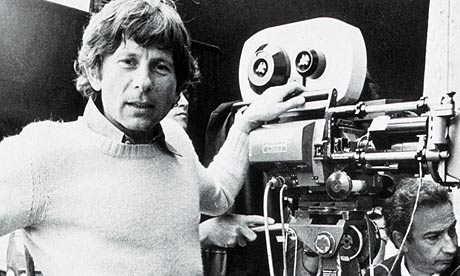

This weekend I got back from Los Angeles, where I had been following the Californian leg of Polanski’s extradition case. Polanski will not appear before the Santa Monica Superior Court, as he did in 1977 and 1978. That court no longer deals with criminal cases; these days it has the air of a sleepy and forsaken sub-prefecture, standing a stone’s throw from the sea on Third Street, between the art deco City Hall and the chic but discreet new building of the famous Rand Corporation. Thirty-two years have passed. The media circus of the day, the archive footage showing little squads of cameramen running around in their bell-bottomed trousers, will seem almost like child’s play compared to what’s on the horizon: the gridlock of satellite trucks, the breathless live reports on the 24-hour news channels when Polanski makes his inevitable court appearance.

The hearing will take place on Temple Street in the Superior Court’s huge building in downtown Los Angeles, a legal factory shaped like a bunker with minuscule windows where, from eight o’clock in the morning, half the population of this megalopolis seem to be pushing and shoving in front of the security gates before heading into the courtrooms that are piled ten stories high.

Polanski will appear in Department 100, on the thirteenth floor, before Judge Peter Espinoza, who took charge of the film director’s appeal case in January 2009. This, frankly, is something of a stroke of luck. Espinoza, with his mariachi mustache and his nice bow tie, is one of the most respected judges in Los Angeles County. He is a “supervising judge” who was named Best Judge in 2003 by the Mexican-American Bar Association and has also received an award from the Criminal Court Bar Association. He was one of four children, his mother a primary school teacher in Los Cerritos. He’s a reasonable, rigorous, attentive and courteous guy, known for his dislike of Californian societal gossip. Espinoza served for a long time as an Los Angeles County prosecutor, in which capacity he was an ardent defender of legal equality for minorities. He became a judge in 2001, was appointed rather than elected to the post, and has no personal or political reason to give Polanski a particularly hard time in court.

There’s a lot of talk here of the possibility of “probation”: a conviction combined with a suspended sentence, or even with a complete overturning of the 1978 trial, which was vitiated by the antics of the then judge, Laurence Rittenband. But the essential condition is still the fugitive’s return to Los Angeles. If the negotiations are taking place behind the scenes with the Justice Department in Washington, no deal can be made with the judge, much less with the prosecutors, until such time as Polanski returns. To be continued.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.