the not too distant future we could call into question whether it is appropriate to change the name of Washington State or ban “Gone With the Wind,” whose author, Margaret Mitchell, minimized, if not glorified, slavery.

Despite the mural’s imminent destruction, not all hope of preserving it has been lost, and a petition is currently being circulated by a group of artists and university professors. The New York Times art critic, Roberta Smith, asks, “Who owns a work of art?” and quotes Mexican artist Diego Rivera, who wrote, “If someone buys the Sistine Chapel, does he have the authority to destroy it?”

It’s equally interesting to note that in the 1960s, the Black Panthers were the first to advocate for the destruction of the frescoes and even commissioned a young African American artist, Dewey Crumpler, to repaint the panels so that they would feature “positive imagery of people of color.” Crumpler, who understood Arnautoff’s political message, turned down the commission. Today, Crumpler has called for the preservation of the frescoes, just as the influential NAACP has, in a refusal to allow African American history to be whitewashed.

This episode is only the latest in a long series of events in which the issue of race, a word that was removed from the French Constitution in 2018, has become mixed up with art. One can recall the edifying New York exhibition of white artist Dana Schutz, who, in a bold move, took inspiration from black suffering in painting “Open Casket,” a work based on the murder of African American teenager Emmett Till by white supremacists in 1955. The work upset members of the black art community, who asked that it be destroyed on the pretext that white artists can’t understand black suffering and only profit from it. Schutz’s critics appeared to be saying that skin color determines an artist’s scope of creativity. And yet, when actor Adrian Lester took on the lead role of Hamlet in a Parisian theater and did not wear white makeup as was customary in the 19th century, Shakespeare fans hardly seemed troubled by the Prince of Denmark’s literally black face.

This leads us to believe that, on the other side of the Atlantic, freedom of expression and artistic license still take precedence over feuds between communities, as demonstrated by the blackface controversy that erupted at the Sorbonne last spring when anti-racist organizations boycotted a play by Aeschylus because the actors wore masks depicting black characters. The accusations of racism were all but unanimously rejected. The art community severely criticized the boycott as fundamentalist and identity-based censorship, while the French minister of culture condemned the protesters for infringing on artistic freedom. Perhaps such positions are distinctly French? Demanded by American left-wing activists, the destruction of the famous frescoes was, after all, considered to be in bad taste by the French left. In Le Monde Diplomatique, Serge Halimi characterized those who decided to remove Arnautoff’s work as “The Taliban of San Francisco.”

As for the frescoes’ defenders, events that unfolded in 2015 at the University of Oxford may offer some reason for optimism. Originally launched by a group of students in South Africa, the “Rhodes Must Fall” campaign called for the removal of a statue of Cecil Rhodes, a philanthropist and businessman who epitomized British colonialism, from the campus of Oriel College in order for there to be “better representation of non-white culture” at the institution. Meanwhile, the Islamic State was waging a campaign to destroy historical monuments in Syria, Libya and Iraq, which likely influenced Oriel College’s ultimate decision to keep the statue in place despite the request of the “Rhodes Must Fall” group. The statue of the 19th century imperialist still stands at the college today.

Isabelle Feng is a researcher at the Perelman Centre for Legal Philosophy of the Free University of Brussels.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.