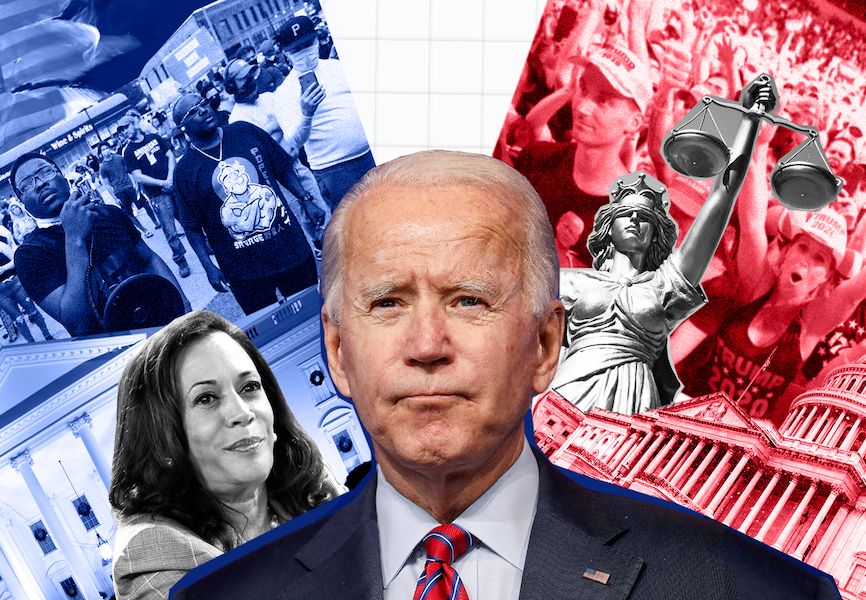

Will Joe Biden keep his promise to reunite the United States by extending a hand to moderate Republicans, or will he remain firmly on the partisan line to please the left of his party?

The Biden presidency already seems like a “deja vu” of Barack Obama’s. This is promising for partisan Democrats, but less so for those who hope for the reunification of a country so deeply divided.

In the hours and days following his inauguration, Biden signed executive orders at an amazing rate. In fact, in one week he had already signed more than his three most recent predecessors combined for the same period.

And all of these laws are designed to please the left-wing base of the Democratic Party: An end to the construction of the wall on the Mexican-American border, the suspension of the deportation of undocumented migrants and the withdrawal of the permit for the Keystone XL oil pipeline, to name just a few. These decisions had been widely telegraphed by Biden’s team, and therefore should not have come as a surprise to anyone.

The first real test of Biden’s promise to “reunite America” — the flagship commitment of both his presidential campaign, and then his inaugural speech on Jan. 20 — came after the signing of these orders, when the time came for him to submit his first major project to Congress: an enormous economic aid proposal.

A Partisan or Bipartisan Plan?

Unlike an executive order, a bill cannot simply be adopted with the signature of just one man. It requires the two chambers of Congress agreeing on the bill, which is then signed by the president. And following the 2020 election, the two chambers are almost exactly balanced: There is a Democratic majority of 222 to 212 in the House of Representatives, and 50-50 split in the Senate, which the Democrats officially control thanks to Vice President Kamala Harris’ ability to break any deadlock with her deciding vote.

Because of this dynamic, Biden faces a difficult choice: either counting on cooperation between the two parties, or getting his program adopted on a strictly partisan basis. Both approaches entail risks for the new president.

The first option — accepting a helping hand from more moderate Republican senators such as Mitt Romney, and agreeing to a more modest and specific aid plan — would mean frustrating the left wing of his party, which is currently eager to control the political machine in Washington.

With the second option, Biden would essentially make a mockery of his own promise by relying on unilateral support from his own party to adopt the plan without compromise and without any real support from Republicans, despite it being the very first major measure to be considered by the new Congress.

Echoes of Obama

Obama rose to political star status almost instantly following his speech at the Democratic National Convention in 2004. He offered a vibrant plea for national unity, claiming there are “no red states or blue states, but the United States of America.”*

Repeating his calls for cooperation during his 2008 presidential campaign, Obama soon faced a harsher reality once in office in January 2009. The country was experiencing the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression — conditions which Biden literally inherits today. Obama’s first priority was to pass a massive plan for economic aid, on the order of $800 billion.

Sprawling over more than 400 pages and aiming to inject public funds into a range of programs, the plan was considered by Republicans in Congress to be too expensive and not sufficiently targeted. In a later meeting behind closed doors, reported by Bob Woodward in one of his most important books about the Obama era, the new president said to Republican leaders, “Elections have consequences. And I won.”

Obama was right: Not only had he won, but his party also had a majority in Congress. And he could argue, with good reason, that Republicans were poorly positioned to talk about fiscal responsibility, since they had supported record deficits during George W. Bush’s previous presidency.

The program of economic aid was therefore adopted by the House of Representatives in February 2009, with all of the 179 Republicans present voting against the bill. Lines of division had been drawn, and the water already poisoned.

The Climate Action Plan; the Affordable Care Act; reforms of Wall Street; reforms of the immigration system; the Iran nuclear deal: For the following eight years, not a single measure enjoyed real support from both parties in Washington. And Obama, who began his time in office with approval ratings of around 70% and a high proportion of independent and even Republican voters willing to give him a chance, ended up most of the time with ratings around the 45-50% mark, always supported by the hard core of his own party.

Clearly that didn’t stop him from being reelected in 2012, with 51% of the vote. But Obama left his successor a country even more divided than the one he had inherited. And his successor was hardly a unifying figure.

With the Democratic left wing now even more militant than it was a few years ago, if Biden governs with only the support of his party, he risks the greater political danger of eventually losing much of the center of the American political chess board, which was fundamental to his victory in November.

Since Jan. 20, furious tweets, personal insults and outrageous scheming are no longer in fashion. The tone has already improved. The question now is whether in his actions the new president will be able to distinguish himself from his immediate predecessor, and also from the one who came before him.

*Editor’s note: Obama’s actual words at the convention were, “The pundits like to slice-and-dice our country into Red States and Blue States … We are one people … all of us defending the United States of America.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.