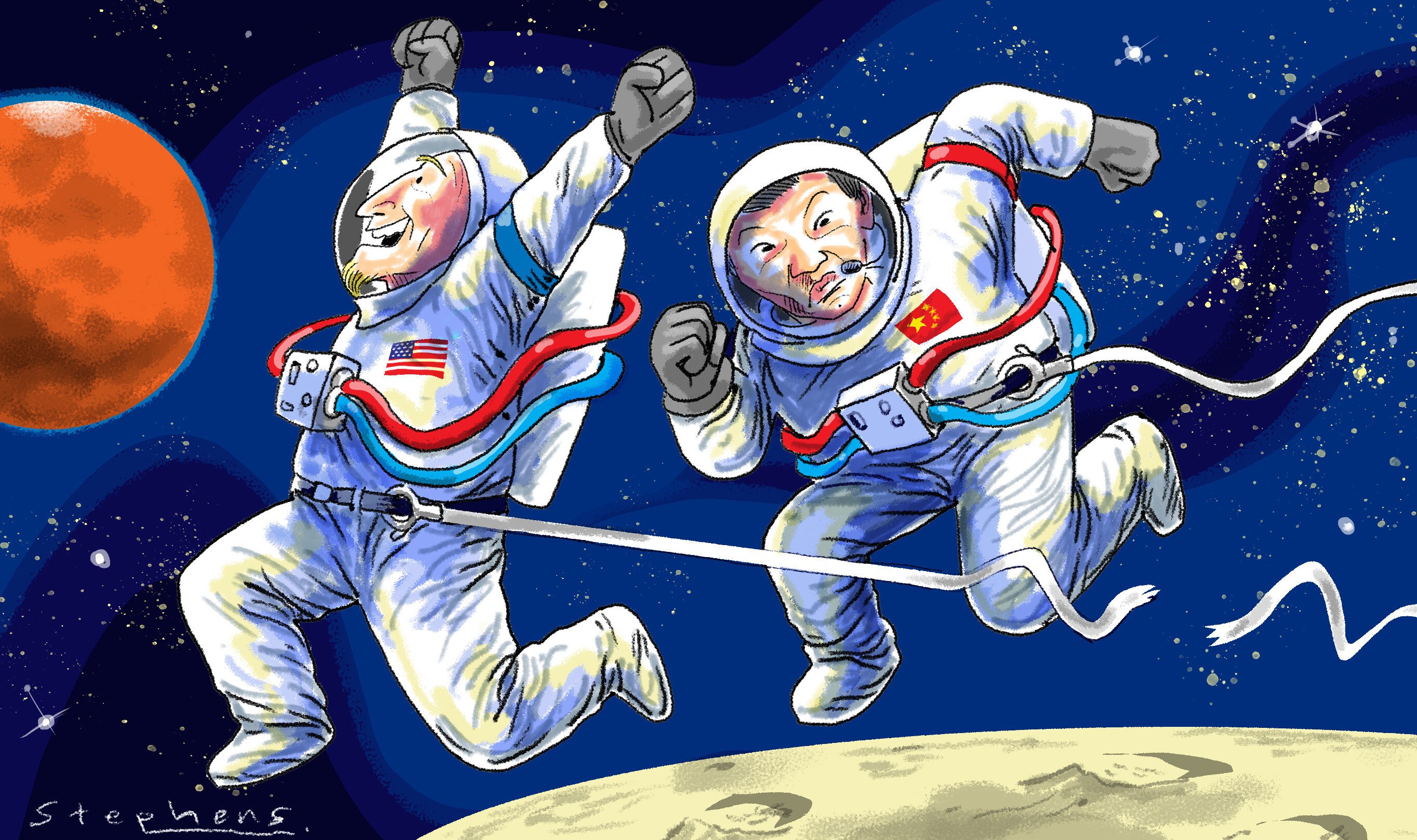

Beijing announced Saturday, May 15, that its Zhurong robot had landed on Mars. In spite of this success, there is currently no real rivalry between the Chinese and the Americans in the skies, given the lead taken by the Americans since the 1960s.

Even if no photograph sent from Mars has yet been confirmed,* the Chinese space agency has announced that its small mobile robot Zhurong had succeeded in landing on the red planet on Saturday, May 15. The technical feat is proving to be significant because the entry and braking maneuver in the Martian atmosphere is a formidable test that, up until now, only the Americans have mastered. Chinese President Xi Jinping didn’t fail to stress that, with a bit of vainglory in the congratulations that he addressed to mission officials, asserting that it was going to leave “the imprint of the Chinese on Mars for the first time,” adding, “The homeland and the people will always remember your exceptional exploits.”

This success is to be added to several others — the landing of a rover on the far side of the moon in 2019, the return of lunar samples in 2020, the placement into orbit of the first element of a space station in April, which will revive Chinese manned flights — and shows to what extent Beijing is becoming involved in outer space.

An annual budget estimated at $10 billion, numerous Earth observation satellites, a complete panoply of rockets, a program for the exploration of the lunar south pole, a satellite positioning system to rival that of the American GPS, the European Galileo and the Russian Global Navigation Satellite System: China has established itself as the world’s No. 2 in space.

Technological Delay

From there to thinking that it is in direct competition with No. 1 — the United States — there is only one step, which others have taken. However, the facts demand greater caution: For the moment, the two nations are not boxing in the same class. Simply from a budgetary point of view, NASA has an annual appropriation of $23 billion and it isn’t the sole actor in the American space field. And one must consider the Chinese successes, certainly remarkable, for what they really are: benchmarks in catching up on technological delay.

The first American astronaut flew in 1961, the first Chinese in 2003; the United States brought back more than 380 kilos (838 pounds) of lunar samples between 1969 and 1972, while China has brought back only 2 kilos (4 pounds) a half-decade later; NASA touched down for the first time on Mars in 1976 with the two Viking landers, and its first rover, Sojourner, already went back up in 1997; the International Space Station, in which the United States is a major participant with the Russians, the Canadians, the Europeans and the Japanese, has been circling the Earth since 1998 and is huge compared with the Chinese project; American scientific probes have crisscrossed the solar system and some have even gone beyond it. … To this already long overview of the gap between the two countries one must certainly add the 12 Americans who walked on the moon during the Apollo program.

Even if this demonstration is tempting, because it reproduces in the skies the geostrategic competition that we are acquainted with on Earth, the space match between the United States and China thus remains in large part a false competition. However, the two superpowers have a vested interest in being regarded as direct competitors. Washington makes use of it to justify a costly manned lunar program: Donald Trump, who ordered it, could not accept that the first to return to our satellite should be Chinese. Beijing, for its part, is delighted to be perceived as a true competitor: In boxing, the foil receives as much light as the champion.

*Translator’s note: Since this article was published, such photographs have been received and made public.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.