Edited by Robin Silberman

In Washington, the crowds flock in front of the gates of the White House. They come as families: grandparents, parents, children, and among them many representatives of the African-American community. Their presence still reflects their joy, mixed with astonishment, “a black president in the White House!”.

At Monticello, Virginia, less than two hours from Washington, residence of Thomas Jefferson, third President of the United States, crowds flock too. But there is no black visitor. It is true that Jefferson, one proponent of the Enlightenment, was also a Southern planter who owned more than one hundred slaves.

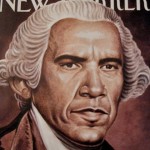

The White House, Monticello – the opposition between the present and the past – the symbol is almost too good and too simple. Yet all the polls show that the relationship between communities has changed in the United States since the election of Barack Obama, and particularly between whites and blacks. Respondents speak of a new climate, a more confident mood. African-Americans are leaving behind, for the first time, the feeling of humiliation that they have been bearing.

Nobody expresses these feelings better than the president’s wife, Michelle Obama. “Who would have thought that a descendant of slaves would one day become the first lady of the United States?” She speaks with a simplicity that has made her win the hearts of the vast majority of Americans. She is actually more popular than her husband. It is also the view of the white community toward the black community that has changed. The other day, I asked a student from the traditional elite of Boston a politically incorrect question, about what “the presence of a black president in the White House” means to her. Her answer was immediate: “But I do not see him as black, he is the President, my President and that’s all.” [Editor’s note: Quotations are translated and could not be verified as exact originals].

Since the election of Barack Obama, there is undoubtedly in the United States a calm climate in relations between communities, despite a difficult economic and social situation. But an event, though symbolic and exceptional, is not sufficient by itself to overcome centuries of injustice and humiliation. In the “Coop,” the vast library of Harvard, if you are looking for books on the African-American community, you should go to the shelf for regional studies, after studies on Africa, as if the first term “Africa” still prevailed over the second, “America.” When will studies on the African-American community join the shelves of U.S. history?

Slavery officially ended in the United States in 1862 and was confirmed by the victory of the Northern States over the South in 1865. We speak of “Civil War” because the supporters of the Union prevailed over the Confederates. But slavery under numerous and insidious forms continued, both in the North and in the South, until the end of the First World War. It wasn’t until the presidency of Lyndon Johnson and the year 1964 that the civil rights of blacks were fully recognized and marked the end, de facto, of the apartheid still prevailing in the Southern states.

Even today, statistics amply demonstrate that it is within the African American community that the rate of unemployment and prisoners is the highest… while life expectancy is the lowest. Collectively this community was able to regain dignity and hope; but among individuals, it is within this community that we find more suffering and inequality.

In the school of deserving children of the black community where she teaches in Washington, the daughter of very close friends told me how her students live in a kind of ghetto. She is the only white they know and frequently see. For them, the presence of Obama in the White House, in the city of Washington, seems so far from them, and remains largely abstract. The success of an exceptional man cannot, by itself, resolve so deep and so old a trauma, the product of slavery.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.