Just days before the United Nations Copenhagen Climate Change Conference, what can we expect of China, the single biggest polluter on the planet? Apparently not much more than meager concessions on carbon emissions reductions, Valerie Niquet explains to Les Echos. Ms. Niquet is the director of the French Institute of International Relations, Asia Division.

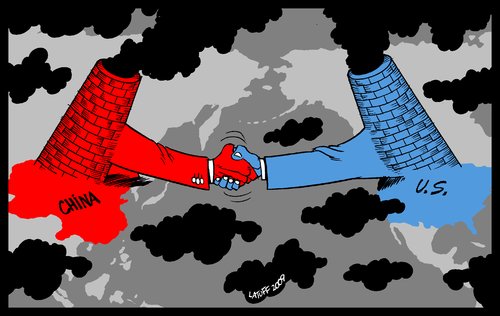

Les Echos: How would you analyze the Chinese announcement of carbon emissions reductions amidst the excitement of the American declaration?

Valerie Niquet: We’re presently seeing a competition between China and the States, each not wanting to appear the lesser in its efforts regarding climate change. This announcement is extremely important in terms of image. It is also rather positive in terms of involvement, although it bears upon reductions in carbon intensity, and not a 45 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, as certain papers have written. This means that China will produce a little less gas per point of Gross National Product. But given Chinese statistics, this translates into a 90 percent increase in greenhouse gases from 2005 to 2020. It seems they’re playing with words and appearance.

L.E.: What we’re hearing isn’t good news, then?

V.N.: The good news is that the Chinese are moving to reduce their carbon concentrations. Until now, they would only talk about reducing their energy consumption – that is to say using less energy per unit of GNP – their objective being to decrease their energy consumption by 20 percent in 2010. They will certainly achieve this, most notably because of the economic crisis. In reality, we’re talking about a prolongation of this trend since, when you minimize the use of energy used to produce one unit of GNP – what the Chinese have been attempting to do for a long time, for cost reasons – you automatically reduce the carbon intensity.

Taking today’s carbon concentrations into account, China is showing that it recognizes the importance of the climate issue. That recognition is important but it is also in correlation with the will of Beijing to position itself on the international scene, particularly alongside the United States. Without talk about it from the outside world, the environment wouldn’t be a central issue within China. However, a number of experts that are close to Chinese authorities have convinced them that China could, at a very small cost or even reaping some considerable financial benefits, buy themselves peace of mind and a positive image on the international scene with a few scarcely committal statements. That’s what we’re seeing being put into place right now. At the moment, though, there won’t be any major changes.

L.E.: Can we hope more for Chinese concessions in Copenhagen? How far could Beijing go?

V.N.: I don’t think that the Chinese authorities will go beyond what they have just proposed in terms of a reduction in emissions. In their mind, negotiations in Copenhagen must now concentrate on what the West is going to do and the attempt to try to draw maximum concessions out of them.

L.E.: In particular, what are the Chinese hoping for from Copenhagen?

V.N.: A massive financial commitment on the West’s part that will facilitate the ‘greening’ of China’s economy with advances in technology. Yet, that will not be proposed, in any case, by the U.S.

L.E.: In what way have environmental concerns shaped international relations, and in particular, Sino-American relations?

V.N.: For China, the environment is one issue among others in relationships of force that have been established with exterior partners. In 2009 and after Obama’s arrival in office, we thought what we were seeing was the institution of a privileged partnership between China, henceforth known as a great world power, and the States- even a kind of ‘G2’. But it seems that, putting emphasis on the importance of American presence in Asia and its other allies in the region, Obama’s China visit didn’t live up to Chinese expectations. Consequently, they seem to have moved from a situation of complicity to something of a rivalry, as we see exemplified by the announcement of Prime Minister Wen Jibao’s presence in Copenhagen the day after the announcement of Obama’s attendance at the summit. This rivalry, though, has ended in a number of deadlocks even before Copenhagen.

L.E.: And with India, can we also speak of a rivalry?

V.N.: India emits much less than China, the biggest polluter on the planet, and is thus subjected to much less pressure concerning its commitments. India’s emissions levels are very low in relation to China and that exempts it from commitment. At present, its position is a lot more radical than China’s. India seems to make fervent demands on the opening of intellectual property rights for green technologies. China, claiming to have already produced some of these technologies, which it has absolutely no intention of sharing for free, has been more prudent. At the end of the day, though, China and India are two leaders in the developing world.

China, however, is trapped by its image as the world’s second biggest economic power. This image is totally disproportional to reality – it takes a mere visit to the Chinese countryside to measure how much the country is still confronted by serious development issues. China upholds the rhetoric of a great power and legitimates its regime with the idea of national pride and a kind of quasi-third world discourse that nobody really buys.

L.E.: Are we seeing a redefinition of international relations around the climate question?

V.N.: I don’t think so. Just before Copenhagen we’re seeing, by contrast, an affirmation of old positions on the part of three groups:

– The new post-modern powers (Japan, E.U.), who are forming an axis at the cutting edge of the issue. It has yet to be seen whether it’s practical or not;

– The classical powers with the U.S. at the forefront who, led by Obama, tend to align themselves with the European position, even if they’re still far behind in terms of internal limits , and are more open than before in multilateral dealings;

– The developing world, with which India is still associated, and China remaining isolated and self-centered.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.